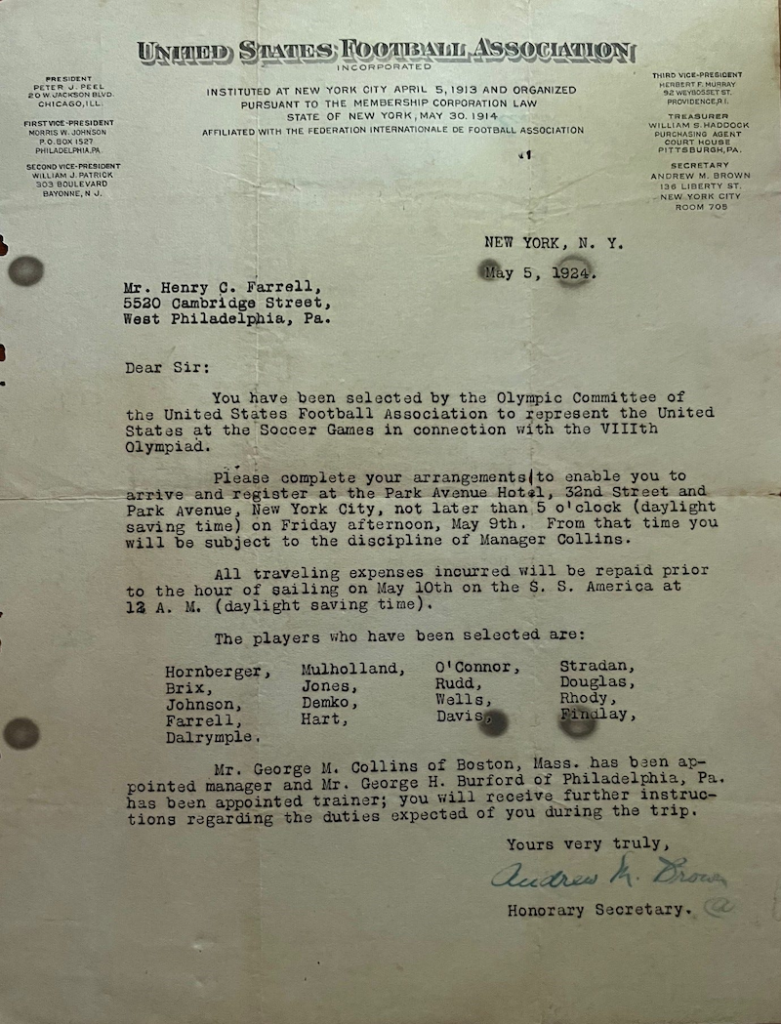

Only a handful of days before the U.S. was to embark for the 1924 Olympics in Paris, France, defender Henry Farrell of Philadelphia and his teammates received a letter from the United States Football Association, congratulating them for making the U.S. Olympic team.

Dated May 5, 1924, here is what the letter to Farrell said:

Dear Sir:

You have been selected by the Olympic Committee of the United States Football Association to represent the United States at the Soccer Games in connection with the VIIIth Olympiad.

Please complete your arrangements to enable you to arrive and register at the Park Avenue Hotel, 32nd Street and Park Avenue, New York City, not later than 5 o’clock (daylight saving time) on Friday afternoon, May 9th. From that time, you will be subject to the discipline of Manager Collins.

All traveling expenses incurred will be repaid prior to the hour of sailing on May 10th on the S.S. America at 12 A.M. (daylight saving time).

The players who have been selected are:

Hornberger, Brix, Johnson, Farrell, Dalrymple, Mulholland, Jones, Demko, Hart, O’Connor, Rudd, Wells, Davis, Stradan, Douglas, Rhody, Findlay

Mr. George M. Collins of Boston, Mass. has been appointed manager and Mr. George H. Burford of Philadelphia, Pa. has been appointed trainer; you will receive further instructions regarding the duties expected of you during the trip.

Yours very truly,

Andrew Brown

Honorary Secretary

(Author’s note: The name of Andy Stradan’s name also was spelled Straden. In modern-day information resources, it is spelled more the latter way).

Putting the band together

While it was difficult to document since there are no surviving members of the team from that era, it is likely the players knew they were selected after trials at a field named quite appropriately, Olympic Park, Patterson, N.J. on Sunday, May 4 at 3 p.m. Twenty players participated in the tryout and as aforementioned, 17 made the team. It was sort of soccer’s version of musical chairs, as three players wound up standing instead of sitting pretty.

Candidates were divided into three groups that played three 30-minute periods with a five-minute break between each one.

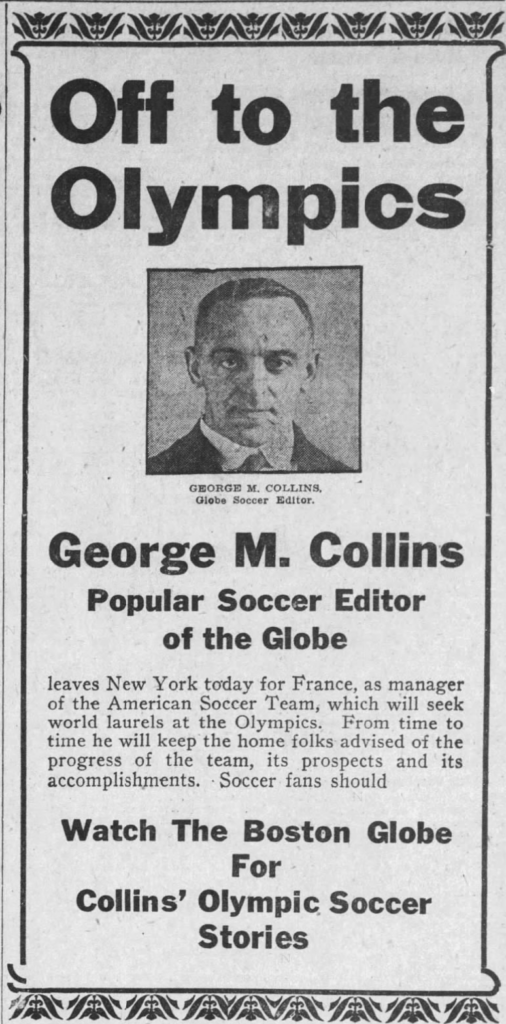

Collins of Boston, the soccer editor of the Boston Daily Globe (from 1914-1950), was named manager and coach, which made for an intriguing conflict of interest, because he reported about the Olympic games for the Globe. There was little doubt Collins was soccer crazy. Once, after breaking his leg, he played under the name of George Mathews so his wife wouldn’t worry about him.

Collins emigrated from Scotland to the U.S. in 1907. At the age of 19, he was secretary of the Massachusetts State Association and was third vice president of the U.S. Football Association. According to the Society of American Soccer History (SASH), he assisted in establishing the National Amateur Cup competition, which kicked off in 1923. He was inducted into the National Soccer Hall of Fame in 1951.

The players who were chosen had less than a week to get their affairs in order before journeying across the Atlantic Ocean to France.

The team was dominated by players from the Philadelphia and New York regions, with others from points west in Pittsburgh, Chicago and even Los Angeles.

The roster by city and region:

Philadelphia (8): Defenders – Irvin Davis (Fairhill FC), Henry Farrell (Fairhill FC), Arthur Rudd (Fleisher Yarn); Midfielders – William Demko (Fleisher Yarn), Raymond Hornberger (Disston A.A.); Forwards – Sam Dalrymple (Disston A.A.), Andy Straden (Fleisher Yarn), Herbert Wells (Fleisher Yarn; Wells hailed from Boston)

Boston (1): Defender – Fred O’Connor (Lynn General Electric)

New York (1): Forward – William Findlay (Galicia FC)

New Jersey (3): Goalkeeper – Jimmy Douglas (Newark Skeeters); Defender – James “Jakes” H. Mulholland (Scott AA); Forward – James Rhody (Erie AA, now Harrison FC)

Pittsburgh (1): Midfielder – Frank Burkhardt “Burke” Jones (Bridgeville FC)

Chicago (1): Midfielder – Carl Johnson (Swedish-American FC)

St. Louis (1): Forward – Edward Hart (St. Matthews F.C.)

Los Angeles (1): Forward – Aage Brix (Los Angeles Athletic Club)

Yes, the team had only one goalkeeper, Douglas, which, in today’s game, would be playing with fire.

The team even had a doctor among its roster of players, Aage Brix of Los Angeles, who served his internship in 1916 in Los Angeles City and County Hospital.

In his dual role as a Globe reporter and U.S. manager, Collins broke the story in the Boston newspaper on Monday, May 5.

The Olympics, soccer (football) or many other sports, was a different animal back then.

Not as many countries and athletes competed because the world, especially developing countries in Africa and Europe, had not yet seen quicker transportation.

The Olympic soccer tournament had been staged in 1908, 1912 and 1920, dominated by European countries. The 1924 competition saw the inclusion of teams from the Americas – the USA and Uruguay and Egypt from northern Africa.

The team did not have to qualify or play many, if any competitive matches, prior to the Olympics.

FIFA was not as domineering or expansive as it is today. And the first World Cup was six years away.

So, in many quarters, the Olympic soccer tournament was considered the world championship.

Well before teams could jet around the world, steam ships were the main modes of transportation for many teams situated across the Atlantic Ocean. That limited the number of teams that could participate in international competitions. And many of the smaller countries did not have teams good enough to qualify or try to compete.

A different world, indeed.

The 1920 fiasco

To truly appreciate that the American soccer team competed at the 1924 Paris Summer Games, we have to go through a brief confusing and confounding history of why the USFA did not send a team to the Antwerp Games in Belgium four years prior.

A major controversy was revealed, according to a story in the New Bedford Sunday Standard of Nov. 7, 1920.

The headline and subheading: “Soccer heads are split over failure to send Olympic team: Former President Manning of U.S. F.A. Declares Officials Merit Deserved Indictment, Reproach and Shame – Declares Secretary Cahill’s Personal Attack Full of Falsehoods”

The lede to the story: “Failure of the United States Football Association to send a soccer team to Antwerp to take part in the Olympiad games has developed a split among two of the leading lights of the National Association. Thomas W. Cahill, honorary secretary, and Dr. G. Randolph Manning, former president of the U.S.F.A, are at war over the subject, the ex-president declaring that the committee and officials of the U.S.F.A.”

In March 1920, Olympic soccer committee selected representatives to travel to Antwerp with the team, according to Collins’ story in the Boston Globe. Cahill, who took the first U.S. men’s national team to the continent to play in Norway and Sweden in 2016, was to be in charge of the players and make arrangements.

According to the story, Cahill claimed there was a poor response for financial assistance from state associations and that it would have been a hard matter to put together a team with a winning chance. Cahill said that only $149 had been received from the various state associations to back the Olympic team. Approximately $10,000 was needed to pay for expenses in France. That would be peanuts today, but costs were different a century ago.

Bottom line: It was a missed opportunity.

So, it was wait another four years.

The voyage

In the days before jet planes as we know it that can whisk us from one continent to another in a matter of hours, American teams needed to take a ship — today, some might call it a slow boat ride to Europe or South America — to get from here to there.

It took 10 days to travel to Cherbourg, France, on the northwest coast of France.

In comparison, today, it takes eight hours, if everything goes right, to fly from New York to Paris.

Earning a spot on the Olympic team was a big deal to many. For example, center halfback Fred O’Connor, was given a sendoff by 500 residents of Lynn, Mass. on May 8. That included a parade, and a dance at the Casino Hall. O’Connor was given a leather traveling bag by Councilor Fred L. Twomey. Similar farewells were duplicated in other towns.

On May 9, the team was given a banquet by the American Olympic Committee (A.O.C.) at the Park Avenue Hotel.

Joined by A.O.C. vice president Col. A. G. Mills, the team the team embarked on the S.S. America from Hoboken, New Jersey on May 10 for the voyage. According to the Boston Globe, “an immense crowd saw the team off at the pier.”

On May 12, the first on-board training session was held under the auspices of trainer George Burford at 7 a.m.

“The men assembled on deck and went through breathing exercises and leg exercises,” Collins wrote in his official report. “This before breakfast. At 10:30, they were given one hour workout on deck.”

The players trained twice a day — morning and afternoon on the ship. The morning session was dominated by calisthenics and gym work, while the afternoon workouts included shooting, heading, trapping and jogging on the top deck.

That also included skipping rope, working with a medicine ball, calisthenics before heading to the gym, where the players worked out on various equipment for 15 minutes.

Mills was impressed with the training.

“He commended the soccer men on the splendid manner in which they went about their training and the manner in which they trained,” Collins wrote in his report.

In one of his notes, Henry Farrell said that defender Arthur Rudd had kicked the ball overboard into the Atlantic.

Oops.

No one tried to retrieve it.

In his personal collection, Farrell had a picture of his teammates shooting craps, although his caption jokingly claimed it was a prayer meeting.

“One of my father’s memories of the Olympics was shooting craps on the boat,” his granddaughter, Sue Beatrice told this writer several years ago, with a laugh. “He made friends there. They gambled and had fun. It was a whole different world for him. He got a kick out of that. He had a lot of photos. I think he called them prayer groups, where they’re all kneeling and they’re actually shooting craps.”

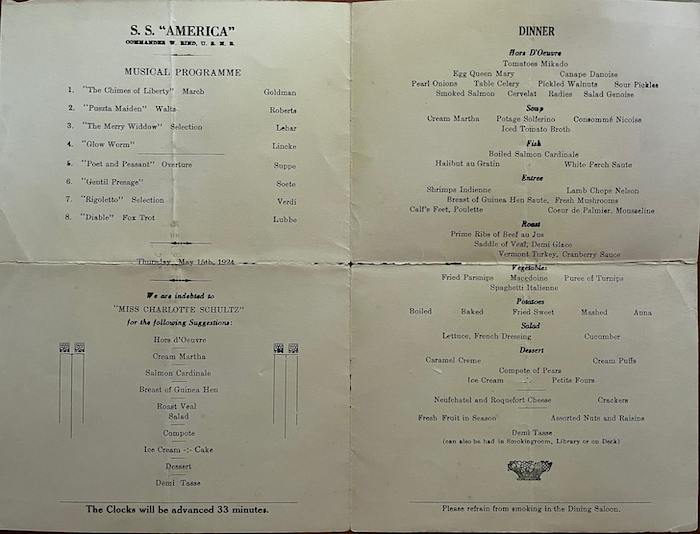

Some food for thought

There was little doubt that the team was well fed.

According to a menu that Farrell brought back home, at one dinner, the team had a choice of:

Hors d’oeuvres

Tomatoes Mikado, Egg Queen Mary, Smoked salmon and salad Genoise), soap (Cream Martha, Potage Solferino, Consommé and ice tomato broth

Fish

Boiled salmon, halibut, white perch

Entrees

Shrimp, lamb chops, breast of Guinea Hen, calf’s feet

Roast

Prime rib au Jus, Veal or Vermont Turkey

Vegetables

Fried parsnip, puree of turnips, spaghetti Italienne

Potatoes

Boiled, baked, fried sweet, mashed or Anna

Salad

Lettuce, French dressing, cucumber

Dessert

Caramel Creme, Cream puffs, compote of pears, ice cream, petite fours, cheese, crackers, fresh fruit in season and assorted nuts and raisons

Land ahoy and a problem or two

The U.S. team disembarked in Cherbourg, France on May 19, “singing, cheering and exuberant,” according to one newspaper account, before venturing to Paris to prepare for its first-round game against Estonia (many newspapers spelled it Esthonia back then) six days later at what is known today as “The Chariots of Fire” Olympics.

The players were hardly in good spirits when they saw their accommodations at the Olympic Village, adjacent to Colombes Stadium. They staged a revolt, claiming the food was unsatisfactory and their living quarters were infested. Arrangements were made to move the team to a hotel about a half hour from the middle of Paris, Sam Foulds and Paul Harris wrote in their book, America’s Soccer Heritage. According to Collins’ report, they found better quarters at the Exelmans Boulevard Hotel.

In his dual role as a newspaper reporter and coach Collins was quite forthright in telling the world of injuries. In his May 19 report to the Globe, he wrote about right half back Jim Rhody, who suffered a knee injury on the journey. Collins was optimistic that Burford would have Rhody in shape for the opener.

Today, teams are known to hide the severity of players’ injuries as much as possible or not be specific on what the injury is. One MLS team, for example, has called leg injuries a lower-body injury. One of the coaches’ lines is that they will have to see how they look in training the next day (when the media isn’t around).

The Americans trained at Colombes Stadium the following morning (May 21) and took a trip to the Eiffel Town in the afternoon. On May 22, Collins and Burford put the team through two practices before venturing to Stade Bergere to watch the French Olympic team defeat West Ham United (England), 2-1.

There was no training held on May 24, the day prior to the team’s Olympic opener.

The information game

Back in the day, well before the internet, information on many, if not all teams, was difficult to obtain.

So, not surprisingly, there was erroneous, misleading and inaccurate info published in newspapers on both sides of the pond.

Cases in point:

* The Minneapolis Star published a one paragraph story of the U.S. team, with the headline, “American Team Favorite in Olympic Soccer Play”:

Paris, May 24 – The American Olympic soccer team, one of the favorites to win the title in the Olympics games, was put through a hard drill yesterday in preparation for the competition. Uruguay also has a strong team and is expected to meet the Yankees in the final of the tournament.

There was no attribution for the story, whether it was a wire service report or someone’s imagination.

The Boston Globe printed an Associated Press story headlined “Fear Americans in Olympic Soccer”:

PARIS, May 22 (By A.P.) – Five hundred association football players, trainers and manager, gathered here for the Olympic competition beginning on Sunday, constitute the largest number ever assembled at the same time in one city in the history of the game.

The teams, representing 22 nations, are composed of 22 men each — 11 regulars and 11 substitute.

(Author’s note: Well, not all the teams. The U.S. had 17 players).

Gabriel Hanot, France’s recognized soccer expert, warns his countrymen “to beware of the Americans,” who he says are likely to repeat the success of the American rugby team.

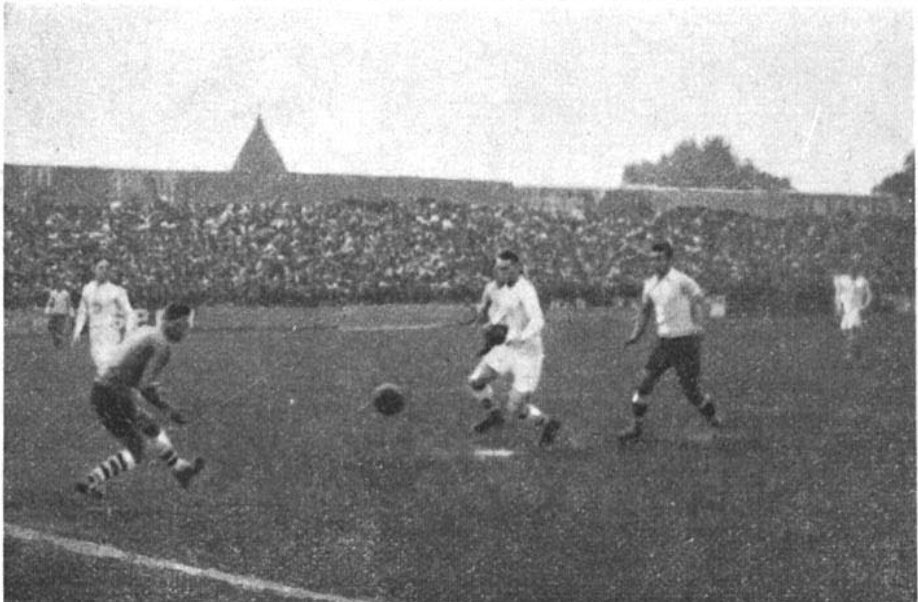

Olympic debut

Unlike today’s four-team groups, that competition was single-elimination. In other words, one loss and you were out. That would be devastating after such a long trip.

So, each team was on the edge. In the May 25 opener against Estonia, the crowd at Pershing Stadium was “somewhat hostile” to the Americans, the Associated Press reported, giving considerable encouragement to their foes. The team was greeted with boos and hisses, the late Sam Foulds, a U.S. Soccer historian, and author Paul Harris wrote.

The USA starting XI: Jimmy Douglas (Newark FC); Irving Davis (Fairhill), Arthur Rudd (Fleisher Yarn), F Jones (Bridgeville FC); Ray Hornberger (Disston FC), Fred O’Connor (Lynn GE), William Findlay (New York Galicia), Dr Aage Brix (Los Angeles AC); Andy Straden (Fleisher Yarn), Henry Farrell (Fairhill), Samuel Dalrymple (Disston FC).

“The game opened with our boys on the attack, but Esthonia soon showed that they were not such slouches as some of the critics thought,” Collins wrote.

“The Esthonian forwards were soon working their way towards our goal but for some clever work by Davis, Rudd and Douglas, might have pierced our defense. … The soccer they played was clever. Stradan got away but hesitated too long and the fine opening was lost. Dalrymple sent in a hot one, but the right fullback got in and cleared. Both goals were being attacked in turn.”

Given that he was a reporter and trying to coach and watch the game at the same time, it was somewhat remarkable that Collins had so many details. Perhaps he was taking notes during the game.

Collins wrote that Brix’s shot hit a post and a penalty kick was awarded to the Estonians for tripping a player in the box.

Andy Straden, who played for Fleisher Yarn of Philadelphia, converted the penalty-kick in the 10th minute past goalkeeper August Lass, for the first goal in USA Olympic history.

About 10 minutes into the second half, Estonia was awarded a penalty kick. Depending on what story you believe. Elmar Kaljot either hit the post or booted his spot kick over the crossbar. The referee claimed Kaljot kicked the ball before the whistle, so he was allowed to retake it. His second attempt hit the crossbar.

Douglas. according to Collins pounced “on it like a cat [and] sent it clear.”

“Estonia continued to press but there were no holes in our defense,” wrote Collins, whose team registered a 1-0 win, the first Olympic victory in U.S. history.

“It was nip and tuck all the way and Esthonia had the better of the game when it came to the fine points, but they could not beat Douglas, who was playing a wonderful game,” Collins wrote in his report.

Collins also spoke to the media afterwards.

“It is a fallacy to say that a winning match is always a well-played match,” he was quoted by AP. “I am not quite satisfied with the showing of our boys, but we will put in some hard licks between now and the second round. If, as we hope, Uruguay defeated Yugoslavia tomorrow, and we were drawn against them, we will try and make it interesting for our South American brothers.”

According to a United Press story, critics said that the USA “had nothing but speed and size.”

“They pointed out that the soccer team was much like the champion rugby player in that the players did not have the fine points of the game, but that they could outlast all the other teams,” the story said.

Taking on some legends

Well, be careful what you wish for because the Uruguayans rolled to a 7-0 triumph over Yugoslavia in their first-round match. Uruguay was at the cusp of its golden age in which they won back-to-back Olympic soccer gold medals (1924 and 1928) and the first World Cup in 1930. Few international soccer experts realized how good this team was and how many players would become legends.

The walking-wounded Americans were forced to replace Brix and Rudd. Farrell also was hurting but played anyway. It was not known who had what ailment, although one Paris newspaper reported players had wrenched shoulders, sprained ankles and sore legs.

The USA never had a chance as Uruguay made a hero out of goalkeeper Jimmy Douglas, who made several vital saves in a 3-0 result. Douglas, starting an American tradition of top-flight keepers, was later selected for the 1928 Olympic team and for the U.S. national side that participated in that inaugural World Cup in Montevideo, Uruguay in 1930. Pedro Petrone scored twice, and Hector Scarone added another.

“Uruguay deserved victory and won largely through miraculous teamwork,” Collins was quoted by the Philadelphia Evening Bulletin.

Collins added in his report: “Our team did our best, but the all-round ability of the Uruguay players, their wonderful combination and control of the ball and play at all times clearly demonstrated that they were past masters of the art of soccer football.”

Even a century ago, U.S. athletic officials realized some of the challenges that faced the team.

“It is easy to understand why Uruguay won,” A.O.C. member Peter Peel told the Evening Bulletin. “In our sense of the word, the Uruguayans are not amateurs, but professionals. They have played together for years and represented their country in many pervious contests. On the other hand, our team scarcely knew each other at all before the present games.”

Unfortunately, that latter scenario began an unwanted U.S. national team tradition that lasted until several decades until the seventies and eighties.

One bit of interesting information: the Casper Star-Tribune, in its May 29 edition, published a one paragraph update of the game at halftime, saying that Uruguay was leading the USA, 3-0.

A couple of friendly encounters

With their return trip not scheduled until late June, the Americans took advantage of their time in Europe by playing friendlies. They defeated Poland, 3-2, in Warsaw on June 10 and lost, 3-1, to an Irish Free State team in Dublin on June 16.

News of those two friendlies certainly traveled slowly in those days. Collins’ report by mail did not appear until the July 5 edition of the Globe.

“They were fully entitled to their win, as they were far the better team,” he wrote of the Irish Free State team in the Globe, having the first and last words on the result. “Traveling at express rate from Warsaw did not help our players any, as they appeared to be weary after the first 15 minutes.”

The US team started its journey home on the steamer George Washington on June 21.

“Traveling through 10 countries in eight days, playing two international games and breaking even is not so bad,” Collins wrote. “It would have been nice to win them both. But when you meet a better team, and get licked, there is no excuse to offer.”

It is nice when a coach can be brutally honest, especially when he can control what is said in the media.

The game in Dublin was only the sixth official international match for the U.S. team, which had a 3-2-1 record.

That Olympic triumph, however, was truly special.

How special?

Let’s put that win into proper context.

Incredible as it may sound, it would take 60 years and eight Olympic soccer tournament participations before the U.S. would win another game in the competition with a 3-0 victory over Costa Rica in Palo Alto, Calif. on July 29, 1984.

But that, as they say, is another story for another time.

A version of this article first appeared on Michael’s View from the Front Row Substack on July 23, 2024.