As friends and family gather to celebrate Thanksgiving, many include an informal kickaround as part of the holiday’s festivities. The tradition of alumni reunion games over the holiday weekend are testimony to the deep roots soccer enjoys in communities all across the United States. Few however, realize they are merely continuing traditions that extends well beyond the founding of soccer itself with the association football code in the 19th century. Pre-code games of foot ball were played informally on holidays well before the Football Association codified the game’s laws in 1863, not only in England, but throughout the British Isles and everywhere its ex-patriates would settle, including the United States.

The first football match in New York City may have been played on Thanksgiving, 8 December 1842 at the grounds of the St. George’s Cricket Club on Bloomingdale Road (now Broadway).

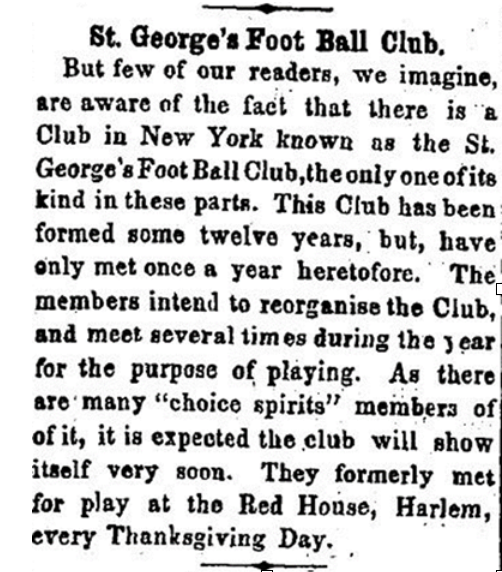

An article in the New York Clipper on 14 October 1854 claims the St. George’s Foot Ball Club as having played for a dozen years, once each year on Thanksgiving:

Harry Wright (most famous as the shortstop on the first professional baseball team) would describe the location of the club’s grounds as “situated at the crossing of Broadway, Sixth Avenue, and Thirtieth Street […] on either side of which were vegetable gardens,” northwest of Madison Square Park and four blocks south of what is now the Empire State Building in midtown Manhattan. Currently the approximate location of Ajax Amsterdam’s newly opened headquarters for operations in the United States, back then the area was farmland on the northern outskirts of the still horizontally (not yet vertically) expanding metropolis in the making.

Harry Wright (most famous as the shortstop on the first professional baseball team) would describe the location of the club’s grounds as “situated at the crossing of Broadway, Sixth Avenue, and Thirtieth Street […] on either side of which were vegetable gardens,” northwest of Madison Square Park and four blocks south of what is now the Empire State Building in midtown Manhattan. Currently the approximate location of Ajax Amsterdam’s newly opened headquarters for operations in the United States, back then the area was farmland on the northern outskirts of the still horizontally (not yet vertically) expanding metropolis in the making.

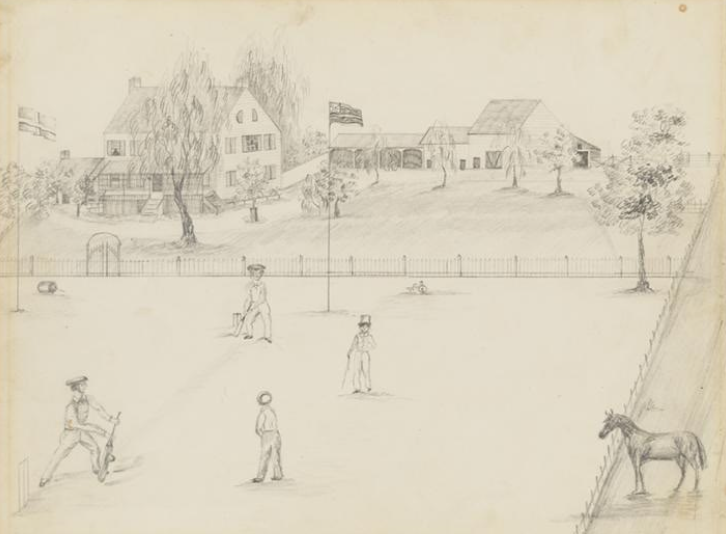

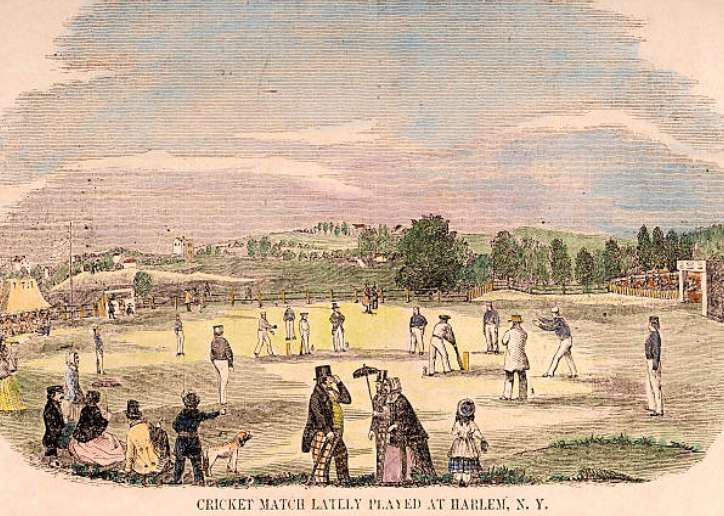

When the construction of 5th Avenue sliced their pitch in two, the St. George’s club moved north to the Red House in Harlem, at 108th St. and 2nd Ave. Wright was born in the year after the St. George’s moved from Bloomingdale Road to the Red House, but his father was an English-born professional cricketer and groundskeeper for the club.

According to Major League Baseball’s Historian, John Thorn, “[a]n ordinance of 8 May 1839 (still in force in 1845) forbade anyone of any age from playing ball anywhere in public spaces,” so any clubs playing any type of ball would need their own dedicated play space. Since the Red House became the home pitch for the St. George’s Cricket Club on 1 May 1846, it is reasonable to conclude the Foot Ball Club of the same name were playing at the Bloomingdale Road pitch.

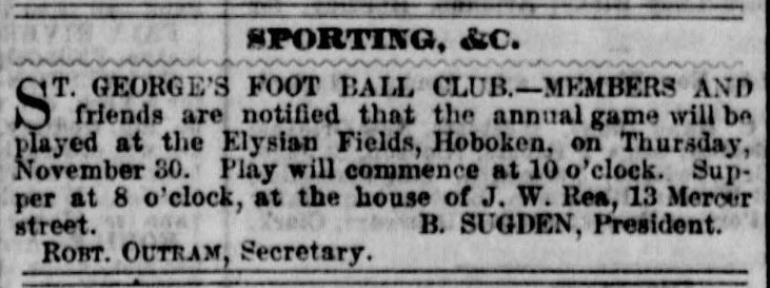

The St. George’s is widely acknowledged as “New York’s first modern cricket club,” formed on 20 September 1838 as the New York Cricket Club but rebranded on 23 April 1839 or 1840 (St. George’s Day) to pay homage to the club members’ birthplace of England. Given that the St. George’s Society of New York was incorporated in 1838, the links between the club/s and the Society (still flourishing) seem obvious in terms of timing and intention, serving the English expatriate community exclusively among the other immigrant communities flooding Manhattan’s expansion. As such, neither the cricket nor the foot ball club have had any sense of mission to proselytize or promote their sporting endeavors, which would explain why the Clipper assumed few readers would be aware of the club and would confirm Tony Collins’s assertion that early clubs “made no effort to attract spectators and paid little attention to those who did watch.” The notice after a dozen years of existence of intention to reorganize suggests a will to “show itself,” reinforced by another newspaper mention, six weeks later in another local newspaper:

This Thanksgiving Day foot ball game announcement further confirms the linkage between the St. George’s Cricket Club and the Foot Ball Club of the same name, as the cricket team (along with the Wright family) moved from the Red House to the Elysian Fields around this time, beginning the tradition of New York sports teams and their supporters commuting to New Jersey to play.

This game notice gives the first hint of a New Yorker pre-code footballer’s identity. An obituary in the 20 January 1900 New York Times for a Robert Outram, who was born in London, lived in Brooklyn, died at age 72 (so born 1828), may well be the secretary mentioned in the notice. Outram would have been 26 years old in 1854. That this Robert Outram was “a lace buyer for Lord & Taylor for a number of years” is a possible connection, for Picton lists George W. Taylor of Lord & Taylor as one of the best-known members of the St. George’s Cricket Club. That Outram was Secretary of the Freemasonic Doric Lodge No. 280 for twenty years also suggests a secretary’s duties were familiar from his time with the foot ball club. With the Doric Lodge he was likely involved with the building of New York’s Masonic Hall in 1873. He also served as Lodge Master for 1882. So there may be an invisible transatlantic fraternal thread with those who would meet to form the Football Association in London’s Freemason’s Arms in October 1863. Unless further searchable digitization exposes more about these footballers, we are left with no more than this conjecture as to the lives of those earliest players of pre-code football in New York.

Disputes over whether the form of “foot ball” Outram and his club mates would have played cannot be tipped in the favor of lovers and historians of the kicking and dribbling “beautiful” game or those who prefer the Rugby or gridiron carrying codes. As Collins claims,

“Clear differentiation between the association and rugby codes did not emerge until the 1870s […] In fact, all forms of football that were played in the 1850s and 1860s had far more in common than that which set them apart. Kicking and handling the ball differed only be degree. Rather than being two distinct codes, there was one football with a spectrum of views about how it could be played.”

The footballers of the St. George’s club may then be the first to enjoy a Thanksgiving Day kickabout.

Thus New Yorkers can claim a football club from their city that was older than England’s Sheffield FC (formed in 1857), certainly older than the Oneida’s of Boston who claimed to be the country’s oldest (formed in 1862, though they seem to have played a carrying, not a kicking game), though St. George’s Foot Ball Club of New York would not be as old as The Foot-Ball Club of Edinburgh, which (formed in 1824) can claim to be the world’s first.

Sources:

Wright, George. “Early Days of Cricket in America,” Spalding’s Cricket Guide, 1907, 14.

Thomas Picton, “Pioneer Cricketers in America,” New York Clipper, 5 October 1878, 4.

P. David Sentence, Cricket in America, 1710-2000 (Jefferson, NC: McFarland, 2006), 14.

Tom Melville, The Tented Field: A History of Cricket in America (Bowling Green, OH: Bowling Green State U Popular P, 1998), 11.

“Constitution,” St. George’s Society of New York, https://www.stgeorgessociety.org/our-history/

Tony Collins, How Football Began (New York: Routledge, 2019), 21.

R. ‘.W.’. Gary L. Heinmiller, ed., “Grand Lodge of New York – Masonic Lodge Histories: Lodge Nos. 263-294,” 1912 Grand Lodge Proceedings, http://www.omdhs.syracusemasons.com/sites/default/files/history/Lodge_Histories_-_1912_Proceedings.pdf

John Hutchinson and Andy Mitchell, The World’s First Foot-Ball Club (Andy Mitchell Media, 2018).

David it’s more after Christmas or New year in Europe the a and b team play against each other and then eat and the german drink have exstend family party’s but here they don’t have tomany clubs house where in Germany it’s every club has there own club house.Prorel rules the land there .

Thanks for this great article Dave. So little info on early soccer in the U.S. This is great.