A version of this article first appeared in HOWLER, Volume III (Summer 2013).

U.S. Soccer was 100 years old in 2013, and as part of the three-day celebration in New York City, officials and former players rang the closing bell at the New York Stock Exchange. Many people don’t know soccer in the United States was that old. (Some say she doesn’t look a day over 80.) A deeper dig in the archives shows that the American game may be even older than 100.

The United States Foot Ball Association (USFA) first met at New York City’s Astor House Hotel in 1913, but the initial meeting of the American Football Association (AFA) was in the summer of 1884, in New Jersey. And while the first official international saw the United States defeat Sweden in Stockholm in 1916, the first “unofficial” internationals saw the U.S. lose away and then home to Canada in 1885.

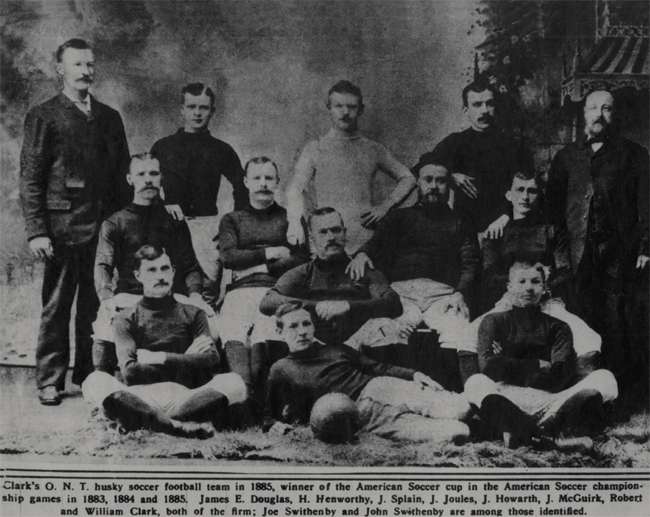

The thread connecting U.S. Soccer to the AFA was literally a thread. Scotland’s Clark Thread Company set up its American operations in Newark, New Jersey after the American Civil War. Clark Thread formed its company team in 1883 and named it after its profitable cotton spool product, “Our New Thread.”

ONT Football Club became the sport’s first American dynasty, and after the 1883-84 season, several of its officials met with representatives from other New York and New Jersey clubs to form American soccer’s first governing body. There they adopted the rules of England’s Football Association, but agreed that the rules were “subject to alteration from time to time.” Tinkering with the rules of “the simplest game” would become a tradition in American soccer.

Six clubs joined the organization in its maiden year, but by 1887 it had over a dozen, including ones from New York, New Jersey, Connecticut and Massachusetts. Prominent businessmen raised $500 to support the fledgling body’s efforts; they used $300 to purchase a trophy for a knockout competition modeled after the English FA Cup. Since there were no soccer-playing figures available, the trophy was topped by a runner with a small soccer ball placed in front of his right foot.

The dean of U.S. soccer historians, Roger Allaway, says both the AFA and its cup competition were regional affairs, but officials hoped the game would expand. (It did, of course, as Fall River, Massachusetts and St. Louis, Missouri are considered other “cradles” of the game).

In the AFA American Cup’s first final, spectators lined a baseball field in Newark for a match between ONT and New York FC. The almost exclusively male, working-class crowd paid a 25-cent admission fee on a bitterly cold Valentine’s Day afternoon. (It was so cold the players only shed their overcoats minutes before kick-off.) ONT had crimson jerseys and matching wool socks along with long white knickers. The New York side wore blue. A blanket of fresh snow hid thin sheets of ice underfoot, and caused many slips and falls throughout the first half.

ONT’s Jack Swithenby, a native of Bolton, England, scored after only 15 minutes. When an ONT forward headed home a second tally before halftime, it sent supporters into a delirium.

“Men could be seen shaking hands and congratulating each other as though they had already won the game,” observed the Newark Evening News. They believed that ONT had one hand on the cup, and the other on the $150 first-place prize money.

New York scored 10 minutes from time to set up a furious finish, but ONT held firm to win what it thought was its first cup. The New Yorkers put the game under immediate protest, accusing their Jersey counterparts of fielding an ineligible player and staging the final on an illegal field, since the goal-posts were too small.

The AFA Executive Committee agreed, and ordered a replay in late April. ONT won again on a lone goal by Swithenby, and some observers said “the playing of the ONT eleven would compare favorably with that of the best clubs of England and Scotland.”

Three years later, on a beautiful April day, ONT made American soccer history by becoming the first team to win three straight championships.

Over time, the cup was lost, but the team’s star, Swithenby, a tavern owner after his playing days, found it in a Newark pawn shop, and rescued it. In the early 1990s, according to Jack Huckel, the former director of the National Soccer Hall of Fame and past president of the National Soccer Coaches Association of America, an antiques dealer from Texas tried to sell it to the Hall for $100,000, many times what the Hall would’ve been willing to pay for it.

Perhaps, that first American soccer trophy still gathers dust somewhere in an unknown Texas antique shop.

The AFA, often accused of being parochial and disorganized, also inaugurated international play. Its top club, ONT, had originally planned to tour England and Scotland, but went north instead, for some friendlies in Ontario, Canada, in 1885. The company paid for all the expenses, and ONT returned with a record of 9-1-1.

When the Western Football Association of Ontario visited the following November fife and drum corps played as the Canadians arrived at Newark’s railroad depot the evening before Thanksgiving. Newark’s mayor, as well as AFA officials, welcomed the visitors at a ceremony at the Newark Roller Skating Rink.

The Canadians easily defeated ONT on Thanksgiving Day, 5-1, but the main attraction, the United States-Canada tilt, drew some three thousand fans to Clark Field, a mostly dirt field directly across the street from a massive new thread mill in Kearny, New Jersey.

Neither team was a real national team, though, with select university players representing Canada, and some of the top players from the AFA suiting up for the United States, including five ONT players. It was more a neighborhood all-star team than a full national team, which is why U.S. Soccer has never recognized the match as an official international.

“The play was very rough at times, so much so that the referee had to interfere several times,” the New York Times reported. “Once two players indulged in a regular fist fight.” The game’s only goal came when a Canadian winger “beautifully centered” for forward Alex Gibson, who duly passed it “through the home eleven’s goal.”

Later that week the skating rink hosted the first recorded indoor soccer game in the world. ONT and their visitors competed for an “international challenge cup,” a series of three games that included both outdoor and “rink” matches.

Those first cup competitions and international friendlies spurred the growth of the game in the metropolitan area, and more teams formed to compete in what was called “the reigning outdoor winter sport.”

In 1894, baseball owners formed the American League of Professional Foot Ball, the first attempt at professional soccer outside Great Britain. It failed miserably, lasting only 17 days. The AFA struggled in the last years of the nineteenth century, even suspending the AFA cup from 1897 to 1906. The body reorganized in early 1906, after a six-week tour of the United States a British team called the Pilgrims in 1905. Jack Swithenby returned the pawned trophy to the AFA to present to the 1906 winners, West Hudson AA of Harrison, N.J.

The historian David Wangerin credited several British soccer teams with reviving interest when they toured the United States in the first decade of the new century. In particular, Wangerin added, two matches in 1911, one in Newark and the other in New York City, altered the course of American soccer history. The AFA didn’t sanction the 1911 tour of English side Corinthians, and suspended teams and players who played against the visitors. Several soccer officials moved to form a new organization, a more inclusive, progressive and national one.

Initially called the American Amateur Football Association, it only sought to govern the amateur game, an area largely ignored by the AFA. Remarkably, the fledgling AAFA sought admission to the FIFA in 1912. Thomas Cahill, who has been called “the father of American soccer,” represented AAFA interests at a FIFA meeting in Stockholm. The AFA was there, too, and FIFA told the rival American organizations to figure out their differences before it could admit the United States to the international body.

The AFA balked, but the AAFA moved to include professional interests at a “national soccer congress” in New York City. In that not-so-famous April 1913 meeting at the Astor House Hotel officials bridged the amateur-professional divide and the United States Foot Ball Association was born. By August, FIFA provisionally accepted the USFA’s petition for membership, and on New Year’s Day, 1914, it was officially a full voting member.

It was a new year, and a new birth of an American soccer organization that defies her age.

daily use of viagra is harmful female viagra approved can you buy viagra online viagra ak47