In December 1894, the New York Sun reported “association football will take a boom within the next few days” as “several well-known clubs have decided to organize a league, which will be known as the New York State Association Football League.”[1] Echoing the enthusiastic claims of many failed endeavors, the New York Sun reported “the projectors have every assurance that the new league will be successful, and firmly believe by improving and introducing new plays that the pastime will become popular.” Clubs showing interest in the new league included the Centreville AC of Bayonne, New Jersey; Red Stars of Harlem, New York; Scottish-American AC of Newark, New Jersey; Wanderers of South Brooklyn, New York; and the West Side Shamrocks. Prospective members included Americus AA; Unions of Kearny, New Jersey; Sylva AC; and New Rochelle FC of New Rochelle, New York.

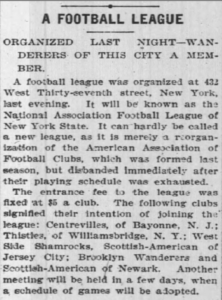

The meeting, chaired by Whitworth Southern of the recently organized Brooklyn Wanderers, was held on December 14, 1894, at Cleary’s, the establishment of ex-West Side Shamrock captain Joseph Cleary, on 432 West Thirty-Seventh Street, New York. Much of the December 14 meeting focused on various grievances harbored between local clubs and the “unruly playing which characterized the games last year.” The New York Sun reported:

The first business done was to agree on a name for the new organization. It was at first suggested that the old body which flourished last year, the American Association [Football League, the AAFL], be revived. This occasioned considerable dissent. At length, it was decided to call it the National Association Football League. The entrance fee was fixed at $5. Of course, the projectors figure on having over a dozen clubs to join the league.[2]

Like the AAFL, a silver cup valued at $50 would be awarded to, and become the absolute property of, the winner of the NAFL’s first season. It was also agreed that another trophy would be “donated for the ensuing season.”[3] If treasury funds permitted, the winners would also receive gold medals, with silver medals going to the runners-up.

The representatives of six clubs were present at the first meeting: Graham Winters of Centreville AC; J. McGill of the Williamsbridge Thistles of Williamsbridge, New York; H. Johnstone of the West Side Shamrocks; J. J. Barnes of the Scottish-American FC of Jersey City, New Jersey; Whitworth Southern of Brooklyn Wanderers; and Robert Johnson or J. Kelly of the Newark Scottish-American FC. Plans called for a closed league model, for every club to have enclosed grounds, and for the league to adopt a Sunday and holiday schedule. Newspapers as far away as Chicago reported on the meeting, with the Chicago Tribune among the many papers calling the new league “merely a reorganization of the American Association of Football Clubs which was formed last season.”[4] The Tribune was not too far off the mark, as most AAFL stars would end up on future NAFL rosters.

The election of league officials and adoption of a schedule was postponed to a future meeting, scheduled for January 5, 1895. Southern told the New York Sun in late December that the league “will be launched on a sound business basis” and that “all the clubs that play the Association game have expressed a desire” to join the league.[5] New clubs expressing interest included Rangers of Bayonne, New Jersey; Varuna Boat Club of Brooklyn, New York; and Madisons of Harlem, New York.

Southern also hoped to address the question of official umpires and linesmen, which was such a problem during the days of the AAFL. The location of the meeting — at Cleary’s on 432 West Thirty-Seventh Street — was also a point of contention, with several prospective members complaining of the site’s location and inadequate size. Perhaps this was a backlash against Cleary, whose Shamrocks ruffled more than a few feathers during the AAFL days. Southern, committed to harmony, agreed to host future meetings at a different location.

There is no evidence that the January 5 meeting ever took place. Possibly owing to the attempts by Southern to organize the league during the busy holiday season, the New York Sun reported: “the previous meetings of the association have not panned out as promising as the projectors of the league anticipated, owing to the tardiness of the various clubs playing Association football in not having representatives on hand.” Southern told the Sun that a hard deadline of Tuesday, January 8 would be enforced for clubs wishing to join the league and that the league “had the support” of twelve of the leading clubs in the New York/New Jersey Region: Americus AA; Centreville AC; New Rochelle FC; Red Stars; Jefferson FC of Newark, New Jersey; Greenville AC of Greenville, New Jersey (part of Jersey City); Union League FC of New York; Williamsbridge Thistles; West Side Shamrocks; Scottish-American FC of Jersey City; Brooklyn Wanderers; and Scottish-American FC of Newark. Southern stated that games would commence in “about a fortnight” with Southern’s Brooklyn Wanderers “ready to set the ball rolling.”[6]

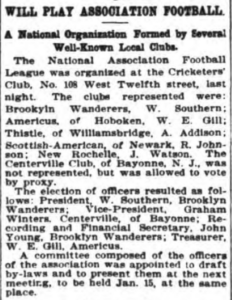

The January 8 meeting proved more fruitful, with several New York newspapers announcing the formal organization of the league. Southern made good on his promise to change the meeting location, abandoning Cleary’s in favor of the New York headquarters of the Cricketers’ Club on 108 West Twelfth Street, near Sixth Avenue. However, even with an extension of the deadline for league membership, only five clubs and their representatives were present: Brooklyn Wanderers, Whitworth Southern; Americus AA, W. E. Gill; Williamsbridge Thistles, A. Addison; Scottish-American FC of Newark, R. Johnson; and the New Rochelle FC, K. Watson. A sixth club, Centreville AC, was allowed to vote by proxy as their representatives could not be in attendance. Far from the dozen clubs pledging earlier support for the league, Southern continued to push for additional members in the coming weeks.

The New Rochelle Pioneer had a more pessimistic view of the proceedings, calling the meeting “disappointing.” Far from being enthusiastic participants, the Pioneer revealed that the Williamsbridge Thistles were “undecided about joining.” The representative of the Newark Scottish-American FC shocked the meeting by declaring that he “had no authority to enter his team.” Finally, the representative from the New Rochelle Club “put a damper on the meeting by stating that the only way in which his club could join the league would be by allowing them to play their games on Saturday.” This revelation should not have been surprising since New Rochelle had “conscientious objections to Sunday football” dating from their organization as a club in August of 1890.[7] Saturday football for the NAFL, however, was impossible “as the players on the other clubs in the league work through the week and could not under any circumstance play on Saturday.” [8] Clearly, Southern had more work to do.

The meeting did, however, accomplish a major goal: the election of officers. As expected, acting Secretary Whitworth Southern of the Brooklyn Wanderers was elected as the first President of the NAFL. Graham Winters of Centreville AC was elected Vice President, John Young of the Brooklyn Wanderers was elected Recording and Financial Secretary, and W.E. Gill of the Americus AA was elected Treasurer. Concluding business for the evening, a “committee composed of the officers of the association was appointed to draft by-laws and to present them at the next meeting, to be held Jan. 15, at the same place.”[9]

Newspaper accounts reflect a desire on behalf of Southern to field an eight-team league, although he extended invitations to thirteen clubs.[10] As only six clubs showed various levels of commitment during the prior meeting, Southern again extended the acceptance deadline to the January 15 meeting date, stating the “league intends drawing up the schedule, so this will be the last opportunity for clubs to become members.”[11] The Brooklyn Daily Eagle reported that Southern “had heard from the Paterson Rangers and the Jeffersons of Newark, regretting their inability to join” and that the “Williamsbridge Thistles had not been heard from, and, as they had not qualified, they were not considered.”[12] The New York Metropolitan soccer community was not as receptive to the new league as previously anticipated. League officials had no idea the entire east coast soccer scene was slowly heading into a downturn that would plague the NAFL and eventually cause the NAFL and AFA to cease operations until 1906.

As planned, the first business of the January 15th meeting addressed the adoption of by-laws drafted by the officers of the association. The New York Daily Tribune recounted several highlights of the meeting:

It was decided that two points should be allowed for a win and one for a draw in deciding the championship, and that the winning club will get a silver cup, which will become its absolute property. The team of the winning cup will also receive gold medals, and the team which finishes second will get silver medals.[13]

Perhaps more important than enumerating the spoils of victory, the NAFL officers gave the referee full power and authority to enforce the laws of the game as well as other matters such as field conditions. The “his decision is final, even if he makes a mistake” approach was no doubt a reaction to the circus atmosphere present at numerous prior AAFL meetings, where numerous protests, mostly due to referee decisions, were argued at great length.

Whitworth Southern, man of mystery

Curiously, NAFL president Whitworth Southern was not a common name in eastern Association Football circles in the early 1890s. While the Amateur Athlete magazine said Southern “has done more for the game than anyone in this vicinity,” he is largely a ghost until his involvement with the NAFL. [14] Even the first and last names used to identify Whitworth in American sporting circles turn out to be incorrect.

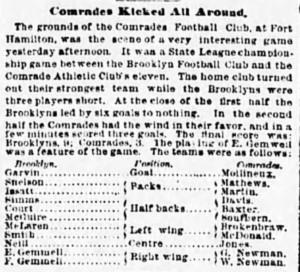

Newspaper accounts show a “W. Southern” playing for football clubs in the greater-Brooklyn area, including the Comrades club of Fort Hamilton, as far back as 1891. He also served an administrative role as secretary of the Comrades, a team referred to by the New York Sun as being “composed chiefly of English players.”[15] Southern then moved to Brooklyn Wanderers, where he was announced as manager on October 2, 1894. As manager, Southern acted quickly to provide the enclosed grounds required for future NAFL play, with the New York Sun reporting on November 22 that the “Brooklyn Wanderers expect to have their new enclosed grounds ready for playing by Dec. 10, or at the very latest, Dec. 17.”[16]

To complicate matters, early 1890’s Brooklyn city directories show a Whitmore (Whittemore) Southern, occupation tinsmith, at the 57th Street and 5th Avenue address Whitworth Southern used to solicit games for the Wanderers in local papers. Ancestry.com searches corroborate the existence of a Whitmore Earnest Southern, also a tinsmith, who emigrated to the United States from Shropshire, England, in August 1885 on the Britannic. This essay assumes that Whitworth and Whitmore are indeed the same individual.

Correspondence with Ruth Dudley, a distant relative of Whitmore’s living in England, reveals the Southern family was “from Shropshire, a large county which borders North Wales to the West and Staffordshire to the North East”.[17] Whitmore moved to the Aston area of South Birmingham around 1878, where at age 14 he “starts working for the Great Western Railway as a ‘lad clerk’ at one of the stations in Birmingham.”[18] He resigned shortly afterward and started an apprenticeship as a tinsmith, the occupation he would continue during his time in the United States. Dudley noted that Whitmore’s “sister Fanny’s family were historically strong followers of the Aston Villa Football Club in Birmingham.”[19] Perhaps Whitmore was an Aston Villa supporter as well. The Villans sported a maroon and white kit from 1880 to 1882, during Whitmore’s time in the city. It may be no coincidence that the Brooklyn Wanderers sported the same color combination in the early days of the NAFL.[20]

New York newspapers at the time also mention a “W. Sothern” who was an influential member of the Acorn Athletic Association, one of the largest associations of its kind in New York. The association held boxing tournaments, large track and field events, and was known to have a world-champion tug-of-war team. The Acorn AA was organized on October 22, 1888, in Bay Ridge Brooklyn, only ten blocks from the address Whitworth Southern used to solicit games in local papers. “Sothern” was associated with the Acorn AA association football team and was the team delegate to the AAFL, as well as acting on the AAFL Executive Committee. The connections are strong, however, additional research is required to determine if “W. Sothern” is indeed our Whitworth (Whitmore) Southern. For the sake of clarity, this essay will continue to refer to Southern as Whitworth even though it appears that Whitmore was his true name.

A schedule is adopted

The main goals of an ambitious league meeting on January 29, 1895 were to formulate the match schedule and adopt a constitution and by-laws. The constitution and by-laws consumed the bulk of the meeting, with the New York Sun reporting that all the delegates appeared “anxious for a thorough discussion of even the most trivial points. Article 12, which gives the referee power to finally decide all points of play and as to the fitness of the ground for play, was argued over for almost an hour before being agreed to.”[21]

The following schedule was adopted, according to the Brooklyn Daily Eagle, “without argument” :

| Date | Game | Location |

|---|---|---|

| March 3, 1895 | Scottish-Americans vs. Americus

Brooklyn Wanderers vs. Centreville AC |

Newark, NJ

South Brooklyn, NY |

| March 10, 1895 | New Rochelle vs. Scottish-Americans

Americus vs. Brooklyn Wanderers |

Ground open

West Hoboken, NJ |

| March 17, 1895 | Centreville AC vs. New Rochelle

Brooklyn Wanderers vs. Scottish-Americans |

Bayonne, NJ

South Brooklyn, NY |

| March 24, 1895 | Americus vs. Centreville AC

New Rochelle vs. Brooklyn Wanderers |

West Hoboken, NJ

Ground open |

| March 31, 1895 | Scottish-Americans vs. Centreville AC

New Rochelle vs. Americus |

Newark, NJ

Ground open |

| April 7, 1895 | Centreville AC vs. Brooklyn Wanderers

Americus vs. Scottish-Americans |

South Brooklyn, NY

West Hoboken, NJ |

| April 14, 1895 | Scottish-Americans vs. New Rochelle

Brooklyn Wanderers vs. Americus |

Newark, NJ

South Brooklyn, NY |

| April 21, 1895 | New Rochelle vs. Centreville AC

Scottish-Americans vs. Brooklyn Wanderers |

Ground open

Newark, NJ |

| April 28, 1895 | Centreville AC vs. Americus

Brooklyn Wanderers vs. New Rochelle |

Bayonne, NJ

South Brooklyn, NY |

| May 5, 1895 | Centreville AC vs. Scottish-Americans

Americus vs. New Rochelle |

Bayonne, NJ

West Hoboken, NJ |

View more on the NAFL first season schedule

League officials created an eight-game schedule for each team, with each team playing the other league members both home and away. The imbalance created by a five-team league necessitated that one team be idle each week. Issues still existed around the New Rochelle club, as they still flirted with admission while continuing to object to playing Sunday football. The remaining clubs were open to reworking the schedule to accommodate them, but it was unclear what grounds the New Rochelle team would secure once any accommodations were made. These issues caused the date for opening games to be pushed back to March instead of the mid-February date originally planned.[22]

The Brooklyn Daily Eagle ran a column on the Wanderer’s participation in the new league and provided, yet again, a primer on the rules and details of association football. However, this account added more artistic license, vim, and vigor than similar accounts:

Nobody who hasn’t seen a good game can appreciate the feverish excitement and the lusty enthusiasm that are provoked over the tricks of a skillful forward as he dexterously dribbles the ball through his opponent’s lines, swiftly, with the leather almost clinging to his feet, dodging this way and that, till within shooting distance of the goal and then – smash! Off it goes like a shot from a cannon’s mouth, low, swift and deadly, fair between the sticks. This individual play is one of the prettiest features of the game, when it is clever, but in a contest between two first class, evenly matched clubs, it is the passing game that is the most dangerous and effective.

However, when referring to New York City soccer in the 1890s, the Eagle was quick to remind the reader of the unfortunate truth that violence, bad behavior, and injuries were a major part of the game:

There are no delays to resuscitate dead men. If a player is injured so badly that he cannot continue he simply leaves the field and the remaining ten men fight the battle out in their crippled condition as best they can. No substitute is allowed after the game has begun, no matter how badly the ranks of a team may be depleted by injuries, nor how many may be ordered off the ground by the referee for violation of the rules.[23]

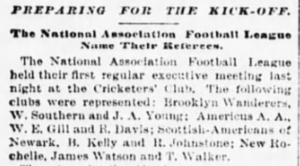

Meeting again at the Cricketers’ Club on 108 West Twelfth Street, the February 12 meeting focused on business “made necessary by the close proximity of the opening of the season, which will be on March 3.”[24] The main topics of discussion included rules for team rostering, the question of acceptance of players who previously played in the professional ALPF, and the release of an approved list of referees. All teams were represented at the meeting except the Centreville AC, a monumental feat considering the occurrence of a snowstorm on February 8 – called “the worst storm since the blizzard of 1888” by the Paterson Daily Guardian — that essentially crippled transportation in the region for days.[25]

NAFL delegates discussed player registration at great length and finally enacted a rule where “all those who participate in championship games scheduled shall be registered fourteen days before they can play.” Keeping the focus on personnel issues, the delegate from the Americus AA (W. E. Gill or R. Davis) raised the “question of debarring the men who took part in the games of the defunct National Association of Professional Football Clubs.” The National Association of Professional Football Clubs, better known as the American League of Professional Football Players (ALPF), was the professional league that folded in October 1894. Players who took part in this league, as well as in the American Association of Professional Football (AAPF), found it difficult to rejoin amateur clubs after the collapse due to their professional status. The question was fully discussed by the meeting delegates “and it was finally agreed not to take action to prevent them from playing, so that they can become members of the league clubs.” Addressing the professional/amateur issue more directly, the league stated that “no player, however, will be allowed to receive remuneration in any manner for playing, outside of traveling expenses.”

It is interesting to note that the delegates did not mention the pool of professional players who signed forms with teams in the AAPF. As the AAPF proposed a spring season to run from the end of March through the beginning of June 1895, the demise of the AAPF may not have been assured at the time the NAFL was in its fledgling stages. The AAPF contained teams from Newark (the Union Athletic Club of Kearny) and Paterson (the “Paterson League” team), two future strongholds of the NAFL. However, the perilous state of the AAPF may have been the reason why no Paterson or Newark/Kearny clubs, other than the Scottish-Americans, were initial NAFL members, the Kearney Unions coming close – named as “interested parties” in the December 10, 1894, New York Sun article.

Perhaps the most important accomplishment of the meeting was the establishment of an approved list of referees to officiate all league games. This list consisted of members from each club (minus Centreville AC), with most of the members being delegates elected to represent their organization at NAFL meetings. This pool of approved referees was a step in the right direction, but the group was still not an independent body immune from partisan accusations. As was commonplace at the time, the two linesmen for each game consisted of a representative from each of the competing teams. Referees were selected for the opening games on March 3, with the Scottish-Americans and Americus AA game at Newark given to James Conners of New Rochelle, and the Brooklyn Wanderers and Centreville AC game at South Brooklyn entrusted to P. Hughes of the Scottish-Americans (later changed to T. Walker of New Rochelle).

The final business of the February 12 meeting was an agreement to not adopt the “penalty kick rule.” Introduced by the Scottish FA, English FA, and Irish FA in 1891, the penalty kick had yet to make its way into mainstream American soccer. One of the influencing factors that convinced the Scottish FA to adopt the penalty kick was an incident that occurred on December 20, 1890, in the Scottish Cup quarter-final between East Stirlingshire and Heart of Midlothian. James Adams, a Hearts defender, saved a goal by fisting the ball out from under the bar, causing a considerable commotion among those in attendance.[26] The incident was one of several that occurred in the UK at the time and the act was becoming more commonplace. As the previous punishment consisted of a free kick where the foul took place, few goals resulted from the infringement, convincing the three Football Associations that something more was required. Interestingly, Adams emigrated to America, became associated with the Newark NJ Football Club and Kearny High School, and went on to be an instrumental force in re-establishing the NAFL in 1906 after a seven-year hiatus. The NAFL later amended its by-laws and adopted the penalty kick in November of 1895.[27]

First game in sight, how did they get there?

With the planning complete, the NAFL was on the verge of its first games, scheduled to commence on Sunday, March 3, 1895. The New York Daily Tribune previewed the fixtures and predicted:

The chief game of the day should result from the meeting of the Brooklyn Wanderers with the Centreville Athletic Club, which will be played on the grounds of the Varuna Boat club at South Brooklyn. These teams are supposed to be the strongest in the league, and it is thought that they are almost evenly matched.[28]

The Wanderers and Centreville AC had met twice during the past season — with each team securing one victory — so a close, competitive game was easy to predict. Thomas Walker, a well-known player from New Rochelle FC, was picked to officiate the game, scheduled for a 2:30 pm kickoff.[29] The second match featured Americus AA against Newark Scottish-Americans at Newark, NJ. The newspapers gave the advantage to the Americus club but noted “the Scots feel confident in their ability to make it interesting for them.” James Conners of New Rochelle was appointed referee.

From a historical perspective, the initial version of the NAFL existed for five turbulent seasons before external circumstances, and those of its own making, caused it to cease operations until 1906. However, compared to other soccer leagues in this region during the same time frame, five consecutive seasons was an eternity. How did the league find success in the face of an extended period of economic depression, labor unrest, and reduced immigration? What did the league do in its planning stages to avoid the pitfalls that caused other leagues to fold so quickly?

- Commitment to Sunday Football – Contrary to leagues such as the ALPF, the NAFL knew its “base,” namely factory hands of Scotch or English birth. This demographic could not support Saturday football due to work commitments. Interestingly, Sunday football would have its problems in coming years due to challenges from local “blue laws.”

- Good League Management – The New York Times commended the selection of league officers, writing:

The league has been particularly fortunate in the selection of officers, for all the men are not alone enthusiastic in their support of the game and willing to do all in their power for the success of the league, but they are men of brains, and competent to fill their respective offices. John A. Young of the Brooklyn Wanderers is proving an ideal Secretary, and his nomination for this important position was a good step in the right direction, which was followed by the election of W. E. Gill as Treasurer and W. Southern as President. Everything points to the success of the organization…[30]

- Committed to business success – Most of the teams entered in the inaugural season of the NAFL were solid, established clubs. Referencing Gill’s Manifesto, experience shows a league cannot be successful if clubs withdraw mid-season (reference the AAFL with the mid-season withdrawals of the Empire and Acorn AA clubs) or cannot field teams to meet league commitments. The public failure of the ALPF also provided an example not to follow. Going into the first week of play, only the New Rochelle club lacked immediate stability due to their insistence on a Saturday schedule.

- Airing past grievances – Most of the clubs considering NAFL play during the planning stages were quite familiar with each other from friendly competitions or leagues such as the AAFL and NYSFL. Prior AAFL meeting reports documented considerable bad blood between delegates and clubs due to referee decisions and/or actions on the field such as fisticuffs. Simple as this may sound, the airing of past grievances may have mended fences and/or discouraged the participation of clubs that could not see past those grievances.

- Solid Constitution and By-Laws – The Constitution and By-Laws were developed by a committee and discussed/tweaked at great lengths during league meetings. Laws concerning player registration were clearly defined.

- Thoughtful Selection and Approval of Referees – The powers given to referees were broad and far-reaching. For example, in the AAPF the home team was the sole judge if a field was deemed playable, while in the NAFL this decision was solely up to the referee. Although still not an independent body, the referees for league contests were chosen in advance and approved at league meetings.

- Prevention of Rough and Violent Play – An important part of the referees’ broad powers dealt with the absolute authority to remove an overly aggressive player from the field at once. These powers would certainly be tested in the games to follow.

Although the future may have looked promising, several issues must have concerned Southern and the other league officers:

- Low Team Turnout – Far from the eight to twelve teams originally envisioned for the league, only five teams were on board at the start of league action. One of the five teams, the New Rochelle FC, was still pushing for a Saturday game schedule.

- Lack of Premier Teams – In its later years, the NAFL would include the top New Jersey clubs and most of the top clubs from New York. In its inaugural season, the NAFL lacked many of the big-name, established clubs from the Kearny/Newark/Paterson region that were staples of the AFA Cup competition, such as the Paterson True Blues and the Newark Caledonians. Many players from these teams, however, would make appearances on NAFL teams.

Notes

[1] “A New Association Football League,” The New York Sun, December 10, 1894, 8.

[2] “Association Football Men,” The New York Sun, December 15, 1894, 9.

[3] “Association Football Men,” 9.

[4] “Association Football League,” Chicago Tribune, December 15, 1894, 3.

[5] “The New Association Football League,” The New York Sun, December 27, 1894, 8.

[6] “The National Association Football League’s Next Meeting,” New York Sun, January 6, 1895, 8.

[7] “Association Football,” The Brooklyn Citizen, January 20, 1891, 3, “The New Rochelle Football Club,” The New York Sun, August 25, 1890, 3

[8] “Association Football Men Meet,” New Rochelle Pioneer, Saturday, January 12, 1895, 8.

[9] “Association Football League Organized Last Night – Officers Elected,” The Brooklyn Daily Standard Union, January 9, 1895, 98.

[10] “Association Foot Ball League,” Brooklyn Daily Eagle, Wednesday, January 16, 1895, 9.

[11] “Sporting Miscellany,” The World, Tuesday, January 15, 1895, 6.

[12] ”Association Foot Ball League,” The Brooklyn Daily Eagle, January 16, 1895, 9.

[13] “National Association Football League,” New York Daily Tribune, January 16, 1895, 5.

[14] ”Association Football,” The Amateur Athlete, October 1, 1896, 7.

[15] “Dribblings,” The New York Sun, February, 2, 1891, 6.

[16] “Football Notes,” The New York Sun, November 22, 1894, 4.

[17] Ruth Dudley, Ancestry messages to Kurt Rausch, November 14, 2023 and November 15, 2023.

[18] Dudley, Ancestry message, November 14, 2023.

[19] Dudley, Ancestry message, November 14, 2023.

[20] “Orton Wins From Conneff,” New York Evening World (Night Edition), May 30, 1895, 1.

[21] “The Schedule of the National Association Football Club,” The New York Sun, Wednesday, January 30, 1895, 8. The constitution of an organization contains the fundamental principles which govern its operation. The bylaws establish the specific rules of guidance by which the group is to function. For a good example look at Spalding Guide 1904-05 for the Constitution and By-laws for the Metropolitan Football League.

[22] “General Sporting Notes,” The Brooklyn Daily Eagle, Tuesday, January 29, 1895, 4.

[23] “Brooklyn Wanderers In It,” The Brooklyn Daily Eagle, Thursday, January 31, 1895, 4.

[24] “Preparing for the Kickoff,” The New York Sun, Wednesday, February 13, 1895, 8. The following list of referees was approved at the February 12 meeting: William Higgins, J. Bissett, W. O’Donnell, P. Hughes, Roderick McDonald, and James Hood, Scottish-Americans; T. Bright and F. Davis, Americus AA; T. Walker, James Conners, and J. Young, New Rochelle; and W. Newman and J. Parker, Brooklyn Wanderers.

[25] “New Jersey Blockaded,” Paterson Daily Guardian, Saturday, February 9, 1895, 1.

[26] “History,” The Heart of Midlothian Football Club, www.heartsfc.co.uk/more/club/history-2. Accessed 21 June, 2021.

[27] “Under Association Rules,” New York Sun, November 25, 1895, 8.

[28] “In The Field Of Sports,” The New York Daily Tribune, Wednesday, February 27, 1895, 10.

[29] “Association Football,” New York Evening World, February 26, 1895.

[30] “Association Football League,” The New York Times, Tuesday, January 29, 1895, 6.