Frank MacDonald’s series on FC Seattle’s UK tours in the late 1980s continues.

When DeAndre Yedlin’s name was slotted into the Sunderland team sheet earlier this season, it was largely handled as matter-of-fact news by the Makems. The fact that Yedlin is American was more interesting stateside than Wearside.

After all, U.S. internationals Claudio Reyna and Jozy Altidore had already worn the red and white strip. Dozens of other Yanks paved the way for Yedlin. Going back a generation there had been McBride and Dempsey and Hahnemann, before that Moore and Harkes and Friedel, with Kasey Keller breaking ground as Millwall’s first-choice keeper in 1992.

Maybe, just maybe, those once-startling signings were made a bit more palatable for the partisans of Millwall, Fulham, Spurs and Sunderland by preseason visits of an American club virtually unheard-of in the U.S., let alone in Britain.

Unlike any other

When FC Seattle landed in London, they were unlike any U.S. touring club before or since. Lamar Hunt’s Dallas Tornado had globe-trotted to announce the NASL’s existence in the Sixties. Warner Communications cashed in on the worldwide popularity of Pele´ in the Seventies, much like the Galaxy selling Beckham shirts more recently. In the Eighties, the San Jose Earthquakes accompanied George Best on his farewell tour of Britain, and other NASL clubs paid preseason or postseason visits.

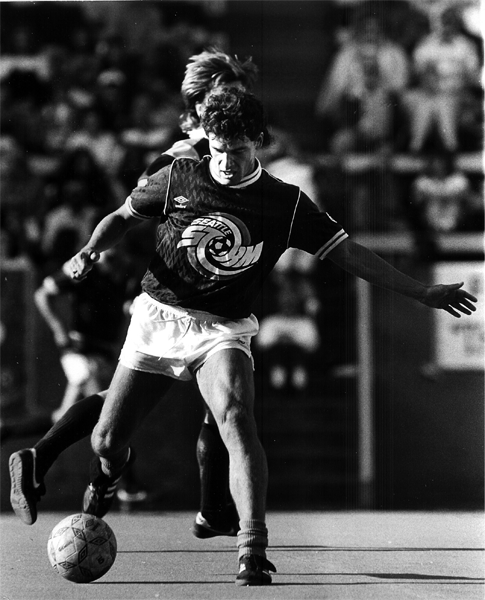

All of the aforementioned were American clubs featuring mostly foreign-born players. FC Seattle Storm’s primary mission was one of enlightenment, both for its primarily homegrown players–as well as the British audience.

“The expectation was to hold our own against some quality opposition, gain some experience and enjoy the thing,” says David Gillett, general manager.

Peter Fewing, then in his third season with FC Seattle, had gotten a taste of what awaited when British clubs came to town. He was effectively clotheslined by a Hearts player, dropping him suddenly to Memorial Stadium’s unforgiving turf.

“I was thinking this was going to be very physical, and we didn’t want to be embarrassed,” Fewing remembers. “We didn’t want to go there and get an 8-0 shellacking.”

A star showcase

A secondary objective was to showcase a Northwest native and emerging USMNT team star.

Tacoma’s Brent Goulet had gone to tiny Warner Pacific College in Portland, where he was soon scoring tons of goals at the NAIA level (108, to be exact). Goulet earned his first U.S. cap while still a junior, and following his senior year was voted MVP of the West Soccer Alliance, where he played for the Portland Timbers.

When Goulet scored for the national team in springtime friendlies against Millonarios and Benfica, coaches and scouts, both at home and abroad, took notice. It was pre-internet, but still there was a Jordan Morris-like buzz. Bournemouth went to the front of the line, but Redknapp wanted to see Goulet for himself.

General manager David Gillett says Goulet and the Storm had a mutual interest: Seattle needed added punch up front while the young phenom was looking for a platform to help promote his cause.

“We helped showcase him, and he generated a lot of interest, both for our club and for him as a player,” contends Gillett. With FC Seattle shorthanded due to some players’ work and personal commitments, coach Tommy Jenkins invited Goulet and fellow Portland forward Scott Benedetti to join the tour. They were retrieved from the airport en route to Middlesbrough, for Seattle’s first match that evening.

Underestimate at your peril

Boro was on the rise under Rioch. They had averted bankruptcy and won promotion to the second division the previous season, and in 1988 would move up again, to the top flight, nowadays known as the Premier League. While Rioch had respect for the Americans’ abilities, his chosen squad was most likely a combination of starters and reserves. They soon would learn to underestimate Seattle at their own peril.

It was still scoreless in the second half when Goulet struck. He had already posed problems for the Boro defense with his speed and quickness. Now he was poised for a free kick a few yards outside the box.

“I didn’t hit it as solid as I wanted, but it curled into the upper corner, tailing away a bit, but it went where I aimed it,” recounts Goulet, 28 years later. “We were ecstatic. But Bruce Rioch, he was upset. Now I understand what kind of pressure they were under. You don’t want to be losing to a bunch of Americans at that time.”

Wrote a local reporter: “Seattle threatened the biggest upset at Ayresome Park since North Korea beat Italy in the 1966 World Cup.”

Jenkins called it an “unbelievable” goal, but there was still 20 minutes remaining.

The crowd of 5,000, once curious, had now grown restless. The manager’s blood was up. Rioch lit into his team and they responded with two late goals to prevail. “We just ran out of steam,” explains Jenkins. “It was a wet, soggy field, and we didn’t have the legs and lost, 2-1. It was no disgrace.”

The offers roll in

By the penultimate match at Dundee, Goulet was being watched by Celtic’s assistant coach, who invited him to Glasgow for further appraisal. Playing with the Celtic reserves at Parkhead, he scored on Motherwell. Manager Billy McNeill was quick to offer a contract, albeit without assurance of a work permit.

After Seattle played QPR, Goulet saw another offer. “They saw me go past their guys and said, ‘Wow, this guy’s fast,’” Goulet recalls, saying he wasn’t particularly fresh, given the games falling every other day.

“I told them how much Bournemouth were offering, and they upped everything, but they couldn’t promise a work permit,” says Goulet. At the time he and his sponsoring club needed to convince the FA he was better than the hundreds of out-of-work British footballers.

Apparently Redknapp and Brian Tiler, the former Timbers coach turned Bournemouth managing director, proved persuasive to the FA, securing the work permit and, in the process, Goulet’s services.

Ahead of their time

As for the rest of the Storm, while they collectively exceeded expectations, earning a draw at QPR and remaining competitive in four losses by a combined 9-2 goal differential. Aside from Goulet, however, no offers of trials or contracts were forthcoming. For them, at least.

“Ideally it would’ve been beautiful to be looked at or picked up by a team,” admits Jeff Koch, goalkeeper. “Really it was our chance to see what we could do against the big boys.

“Had we been four years later, it might have been a little different for some of us,” contends Koch. “We showed that we’re capable enough that they might start taking a look at Americans. We weren’t there yet, (but) I would like to say that we got the ball rolling.”

Three years after Goulet, John Harkes would join Sheffield Wednesday. A key was his UK passport, thanks to his Scottish-born father. Not until five years on, in 1992, did Keller make it to England via a U.S. passport.

“We knew a change would be opening doors for people,” reflects Hamel. “You know when you’re part of something and (that) times are changing. When you’re in that time, you embrace it.”

The series continues next week. A version of this article first appeared at the Frank MacDonald blog on October 9, 2015.

Good stuff.

That Dallas Tornado tour was so oddball that shouldn’t count as a competitor to this one. That team, if I recall correctly ,was composed entirely of British, Dutch and Danish players, none of whom had ever set foot in Texas. It played 31 games on a world tour, mostly in Asia, before it finally landed in America. Not exactly a representative of American soccer.

Pingback: North America: Foreign Players in the Football League - The 1888 Letter