Len Oliver’s series about playing soccer in Philadelphia in the 1940s and 1950s continues with a look at high school and college.

Philadelphia high school soccer

Just as today, high school soccer in Philadelphia in the ‘40s and early ‘50s reflected club soccer. All the public schools and many of the private schools had soccer teams, but the schools in the neighborhoods with ethnic strongholds dominated the high school scene. At Northeast High School, for example, where most of the Lighthouse products went, including Bahr and other pros of the day, we ran the school’s unbeaten string to 96 games, with 63 straight shutouts–a run that lasted over 10 years. City titles, All-Scholastic representatives, All-Star games–all came to the street-smart youngsters who came out of the Lighthouse Boys Club. The annual All-Star match with New York’s high school stars would draw 3,000 spectators, with the teams playing for the Oldtimers’ “Old Shoe” Award. No girls played club soccer, and no high schools had girls teams. We would have to wait 30 years for the high schools to adopt girls’ soccer, when in a different age more and more club players and their parents demanded equality with boys’ soccer, spurred by Title IX of the Higher Education Amendments of 1972.

Soccer was a sport dominated by the club structure. You cannot develop a player in high school, you can only further talents already developed and raise a player’s awareness of the game. This fact was often lost on the media, so accustomed to focusing on high school and college games while ignoring where the real soccer was played. The same holds true today. Our high school games would draw 500 fans, and over 5,000 came out for the City Title Game, usually pitting Northeast against Girard College, a school for orphans known for its soccer talents.

The college game

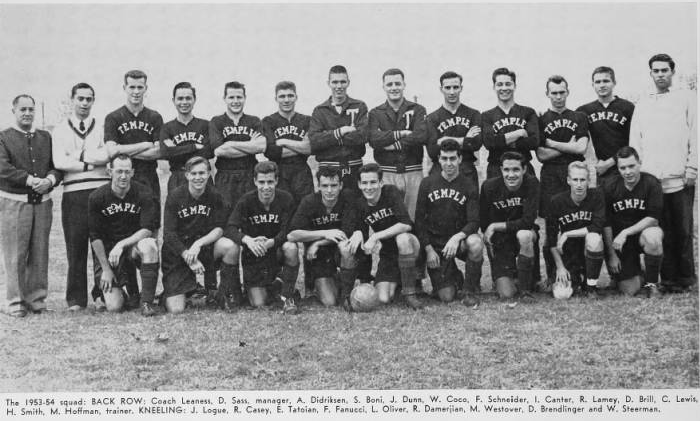

Philadelphia liked its soccer, and the college game reflected the strength of Philadelphia youth soccer. All the local colleges fielded strong teams – Temple, University of Pennsylvania, La Salle, and Drexel leading the way. Many of the Lighthouse-Northeast H.S. contingent received full scholarships to Temple, one of approximately 90 varsity programs around the country in the early ‘50s. The strongest teams, like Temple, the University of San Francisco, Queens College, and Penn State University were fed by the influence of urban youngsters, while in the Ivy League, New England’s prep schools provided the talent. No women’s varsity soccer programs existed.

On New Years Day in 1950, the nation witnessed the first College Soccer Bowl, bringing perennial powers Penn State and USF to St. Louis in a game that ended in a 2-2 tie. The schools were declared Co-Champions. Cross-sectional rivalry had become a reality, giving a great boost to college soccer.

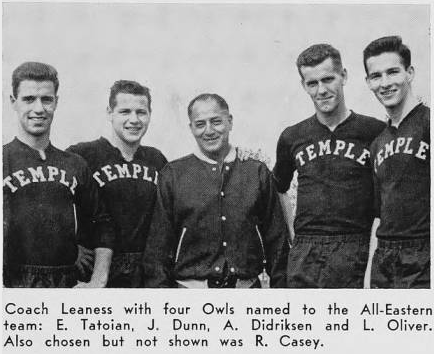

College soccer history was made in 1951 when our Temple Owls met USF in the second Soccer Bowl in San Francisco’s Kezar Stadium before 10,000 fans – then the largest crowd to see a college soccer game in the US. The game attracted outstanding media coverage, accounting for the attendance. We flew cross-country on a 24-hour flight. Coach Pete Leaness asked me to captain the team from my center half position, an honor for a freshman. We defeated USF 2-0 with Ed Tatoian scoring both goals, and Temple was named National Champions. No more Soccer Bowls were held until 1959 when the NCAA began its formal playoff system.

The kids from the streets of Kensington and the playing fields of Lighthouse transferred their skills and competitiveness to college soccer, with Temple losing only three games in the four years I played. Some of the local teams such as Drexel and Penn were very strong, bolstered by the ethnic neighborhood players, but Temple dominated Philadelphia college soccer. We were again declared National Champions in 1953, after an unbeaten season.

During my freshman year at Temple, we played the traditional 2-3-5, but moved in subsequent years to the W-M. We essentially put ourselves on the field, ran the practices, and rarely played less than the full 90 minutes. Each year, we watched as new varsity teams sprang up across the country, so by 1955 when I graduated from Temple there were 125 college soccer programs in 31 states. One year later, there were 171 college teams, with another 100 playing club soccer. The college game was on its way, fueled by American-born youngsters.

During my freshman year at Temple, we played the traditional 2-3-5, but moved in subsequent years to the W-M. We essentially put ourselves on the field, ran the practices, and rarely played less than the full 90 minutes. Each year, we watched as new varsity teams sprang up across the country, so by 1955 when I graduated from Temple there were 125 college soccer programs in 31 states. One year later, there were 171 college teams, with another 100 playing club soccer. The college game was on its way, fueled by American-born youngsters.

The early ‘50s were also a time of experimentation in college soccer. Up to this time, college soccer had followed FIFA’s Laws. In 1951, the colleges introduced the “kick-in” to replace the throw-in, a change benefiting the inferior teams. They essentially received a free kick instead of the normal throw-in, thereby taking a restart tactic out of the college game.

Other experiments, short-lived, included an arc 18 yards out instead of the penalty area. Free substitution was the norm, allowing less skilled but fit “runners” to come in off the bench and affect the game. Colleges also played 22-minute quarters, and referees employed the two-man system, enabling older referees–and there were many–to remain in the game a few years longer. For example, my neighbor and dear friend, Jimmy Walder, refereed high school and college games well into his 80s.

The college referees came basically from the amateur ranks, all former players, who tolerated no abuse, but who let the players play and work out their differences on the field–where they belong. In one memorable, hard-fought game between traditional rivals Temple and Penn State for the National Championship in 1953, play became so heated that one Temple player broke his leg and several others were carted off. The referees, Walder and Harry Rogers, both from Philadelphia, called time and brought both teams to mid-field. “You’re getting our first warning–all of you,” said Walder sternly. “Next time you’re gone.” Players settled down, just as intense, but fair and the teams belted it out in a 2-0 Temple victory without any more trouble.

It was the only time in my career that all 22 players had received what amounted to a “yellow card” in today’s language.

When we left Temple, we finally split up the “Lighthouse connection,” some of us going into the Armed Forces, some to the pros, some back to the amateur leagues, and some coaching. Almost all of us stayed in the game into our 30s, often competing with, and occasionally, against each other.

A version of this article appeared at the Philly Soccer Page on December 31, 2012. The article is excerpted from a longer piece that appeared in 1992 in the Michigan Ethnic Heritage Studies Center‘s Journal of Ethno-Development originally entitled “American Soccer Didn’t Start with Pele: Philadelphia Soccer in the 1940s and 1950s.”

I played on the ’58 team from Girard College that went 13-0 and were declared the Phila. HS Champions by the Inquirer and the Bulletin. Nothing Catholic and Nothest and Frankford were our fiercest rivals. We played several college Freshman teams like Penn, Penn State and Navy. The soccer tradition at Girard was second to none. Teams from ’39 thru ’41 went undefeated and un scored upon. The ’58 team was captained by Bill Killen who went on to become one of the most renowned coaches in America. He was all-American at West Chester.