Author’s Note: I would like to extend my sincere thanks to Ed Farnsworth and Tom McCabe for their invaluable assistance and guidance during this project. Their generosity of time and spirit of collaboration is greatly appreciated.

“Bareheaded and with bleeding knees exposed to the winter’s chill” was the New York Herald’s description of the 1918 New York Footballers’ Protective Association (NYFPA) international series clash between Ireland and the team representing Continental Europe[1]. Entertaining New York area soccer fans since 1912, the NYFPA contests featured the top local players representing unofficial national teams of their country of origin. Ireland, the 1917 winner of the international series, defeated the stubborn Continental team at Manhattan’s Lenox Oval by 7 goals to 2. Samuel Bustard, center halfback and captain of the Ireland team, played a stellar game in the February freeze and scored two of the Ireland goals. No one at the time knew it would be Bustard’s last game before he would be reported dead from the Spanish Flu on October 14, 1918.

This article introduces Samuel Bustard, an Irish immigrant from Belfast, and details his journey through American soccer in the first quarter of the twentieth century. Although not a household name, Bustard played for several elite teams and experienced firsthand many of the major trends and events that transformed soccer in the New York Metro area during the 1910’s and 1920’s. These trends and events are addressed in detail and viewed through the filter of Bustard’s life and career. Bustard’s unique story also includes an encounter with the deadly second wave of the Spanish flu pandemic in October 1918. That encounter left Bustard’s family searching for answers and resulted in Bustard being “one of the few men who have been able to read his own obituary notice.”[2]

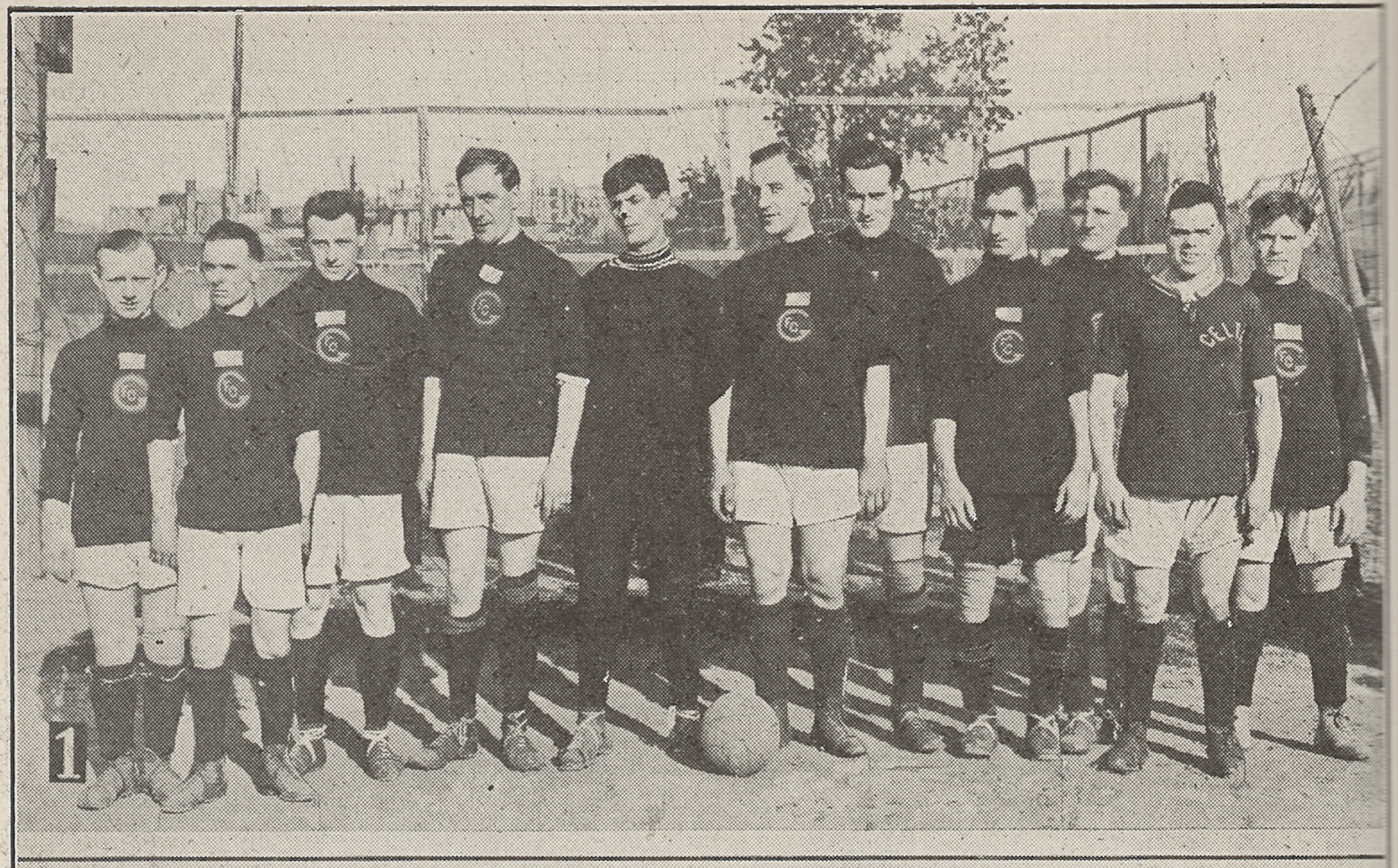

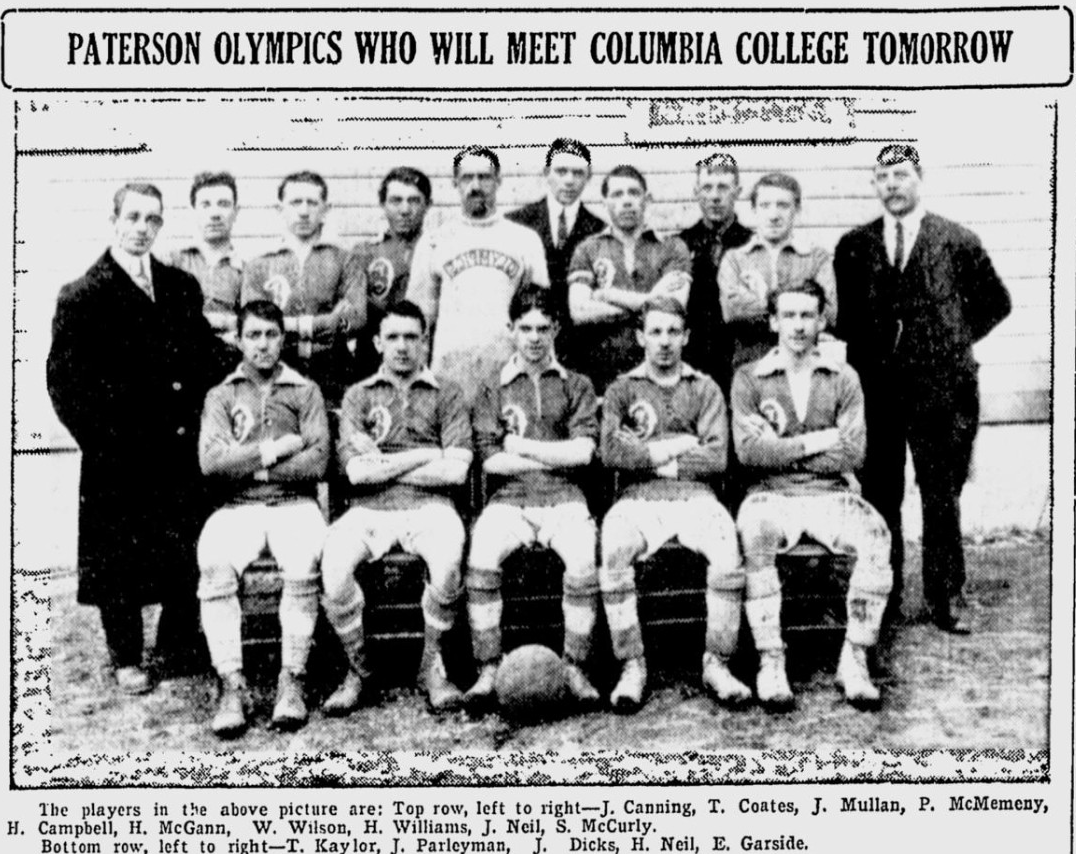

Bustard’s story starts in October 1912, when the Paterson True Blues were starting what would be a memorable season, culminating in the capture of the coveted American Football Association (AFA) Cup and a narrow second-place finish to West Hudson AA in the National Association Football League (NAFL). The True Blues’ first opponent in the AFA Cup competition was a plucky amateur eleven from Paterson named the Olympics. The Olympics were known as a strong amateur side, but the presence in Paterson of the professional True Blues, Rangers, and Wilberforce clubs ensured the Olympics received little press. Looking to strengthen their side before the upcoming match, the Olympics signed several new players including a diminutive 20-year-old Irishman living in Passaic, NJ, named Samuel Bustard, who was referred to by the Paterson papers as having played “on a fast team in Belfast.”[3] Nonetheless, the teams entered the weekend with the Blues as heavy 5 to 1 favorites to capture the cup tie.

“Taken by surprise and nearly played off their feet,” the True Blues managed to squeeze past the Olympics 2-1 on a late penalty kick by former Clark AA star Charlie Fisher.[4] The Olympics, however, protested against the similarity of uniforms worn by the True Blues, and won a replay that was held the following weekend at Paterson’s Willard Park.[5] Angry over the protest and now aware of the Olympics’ undeniable quality, the True Blues decisively won the replay 4-0. Samuel Bustard made ignominious history by scoring a somewhat comical own goal in the second half that secured the Blues’ victory.[6]

Despite this mishap, Bustard must have impressed. He reached the professional ranks the following week when he was signed by the Paterson Rangers for the 1912/13 NAFL season.[7] In his debut against Brooklyn FC, the Paterson Press referred to Bustard as having played “championship soccer” at right halfback in a 3-0 victory for the Rangers.[8] Meeting up again with the True Blues in January 1913, the Morning Call was quick to give praise:

In distributing bouquets for good work well done nobody wants to overlook the fact that Bustard, center half for the Rangers, put up the game of his life. For a small man the sandy haired little back is a wonder, and the Blues found him a difficult customer to handle.[9]

Bustard continued to play for the Rangers through the end of the 1914/15 season, the last season the Rangers would ever play as a professional organization. For the 1914/15 season, the Rangers gambled on the creation of an “All-Star Aggregation” and manager William Ritchie was given a blank check to pursue the best local talent. The high-priced talent included several former Clark AA, West Hudson AA and Paterson True Blue stars such as Adam Esplin, Alec Monteith, Jack Neilson, and Charlie Fisher.

All-Stars and strikes

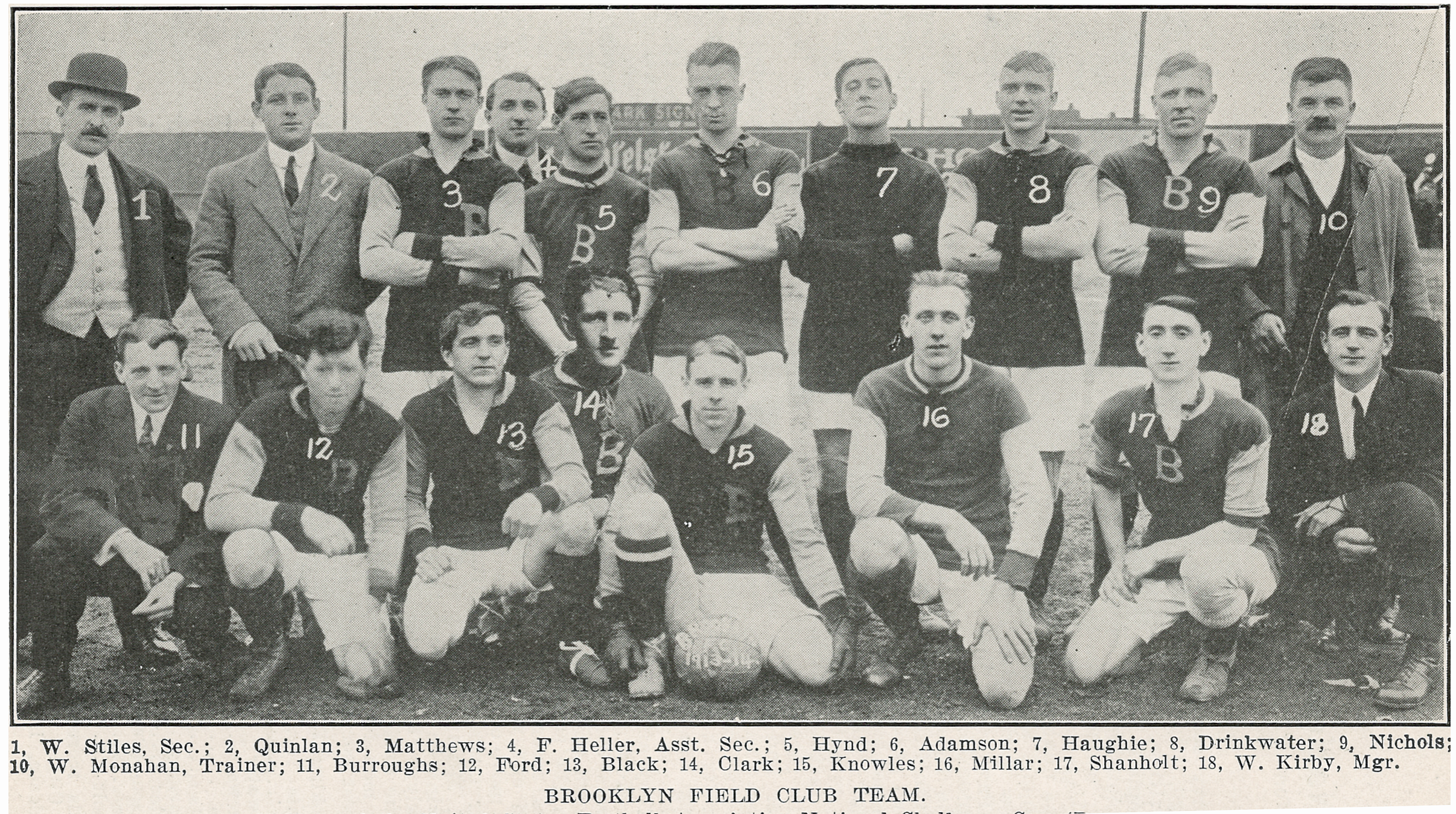

The notion of an All-Star Aggregation was not new to soccer at this time, with the NAFL title and inaugural National Challenge Cup being claimed the year before by the Brooklyn FC “All-Stars.” Brooklyn was referred to as the “$10,000 team” (the same buying power as $261,000.00 in 2020) by the Newark Star and included future international stars Neil Clarke, James “Bow” Ford and Bob Millar.[10] All of these players were off to greener pastures the following season.

Paterson had intimate experience with the All-Star concept during that era with Wilberforce FC and True Blues each fielding similar elevens. Wilberforce left the local Sons of Saint George League as champions and subsequently finished the 1909/10 NAFL season in the tail-end position. Realizing the need for a complete overhaul to remain relevant in soccer-rich Paterson, team executives proceeded to secure the services of several members of the Clark AA team that had recently disbanded as a professional entity after the 1908/09 season. The new team encountered moderate success – two consecutive NAFL second-place finishes and a third-place finish – before collapsing after being caught fielding an illegal player during a 1913 AFA Cup tie.

The True Blues went the “All-Star” route for the 1912/13 season, the same season they encountered the Paterson Olympics in Bustard’s debut. This True Blue team featured ex-West Hudson and Wilberforce stars added to the best of the current True Blue squad. The Blues would eventually take home AFA Cup honors after three epic battles with the Tacony eleven of Philadelphia. Jack Neilson, who bounced from Clark A.A. to Wilberforce F.C. then to the True Blues, would score the eventual cup winning goal. The Blues finished in second place in the NAFL race, and if not for a late-season slip up against the lowly Brooklyn FC, may likely have taken the championship and the “double.”

The Paterson Rangers’ All-Star experience was not as successful. A seventh-place finish in the NAFL and early exits in the AFA and National Challenge Cup competitions affected fan turnout and proved too much to overcome. The Morning Call reported, “The Paterson Rangers had an ‘all-star’ team last season, which cost its backers a big roll of money to float and owing to the failure of the Rangers to go far in the big soccer tournaments the manager, it is said, lost a lot of money.”[11]

Even the famous True Blues were not immune to the waning fan support in Paterson. Despite raising a “signing-on fund” in July 1914 in order to salvage their “lost prestige,” the True Blues fielded a team well below their usual standards.[12] After playing several games with makeshift lineups and partial teams, the Blues threw in the towel on January 15, 1915, formally resigning from the NAFL.[13] Exacerbating the situation, the Rangers and Blues were two of four teams suspended by the NAFL “pending the settlement of their financial relations with the league.”[14] Faced with a diminished fan base and already in debt to the league, the two clubs folded before the start of the 1915/1916 NAFL season. The Haledon Thistles attempted to represent Paterson in 1915/16, but poor fan support led to their resignation from the NAFL in December 1915.[15] Obviously Paterson was experiencing hard times.

Paterson soccer fans, known to be fickle even in the most successful of times, may have been financially unable to support their local teams. There is significant evidence of financial strain resulting from the unsuccessful Paterson Silk Strike that lasted for nearly five months, ending in late July 1913. The strike eventually ended when all “the resources of the strikers – their savings, their credit with store owners, and the help they received from local supporters – were exhausted.”[16] The 1915 New Jersey State Census revealed a net population loss in Paterson of 785 from the 1910 Federal Census, with the losses “ascribed to the great silk strike of three years ago which caused many workers to leave the city, and to the removal of others due to the business depression closing some of the other manufactories there.”[17] Undoubtedly, many supporters of the local Paterson soccer clubs were included in the group suffering from the strike’s aftermath. The war of attrition was won by the local Paterson silk manufacturers, but the loss of Paterson’s professional soccer teams may have been unfortunate collateral damage.

Building a reputation

Looking for a new team, Bustard was given a trial at halfback for the famous West Hudson AA in a 1-1 tie against the Brooklyn Celtics on September 19, 1915.[18] Again, Bustard must have impressed as he was signed by the Hudsons for the 1915/16 season.

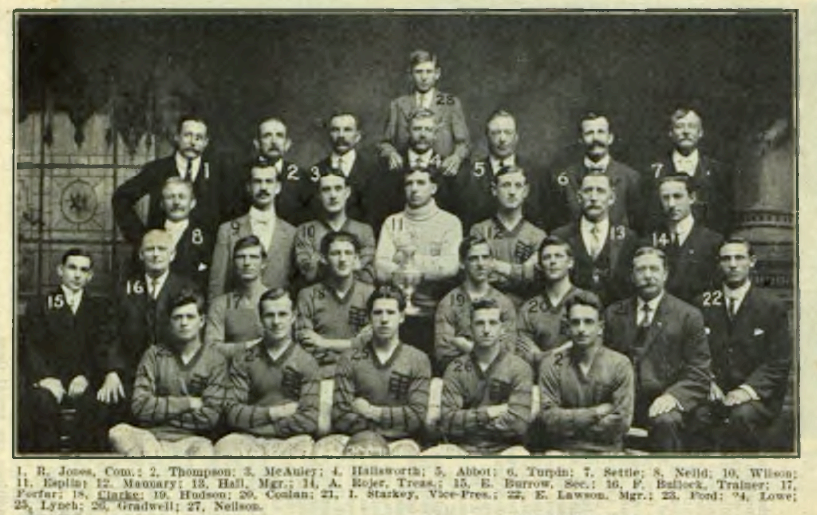

West Hudson AA was one of the most recognizable teams in the early years of American soccer. Five-time champions of the NAFL and three-time winners of the AFA Cup, the Hudsons were also familiar to fans as far away as Fall River and St. Louis through the many friendly matches played with clubs in those cities. The 1905/06 West Hudsons were known locally as the “triple champions” for their victories in the AFA Cup, Metropolitan League and New Jersey State League. The 1911/12 squad recorded a local “double” by winning the NAFL title and the AFA Cup.

Breaking into an established West Hudson side would have normally been a formidable task, but the 1915/16 West Hudsons were not as strong as in seasons past. Player mobility was on the rise, especially between the NAFL clubs and teams from New York. The Hudsons would lose several stars of recent years including Len Brierly, Ken Napier, George Knowles, Buck Cooper and Jimmy Ingram, who jumped ship to the Continental Football Club of New York.[19] Nevertheless, the West Hudsons were strengthened by the addition of several players made available by the collapse of the Paterson clubs, including George Murray and Alec Lowe from the True Blues. With the Hudsons, Bustard was played at numerous positions on the forward line before settling at his preferred center halfback slot.

The 1915/16 season was not a success by West Hudson standards with a fourth-place finish in the NAFL, a stunning first-round exit in the AFA Cup, and a one-goal defeat in the National Challenge Cup quarterfinals before 5000 spectators to eventual champion Bethlehem FC.[20] The AFA Cup loss to the Jersey AC was only the second first-round exit in the history of the fabled club, with their other defeat coming against the Fall River Rovers in 1908. Nonetheless, Bustard, still only 23 years old at the end of the 1915/16 season, continued to improve. Praises from the Newark Eagle included “it was Sammy Bustard, the smallest player on the field, who did the best work for the Hudsons,” and “Sam Bustard, regarded as the cleverest man on the Hudson team, played his usual crafty game.”[21]

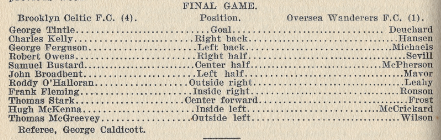

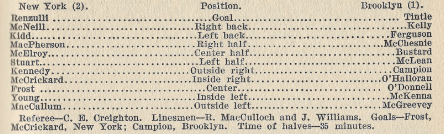

Bustard’s trial for the West Hudsons on September 19, 1915, also put him on the radar of the New York Amateur Association Football League champion Brooklyn Celtics, who were not shy in their pursuit of the Irishman. The April 1916 American Cricketer listed Bustard, along with Tommy Stark, Archie Stark, and George Tintle, as “players of the New Jersey National League, who have signified their intention to play with New York Clubs, that is, when their own clubs are idle.”[22] Bustard would formally join the green and white for the 1916/17 season and go on to become a “shining light” for the popular New York club.[23] With Bustard in the lineup, Celtic finished with a record of 24W-3L-2D and won the New York Amateur Association Football League title for the fifth straight year, the Southern New York State and La Sultana Cups, and were semi-finalists in the AFA Cup competition.[24]

Unfortunately for Bustard, Celtic met Bethlehem Steel FC in the second round of the 1916/17 National Challenge Cup. As was the case the previous year with the West Hudsons, Bethlehem proved to be the better side. Bustard, however, was one of the Celtic players who “gave an excellent account of themselves,” according to the Philadelphia Inquirer.[25]

Like many players of his day, it was not uncommon to see Bustard in a different uniform when his schedule allowed. Sammy was comfortable as a Ranger or a Celtic, and occasionally suited up for the West Side Rangers, a predominantly Irish team in the New York Metropolitan League that played out of Chelsea Park. Coincidentally, the core of the West Side Rangers consisted of players who shared the field with Bustard on the Paterson Rangers. Bustard also received “special permission” from Brooklyn Celtic to play for his hometown Passaic FC in the Field Club Soccer League of New York and New Jersey.[26]

Bustard was frequently selected for area all-star elevens while with West Hudson AA and Brooklyn Celtic. He also frequently represented Ireland in the annual international competitions under the auspices of the NYFPA. The NYFPA was formed in August 1912 “for the purpose of devising ways and means of protecting players against accidents on the field.”[27] The association raised funds through individual 50 cent annual player membership dues and “Charity Cup” matches between unofficial national teams representing local players of Continental Europe, American, English, Irish, and Scottish descent.

Ireland won the 1917 championship over the American team with Bustard and several other Brooklyn Celtic players forming the nucleus of the side. The defeated American squad contained no less than four members of the first recognized United States Men’s National Soccer Team (USMNT) that traveled to Norway and Sweden the previous year, finishing with a 3W-1L-2D record. During that period Bustard was the focus of a Passaic Herald News article describing his exploits on the soccer field with the Irish. The article stated that “Bustard is a great favorite among his fellow employees” and “it took the experts about two minutes to select the local man to play for the sons of Auld Erin.”[28]

Bustard also represented Brooklyn in the New York vs. Brooklyn annual inter-borough game under the auspices of the New York State League. He was also selected to represent New Jersey in an inter-section contest between the select teams of New York and Pennsylvania against New Jersey on New Year’s Day 1918. He lined up in that game next to Clarence Smith, another member of the 1916 USMNT.[29]

In an era of moderately sized athletes, Bustard was often described as being the smallest player on the field at only 5 feet 2 and one half inches tall. The Passaic Daily News commented, “Bustard is about the smallest man playing the game in the country, but makes up in speed what he is shy in length of limb.”[30] His favored position was center halfback, a position that often placed him against taller and heavier opponents. Bustard was never shy to mix it up, however, as referenced by his “quick exchange” with Bethlehem Steel inside right Fred “Chiddy” Pepper in a NAFL game in November 1917.[31] A fine athlete, Bustard also played point guard for the Passaic YMCA “Seniors” basketball team.[32]

Paterson FC of the NAFL, financed by Amie Van De Weghe and managed by Paterson stalwart Tommy Garside, was next to obtain Bustard’s services.[33] Paterson FC was the first elite team to represent the Silk City since the days of the True Blues, Rangers, and Wilberforce FC, and included many former Paterson stars such as scoring machine Jimmy Hayes, George Murray, “Tot” Morel, Tommy Gradwell, and consummate journeyman Jack Neilson.[34] With Bustard on board, Paterson shocked the local soccer world by winning the 1917/1918 NAFL championship over perennial powerhouse Bethlehem Steel with a record of 12W-1L-1D. Bethlehem suffered a late-season 4-2 loss to the West Hudsons that sealed the title for Paterson, with the defeat being “the first time in the history of the famous eleven that they had four goals scored on them.”[35] Bustard, however, would not complete the storybook season for the champion Paterson kickers.

Soccer supports the war effort

In contrast to prior seasons when the weather and/or cup tie conflicts were the primary reasons for schedule disruption, 1918 was a particularly difficult year for soccer in the New Jersey/New York metropolitan area due to problems on a global scale. America’s involvement in World War 1 had progressed to the point that by the summer of 1918 about a million US soldiers had already arrived in France. By the Armistice of November 11, 1918, approximately 10,000 fresh soldiers were arriving in France daily.[36]

The enlistment of soccer players in the armed forces of the UK, however, started affecting teams throughout the New York and New Jersey area years earlier. The New York Tribune commented, “nearly half of the association footballers in the United States are Canadian, Irish, Scotch or English born, or descended from such stock.” As such, “soccer football felt the effects of the war long before the entrance of this country into the cataclysm.”[37] In what was not an isolated incident, six members of Newark FC enlisted in the British Army in August 1915.[38] One of the six, William Montgomery, was killed in a trench in France in October 1916 as a member of the Argyle and Sutherland Highlanders. George Richardson, the Newark center forward who accompanied the West Hudsons during their December 1912 exhibition in St. Louis, was another of the six. James Dunlop, a midfielder on the Newark club, was injured in France in 1916 and by the summer of 1917 had been commissioned as a captain.[39] Other local players joined the ranks of far-off units such as the Seaforth Highlanders, Gordon Highlanders, and the Canadian Expeditionary Forces.

The United States’ entry into the war in April 1917 signaled that American players would soon join the ranks of the enlisted and conscripted. George Tintle and James Ford, New Jersey players and members of the 1916 USMNT, were called in the first draft; they later joined fellow international Buck Cooper on the Camp Dix team in New Jersey. The USFA soon felt the war’s impact when only 54 teams joined the 1917/18 National Challenge Cup competition as opposed to 88 clubs the year before.[40] As 1918 arrived, the player drain significantly affected the ability of teams and leagues to operate. Thomas Cahill stated that “from among the 42,500 players of approximately 3,500 organized soccer clubs in the United States before this country’s entrance into the war more than 18,000 exponents of the kicking game are in government service.” Furthermore, “this would mean that considerably more than 1,000 soccer clubs have either been forced to disband for the duration of the war or to fill the places of patriotic regular players with players of less experience.”[41]

The “maelstrom of changing events” reached its zenith in the latter half of 1918.[42] Joe Booth, organizer of several early soccer leagues in Connecticut and a member of the National Soccer Hall Of Fame, reported in the Bridgeport Telegram that of the four semi-finalists in the 1917/18 National Challenge Cup competition (Bethlehem, Joliets of Chicago, West Hudsons and Fall River Rovers), only one was still in existence. “All these teams made good money out of the competition but owing to the war, only the Bethlehem team is in existence this season.”[43] The NAFL was forced to operate with only six teams for the 1918/19 season as Disston AA of Tacony and the Jersey AC joined the West Hudsons in losing nearly all of their players through enlistment and the draft.[44] Even though Bethlehem would survive (and prosper), the team was not immune to the long arm of the United States military. Tommy Murray, James Murphy, and recently re-signed USMNT midfielder Neil Clarke were drafted from their ranks in 1918. The New York Tribune reported that while “Murray, Murphy and Clarke were employed by a firm doing highly essential war work, they were not indispensable to the industry in their occupations with the Bethlehem Steel Company.”[45]

Samuel Bustard was among those drafted; interrupting his successful season with Paterson FC. The Passaic Daily News announced that on April 26, 1918 Bustard was accompanying the other drafted men from the city to Camp Dix, New Jersey. In an article titled “Sammy Bustard to ‘Kick Off’ To the Kaiser,” the News described Bustard as “one of the best forwards playing soccer football in the country today.”[46]

The shipyard menace

Waiting in the wings to capitalize on the misfortunes of the smaller local clubs were the newly formed teams of the shipyard and munitions plants, also known as the “War Work Teams.” C. A. Lovett of the New York Tribune wrote that “with the lure of ‘soft’ jobs at ‘wages’ that amount to high salaries, it has become an easy matter for the soccer managers of dozens of shipyards in the East – and more particularly of the Middle Atlantic states – to sign to contracts virtually the choice of the dribblers remaining out of the military service.”[47] The Bethlehem Globe commented,

The draft together with voluntary enlistments have played havoc with a good many of the teams in the country and at the same time open up an avenue by which newly organized teams could secure the cream of the players. In many instances where only a half dozen more players remained for the team, the best of these players were lured to the shipyards and since the managers could be a bit choicy in their selections unusually strong teams have been organized. This means that the competition will be as strong if not stronger than last year and that the winners of the cups will not have easy sailing. [48]

Conflicts over the illegal recruitment of players reached a boiling point in December 1918. New York FC’s Hugh Magee, the former Irish middleweight boxing champion, levied charges against members of the Robins Dry Dock and Federal Shipbuilding teams. A special investigating board of the USFA was called to probe reports of “tampering” with professional players already under contract, a violation of association rules. Jimmy Hayes, the Paterson scoring machine now with the Robins, was named as the “agent” who brought about the “disaffection” of Ernie Garside with New York FC. The board provided recommendations that were unfortunately not made public, but Lovett was able to shine some light on the excesses that were rampant at the time:

While some shipyard club representatives were inclined to scoff at the published reports that wages as high as $21 per day were paid to shipyards employees who did little else but play soccer, York [Secretary of the Federal Shipbuilding AA FC] told of a Federal Ship team star who was rated as an expert in one phase of the shipbuilding industry and whose weekly pay checks ran as high as $294.[49]

Meanwhile, enlistment and the draft had taken so many top players Lovett wrote “a number of the cantonment and training station teams will be among the first ranking clubs in the season.” He also mentioned, “Army and Navy clubs will play numerous games, however, with the stronger shipyards and munitions works elevens and with the principal clubs of all large cities near which camps or stations are located.”

Camp soccer and the Spanish Flu

The Army and Navy both placed a strong emphasis on recreational sports in their training to develop the camaraderie, strength, and fighting spirit required for battle. Camp Upton, located in Yaphank, Long Island, developed a soccer program that was run by Duncan Morrison, longtime manager of the Clan MacDonalds and future part-owner of the Brooklyn Wanderers American Soccer League franchise. The “Yaps” featured players that previously competed with the New York FC, Clan MacDonalds, Clan MacDuff, and Yonkers FC.[50] The soccer team representing the Great Lakes Naval Training Station in Illinois included a dazzling array of St. Louis stars, including “Hap” Marre, and the duo of George Corrigan and Andy Hack, who apparently turned down an offer from Thomas Cahill to be members of the first USMNT that toured Sweden and Norway in 1916.[51] Up in Massachusetts, the soccer team at Camp Devens was composed mainly of players from the “cradles” of Fall River and New Bedford, including several members of the famous Fall River Rovers and Pan Americans.[52]

Down in New Jersey, Camp Dix was aggressive in promoting recreational sports and the competition of its service teams against non-service clubs in baseball, soccer, and football. Dix also hosted the first game at an Army cantonment between outside teams in January 1918 when Standard Roller Bearing of Philadelphia played the Henry Disston Industrial League team at the camp. The Philadelphia Inquirer wrote that “soccer has made splendid headway at the camp” and soldiers had great interest in the game. The Camp Dix eleven appeared to be quite active, even playing the Newark Scottish-Americans on May 12, 1918, at Clark’s Field, after the NAFL contest between Bethlehem and the West Hudsons. George Post, a former fullback on the Newark Scottish-Americans, captained the Camp Dix eleven.[53]

The interaction of service teams and non-service teams was great for moral and personal development, but the interaction may have contributed to the terror that was about to follow. Lurking in the shadows was another, more deadly foe, the 1918 Spanish Flu pandemic.

The origin of the Spanish Flu is unknown, but the first case in the United States was reported in March 1918 at Camp Funston, Kansas. Taking advantage of the close quarters kept by service personnel at the military camps and the high level of troop mobility between the various encampments, the flu spread quickly from there. The death and disruption caused by the H1N1 virus began to hinder the readiness of the American forces and seriously threatened troop mobilization. However, the German Army’s great spring offensive of 1918 created a dire need for American troops at the Western Front, and the United States chose “to prioritize mobilization, accepting the human toll as a grim necessity.”[54] The influenza was carried to Europe with the US troops, and by the time the pandemic was over more people would die from “La Grippe” than the combined military and civilian deaths resulting from the Great War.

The pandemic spread in three distinct waves, the first starting in Kansas in March of 1918, the second wave coming in the fall, and the third occurring in the winter of 1918 and lasting into the spring of 1919. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), “an estimated 1/3 of the world’s population was infected with the 1918 flu – resulting in at least 50 million deaths worldwide.”[55] Roughly 675,000 Americans would succumb to the disease, with many deaths occurring during the second wave that hit in September of 1918.

Although many influenza cases were reported in American military encampments in March and April, the first wave turned out to be relatively mild. Tommy Swords, the great American-born forward of the Fall River Rovers who captained the 1916 USMNT, reportedly contracted the flu in April, a few weeks before the Rovers were to meet Bethlehem Steel in the finals of the 1917/18 National Challenge Cup. Although Swords was “not able to practice regularly”[56] leading up to the game, he did participate in the final played on May 5. In contrast to the previous year when Swords scored the only goal in a 1-0 victory over the Steelmen, Swords “seldom looked dangerous”[57] in the May 5 contest (a 2-2 deadlock) and failed to score in Bethlehem’s 3-0 victory in the May 19 replay.

Influenza migrated to Europe with the infected troops, but with mostly non-lethal results. In mid-August, England reported the first wave had all but stopped. Reports, however, of the flu’s rampage through Europe were by then circulating in American newspapers. The Wichita Beacon carried an English article on July 6 that said “An Epidemic of Influenza Threatens the Whole World” and questioned if the disease would spread to the United States and “cripple that country’s war industries also.”[58] New York Health Commissioner Royal Copeland tried to assuage the fears of New Yorkers by downplaying reports of influenza’s spread, and oddly went as far as warning people not to kiss, “except through a handkerchief.”[59] Copeland’s message received a lot of press, and a week later the Ithaca Journal printed a poem titled “Kiss Through Your Handkerchief” from a man struggling to comply with the Commissioner’s social distancing guidelines and recommendations for personal protective equipment (PPE):

Oh, where is my han’ky, mother?

I want to make a call

On my best girl, and, dear mother,

I need that most of all.

For I cannot leave her, mother,

Without a good night kiss,

And without a han’ky, mother,

That kiss I’d have to miss.

Tho I am strong, I am mourning,

‘Cause she won’t take a chance,

But she’s read the paper’s warning,

Of influenza’s advance.

So give me my han’ky, mother,

I want to make that call.

I’d rather kiss that way, mother,

Than not kiss her at all.[60]

The second wave

Copeland was wrong. Experts believe a more virulent strain of the flu may have emerged in the trenches of Europe and returned home in late August with supply ships and ships carrying sick and injured servicemen. Influenza took hold on Boston’s Commonwealth Pier by August 27 and then quickly spread to Camp Devens. “By the end of September, medical officers at Camp Devens had counted more than 14,000 cases of influenza – about 28 percent of the camp population – and 757 deaths.” “Wartime transportation routes with its human hosts” would ensure the spread of the disease to other encampments and cities.[61]

Camp Dix held a “field day program in honor of General Pershing’s birthday” on September 19 that was witnessed by over 20,000 soldiers and civilians.[62] The program was held on the parade grounds, now known as Doughboy Field and the current site of frequent regional soccer tournaments. The program featured numerous riders from the West who had made their way to Camp Dix as part of the 34th Division, including “Billy” Simons, holder of the world’s rough riding championship for three consecutive years. The festivities also included a formal dedication of the base hospital, which included quiet reading rooms and rooms reserved for “officers of the medical detachment.” Within days the hospital would be filled to capacity with suffers of the great influenza.

Camp Dix encountered its first flu activity on September 18, with several hundred cases and one death reported. In an effort to combat the epidemic better than Camp Upton and Camp Devens, all 50,000 of the cantonment’s soldiers were advised to gargle “at least twice or preferably three or four times a day” with a solution of salt water or two percent tincture of iodine.[63] It is unknown if the gargling measures prevented any illnesses, but Camp Dix began a quarantine on September 26 after the deaths of 54 soldiers from the flu in the first week.

Such trends continued for many of the military encampments across the country. Due to the frequent interaction of civilians with camp personnel, influenza quickly spread to neighboring communities. One of the most well known cases was from Philadelphia, where the flu spread to the Navy Yard in late September on a ship from Boston. At least 525 people at the yard had contracted the illness and 70 had died by September 28 when city officials decided to ignore appeals from local physicians and go-ahead with a Liberty Loan parade. In 72 hours every hospital bed in the city was filled. By the third week in October, the influenza “had afflicted tens of thousands of people and claimed the lives of more than 4,500 Philadelphians.”[64]

The spread caused the New Jersey State Board of Health to impose quarantine on October 7 which banned all public gatherings and closed churches, saloons, theatres, lodge rooms, and other places where numbers of people congregated. This ban also included soccer, and along with Eastern Pennsylvania, the game was suspended, albeit with varying levels of success.[65] The Paterson Morning Call reported on October 11 that “for the first time in the history of soccer football in this country scheduled games have been postponed because of an epidemic.” The Bridgeport Telegram reported “other centers where the game is being suspended owing to the ‘flu’ [are] Ohio, Illinois, Missouri and almost the whole of New England.”[66]

Unlike most influenza, which exhibits a “U-shaped” mortality curve by age reflecting higher mortality rates for the very young and the very old, the Spanish flu presented a “W-shaped” curve – reflecting an additional peak in mortality among those between the ages of 20 – 40. One possible cause for this additional peak in mortality was death due to a severe overreaction of the immune system, also known as a “cytokine storm.” John Barry describes:

Young adults have the strongest immune system in the population, most capable of mounting a massive immune response. Normally that makes them the healthiest element of the population. Under certain conditions, however, that very strength becomes a weakness.[67]

The “healthiest element of the population” – adults in the prime of their lives – included members of the association football community across the United States and the world. C. A. Lovett reported on October 13 that “six members of the Babcock & Wilcox eleven, of Bayonne, are ill with influenza, necessitating cancellation” of their game with the New York FC. Lovett also provided a list of the local soccer administrators affected by influenza:

One of the first officers of the United States Football Association – William D. Love, of Pawtucket, R.I. – died a few days ago of influenza-pneumonia. Ex-President John A. Fernley, of Central Falls, R.I., was very low from the disease recently, but is on the road to recovery. James Marshall, of Kearny, N.J., New Jersey State Football Association delegate to the national council last spring, has lost his wife and her sister. The entire family of Andrew N. Beveridge, secretary of the New Jersey State Football Association, is ill with the grip, as also is a daughter of National Secretary Cahill, at his Newark home.[68]

Also dead from influenza was Robert Spencer, a member of the Paterson True Blues during their glory days in the 1890’s. Born in England, he played in the Lancashire League for Burnley Union Star and Brierfield before coming to the United States and having a memorable career, playing for Paterson Thistle, Paterson True Blues, Newark Caledonians, and Fall River Olympics. Spencer won the coveted AFA Cup competition three times, with the Olympics (1894), Caledonians (1895), and True Blues (1896). He also had a brief tour of the professional leagues of 1894, being originally signed by Brooklyn in the American League of Professional Football (ALPF). He was released by Brooklyn and signed by Boston, only to run afoul of the Boston management for his visits to Paterson. Spencer completed his tour by breaking his contract with Boston to play for the Paterson team in the American Association of Professional Football Clubs (AAPF).[69]

The news would only get worse.

Bustard “is one of the few men who have been able to read his own obituary notice”

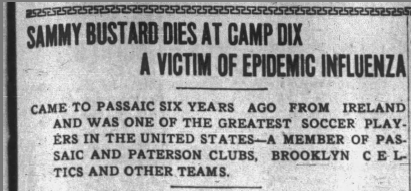

On October 14, newspapers as far away as Washington D.C. reported the death of Samuel Bustard. The New York Tribune wrote, “soccer players were shocked to learn of the death from Spanish influenza of Sam Bustard, of the Paterson Football Club, formerly famous as a center halfback for the Brooklyn Celtics, who before they disbanded because of the war had captured the New York State championship five times.”[70] The Passaic Daily News provided more detail, stating that Bustard had died of influenza at Camp Dix, where he had been since April 26. Bustard, the report explained, left behind a wife and child in Ireland, and apparently made “no claim for exemption on account of his family connections.”[71]

Death from the flu was often quick, just hours or days from the onset of symptoms. Many people who were afflicted, however, recovered within several days. Peter Sweeney, one of the six Babcock & Wilcox players suffering from the flu, was reportedly “lying dangerously ill” on October 13.[72] By October 29, the Morning Call reported that Sweeney had “recovered and played in the drawn game on Sunday” against the Federal Shipbuilding FC. Sweeney went on to have a fine career, winning the National Challenge Cup in 1920/21 with Robins Dry Dock before losing in the final the following year as a member of Todd Shipyard. As exposure to the flu was known to cause long-term physical ailments, Sweeney’s history with the disease may explain why he was later “at death’s door” from double pneumonia in 1923 while playing for the Paterson FC.[73]

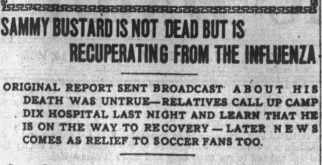

In an atmosphere devoid of good news, fans of the beautiful game were about to get some. On October 15, the Passaic Daily News reported:

Sammy Bustard is one of the few men who have been able to read his own obituary notice. Instead of being dead from influenza at Camp Dix, Sammy is in the base hospital and doing nicely.

Samuel Bustard was not dead and he would indeed recover. Bustard’s aunt, Mrs. Alexander Bustard of Passaic, was shocked to read of Samuel’s death in the New York Daily News. Aware of his illness but perplexed why she did not hear of his death from Camp Dix officials, she immediately telephoned the base hospital. “The message that came over the wire from the camp to Mrs. Bustard was to the effect that Sammy Bustard was recuperating from the effects of influenza and that he would soon be out of the institution.”[74]

The Morning Call added, “Bustard was very ill with the sickness and for a long time his life hung in the balance; but his rugged constitution finally won the battle and he is now getting along nicely.”[75] Bustard was a lucky man – many young adults with “rugged constitutions” would lose their battles, as the Spanish flu’s “W-shaped” mortality curve would later reflect.

Post-war success with Morse and New York FC

Bustard, who was “too hard for the germs,” recovered enough to return home on furlough on November 1.[76] Ten days later the Armistice of 1918 was signed and in early December Bustard was discharged from the Army’s 153rd Depot Brigade. By Christmas, the lure of the shipyards proved too great and Bustard signed with the Morse Dry Dock FC, of Brooklyn. Bustard took a job as a “burner,” which was regarded as a dangerous profession due to its use of flammable compressed gasses. Always on the prowl, the Morse management took advantage of the “maelstrom of changing events” to sign several members of the Fall River Rovers, who did not organize for the 1918/19 season. They also added Connie Lynch, former Paterson True Blue star, and referred to by the Brooklyn Daily Times as the “peer of American soccer centre forwards.”[77] The acquisitions immediately transformed Morse into “one of the most dangerous teams in the vicinity of New York.”[78]

In an odd twist of fate, Paterson FC, Bustard’s old team, knocked Morse from both of the major cup competitions during the 1918/19 season. Paterson, bolstered by the additions of Archie Stark, Tommy Stark and Davey Brown, won the American Cup contest 5-1. Bustard missed the National Challenge Cup semi-final rematch on March 30, which Paterson dominated in a 4-1 win. Six ex-Fall River Rovers dressed for Morse that day.[79]

Bustard again represented Ireland in the 1919 NYFPA international series. Winners of the competition in 1918, the Irish lost 4-1 to Scotland in the 1919 semi-finals. Although the Sons of Erin were able to defeat the American squad, the Scots were too much with McKelvey, Miller, and Campbell from Bethlehem and Archie Stark from Paterson. McKelvey and Stark both delighted the crowd with goals scored by individual runs from midfield and beyond.[80]

Under secretary Wilfred Hollywood, Morse Dry Dock FC would rise from the local Metropolitan League to the Shipyard League and onto the NAFL for the 1919/20 season. Although they finished in a disappointing sixth position, they were now playing against the finest competition in the east. The Morse Dry Dock Dial commented that the “National Football League means just as much to the followers of that sport as the National League in baseball means to the baseball fan.“[81] Just as the Bethlehem Globe predicted, the founding of the “War Works” teams generated an unusually high level of competition – with weekly slugfests taking place between Morse, Bethlehem Steel, Robins Dry Dock, Paterson FC, Kearny Federal Ship, and Erie AA. The AFA Cup final was an all NAFL affair, with Robins narrowly defeating Bethlehem 1-0. Fore River, a Massachusetts shipyard team, represented the east in the National Challenge Cup competition, but the eastern final four consisted of three other NAFL clubs: Robins, Bethlehem, and the New York FC.

Morse Dry Dock FC disbanded in August 1920, the Boston Globe reporting “difficulty existing between the players and officials will cause the club to break up.”[82] Staying close to home, New York FC was Bustard’s destination for the 1920/21 campaign. With Bustard running the team from his center halfback position, the New Yorkers took second place in the NAFL behind Bethlehem Steel. New York ruined Bethlehem’s perfect season with an early November tie “before a record crowd at New York Oval.”[83] New York faced a tough first-round draw in the National Challenge Cup competition, losing to eventual Eastern finalist Tebo Yacht Basin FC.

The 1920/21 season was owned by Robins Dry Dock, who went on to capture both the AFA and National Challenge Cup competitions – a feat only accomplished to that point by Bethlehem Steel. The Boston Globe’s George Collins wrote that Robins was “the best team we have had come to Quincy for years” after they easily dispatched Fore River in the National Challenge Cup competition.[84] The forward line of Robert Hosie, Pete Sweeney, Harry Ratican, John McGuire, and George McKelvey was hard for any team to handle, with Hosie and Sweeney making an unusually potent left wing. Robins failed to win the “treble”, however, Tebo gaining a measure of revenge by knocking off Robins in the final of the Southern New York State Football Association Cup.[85]

The haves, the have-nots, and the American Soccer League

Professional soccer in the northeast was changing at a drastic pace. The First World War had successfully purged smaller NAFL clubs such as Newark FC, Jersey AC, Scottish-Americans, and the West Hudsons, and the survivors were clubs with large bankrolls backed by shipyards or wealthy businessmen. Even established clubs could be gone in a matter of months, as exhibited by Paterson FC. Although a successful club in its three brief years of existence, Paterson resigned from the NAFL in January 1921 due to poaching from the shipyard clubs and “many of its best players deserting to join the Erie AA.”[86] Most teams now resembled the “All-Star Aggregations” seen many years prior, and these lineups were expensive. The level of play was high, and games between New York FC, Robins, and Erie AA would commonly attract over 4000 – 5000 spectators, generating large gate receipts. So large, in fact, that the AFA stepped in to try to end the series of deadlocks between Robins and the Eries during the 1920/21 cup competition. Levi Wilcox of the Philadelphia Inquirer observed, “it is evident that the players of the Erie and Robins teams are looking for the long end of the gate receipts rather than the honor of winning the American Cup.”[87]

The 1920/21 NAFL season would be a case of the haves and the have-nots – Bethlehem Steel, New York FC, Robins Dry Dock and the Erie AA at the top – and Babcock & Wilcox, Philadelphia Disston and the grossly overmatched Bunker Hill FC of Paterson at the bottom. The mediocre performance of Robins and Erie in the NAFL regular season made it painfully obvious the clubs valued high-grossing cup contests over NAFL play. It was clear these “super clubs” had outgrown the NAFL and, fortunately for them, Thomas Cahill had an idea.

The Fall River Globe reported on April 11, 1921, “the organization of a circuit of professional soccer football clubs in Eastern States has reached concrete form, according to a statement made yesterday by Thomas W. Cahill of New York City, secretary of the United States Football Association.”[88] The league, to be known as the Inter-State Soccer Association, would consist of an Eastern and Western Circuit. “At the conclusion of each season it is intended to have a series of three or five games played between the winners of each circuit to decide the National championship.” The grand plan only included sketchy details of the proposed Eastern circuit, which included teams from Philadelphia, New York, Brooklyn, Harrison, Jersey City, Fall River, and Pawtucket. A reorganized Bethlehem Steel Club reportedly would also take part. The plans changed slightly, however, and on May 9 the announcement of the new American Soccer League (ASL) took place during a meeting at the Hotel Astor, New York. The clubs identified for the new league included the New York FC; Todd Shipyards FC of Brooklyn; Erie AA of Harrison, NJ; Celtic FC of Jersey City, NJ; Bethlehem Steel FC of Bethlehem, Pa; Philadelphia FC; Fall River FC of Fall River, Mass.; and the J & P Coates FC of Pawtucket, RI. By the time the first ball was kicked in September, Erie AA had been renamed Harrison FC and Bethlehem Steel FC was replaced by the Falco FC of Holyoke, Mass.

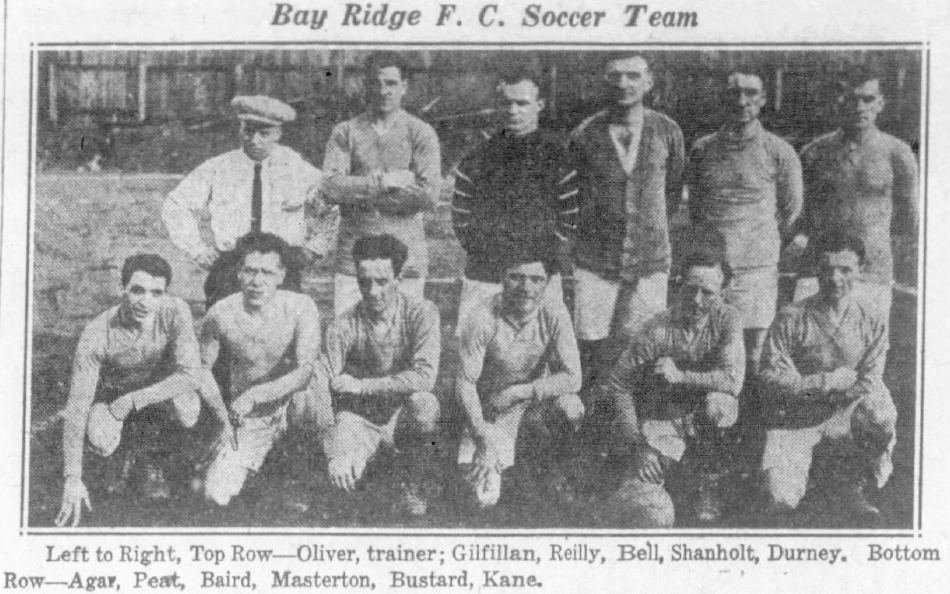

Samuel Bustard took part in the new venture with Harrison FC for the start of the 1921/22 season. Twenty-nine years old at the start of ASL action, Bustard featured in only six ASL contests and two National Challenge Cup contests for Harrison.[89] It is unknown why he left the Harrison eleven, but in January he was in action with the Bay Ridge club in the New York State League. The Brooklyn neighborhood of Bay Ridge, known as “Little Ireland,” fielded a strong team that featured several members of the Jersey City Celtic club that resigned from the ASL in December.[90] Also on the squad was Nathan Agar, soon to play a large role in the ASL with the Brooklyn Wanderers, and Harry Shanholt, professor of mathematics at Columbia University and winner of the inaugural National Challenge Cup in 1913 with the Brooklyn FC.

East versus West

In the spring of 1922 Bustard received an invitation to join an Eastern All-Star aggregation assembled to play a select team from St. Louis. The contest was conceived after the National Challenge Cup final in St. Louis, where Todd Shipyard was defeated 3-2 by St. Louis-based Scullin Steel. Harry Ratican, the St. Louis born star of the Todds, had returned to St. Louis for the cup final with much fanfare. Attempting to benefit from the enthusiasm generated by the final and the rivalry between St. Louis and the east coast clubs, St. Louis soccer officials tried to arrange a contest with two of the popular eastern teams, Harrison and New York of the ASL. St. Louis papers even went as far as saying Harry Ratican was under-appreciated at Todds because “Harry happened to be born in St. Louis instead of in England, Scotland, or Sweden.”[91] During his visit Ratican was involved in a March 26 benefit game for his brother Pete, manager of the Ben Miller squad, who was recovering from the effects of “a recent nervous breakdown.”[92] The benefit featured two teams, “the Bradys” – essentially the Scullin Steel team captained by Tate Brady – and “the Foleys” – largely composed of Ben Miller players.[93] Harry Ratican obtained a leave of absence from the Todd Ship team for the event and appeared at center forward for the Foley team in the second half, which ended as a 3-1 victory for Team Brady.[94] St. Louis officials were unsuccessful in securing one of the ASL clubs, so Ratican agreed to assemble a squad to represent the east.

The St. Louis Star and Times reported it was Ratican’s “object to get young and comparatively fast men, who will be able to successfully combat the typical St. Louis game, with which Ratican himself is familiar.”[95] The chosen few included goalie Gerald Cunningham, of Harrison; fullbacks Dick Spaulding and James Ingram, both of Harrison; halfbacks Sammy Bustard of Brooklyn, Neil Clarke of Todd Shipyard (captain), and Thore Sondberg of Fall River; and forwards Bart and Jim McGhee of the Philadelphia Hibernians, Harry Ratican of Todd Shipyards, Rudy Hunziker of New York FC, and Bobby Morrison of Bethlehem. Tommy Florie of Harrison, who later found fame as captain of the 1930 United States World Cup team, was brought along as a substitute.

The St. Louis All-Stars went on to win the game 3-0. The Globe-Democrat wrote, “Harry Ratican’s selected and carefully culled soccer stars played together as though they had grown up on the same playing field.” As was typical of the East/West showdowns of this time period, it appears the East stars held the possession advantage, and “outplayed the local men at every angle except shooting goals.” Ingram and Spaulding of Harrison had a fine game and Neil Clarke “came up to expectations, and perhaps surpassed to an extent.” Bustard, however, may have had a rough afternoon. “Joe McCarthy, who was forced to play very clever football to elude Sammy Bustard, the opposing half back, drove through two early goals in the second half.”[96] The St. Louis stars rounded out the scoring when Allie Schwarz, scorer of the game-winning goal for Scullin Steel in the National Challenge Cup, scored off a feed from McCarthy.

A career ends in Brooklyn

After his return from St. Louis, Bustard had a brief association with the Brooklyn Wanderers, run by ex-Bay Ridge teammate Nate Agar. Bustard had several appearances with the Wanderers, making his debut and playing “a heady game at center half” against the Paterson Caledonians on October 29, 1922.[97] He participated in the Wanderers’ National Challenge Cup competition loss to Brooklyn FC on November 6, but in late November the Daily News reported the decision by the “American Soccer League moguls” to award a franchise to Agar’s Wanderers. Although Bustard was listed as a professional on the club’s roster, Samuel left the Wanderers shortly thereafter to join Emerald Celtic FC in the second division of the New York State Soccer League (NYSL).[98]

New York soccer in the 1920s was booming and truly cosmopolitan in nature. A 1924 benefit game between a picked eleven from the Southern New York State Football Association and Brooklyn FC included in the lineup players from Hungaria in the Metropolitan League, Hispano FC in the Spanish League, Swedish FC in the Brooklyn League, and Germania and Manchester Unity in the Empire State League.[99]

Over in Brooklyn, soccer experienced a strong period of growth in the 1920s bolstered by forward-thinking league officials and fan exposure to multiple tiers of quality soccer – from the Wanderers in the ASL to the various second-tier leagues such as the Brooklyn Soccer League (BSL). The goal of developing native talent and creating a pipeline from high school to the various amateur and professional leagues was cultivated at a grassroots level. The BSL announced plans in 1925 to expand to two divisions, incorporating a junior league composed of Boy Scout teams and “former members of the various high school soccer teams.”[100] This approach was endorsed by the Brooklyn Wanderers, who “adopted the policy of admitting any member of the athletic association of the high schools or recreation centers, not over 21 years of age, to all the games at Hawthorne Field, Hawthorne Street, and Brooklyn Avenue, for a nominal sum.” The Wanderers would in return contribute five cents of each fee to the school, “to be used for soccer activities. “[101]

Bustard finished his career in this fertile Brooklyn soccer environment, playing for various teams associated with the Brooklyn Irish community – Emerald Celtic of the NYSL (1922/23), Brooklyn Hibernians of the BSL (1924/25) and finally St. Mary’s of the BSL (1925/26). Now over 30 and perhaps contemplating retirement, Bustard was inactive during the 1923/24 season before joining the Brooklyn Hibernians in late December of 1924. Retirement came in 1926 after suffering an injury in a “bitterly fought” contest against Brooklyn Edison that clinched the BSL title for the St. Mary’s FC in April.[102]

Bustard lived in Brooklyn for over 40 years and retired as a shipyard worker. He settled down in the neighborhood of Sunset Park, a stone’s throw from his place of employment at Morse Dry Dock and in-between Brooklyn’s three main Irish neighborhoods: Bay Ridge, Windsor Terrace, and Park Slope. He suffered from poor health from his early 60’s onward and eventually passed away in 1959 at the age of 67.[103]

On October 15, 1938, Samuel Bustard’s unusual story was retold by the Passaic Herald-News in a nostalgia piece titled “20 Years Ago Today.”[104] Included in the account was his reported death in 1918 and subsequent recovery from the Spanish Influenza at Camp Dix. Bustard, however, was a survivor of more than just his bout with the killer virus. Coming to this country from Belfast as a 20-year-old, he clawed his way from a local amateur side in Paterson to an American Soccer League roster. He served his adopted country, raised a family, all while having a solid fourteen-year soccer career playing for many of the storied clubs of the era. Bustard persevered through the changing New York metropolitan area soccer landscape that contributed to the demise of long-standing teams such as the Paterson True Blues, Scottish-Americans, West Hudsons, and Brooklyn Celtics. Retiring after an injury suffered leading his team to a league championship, Bustard would leave as he started — bareheaded and with bleeding knees exposed to the winter’s chill.

Notes

[1] “Ireland Soccers Advance,” New York Herald, February 23, 1918, 13. The games are not internationally recognized international contests. The teams mentioned were unofficial national teams that played under the auspices of the New York Footballer’s Protective Association. Local players were selected and usually played for the nation of their birth.

[2] “Sammy Bustard Is Not Dead But Is Recovering From the Influenza,” Passaic Daily News, October 15, 1918, 2.

[3] “True Blues Meet Olympics,” Paterson Press, October 26, 1912.

[4] “True Blues Qualify For Second Round,” Paterson Morning Call, October 28, 1912.

[5] “Cup-Tie Contest At Willard Park,” Paterson Morning Call, November 5, 1912.

[6] “True Blues Won Over Olympics,” Paterson Morning Call, November 11, 1912.

[7] “Rangers Play At Brooklyn,” Paterson Press, November 16, 1912.

[8] “Rangers Win At Brooklyn,” Paterson Press, November 18, 1912.

[9] “Blues Too Fast For Rangers,” Paterson Morning Call, January 6, 1913.

[10] “National League Elevens to Play Soccer Football,” Newark Star, November 15, 1913.

[11] “Soccer Football News and Notes,” Paterson Morning Call, July 28, 1915, 3.

[12] “Soccer Plans of National League,” The Paterson News, July 14, 1914, 7.

[13] “True Blues Quit For The Season,” Passaic Daily News, January 16, 1915, 3.

[14] “Soccer Men Elect,” The New York Press, Monday, July 12, 1915.

[15] “Haledon Thistles Throw Up Sponge,” Passaic Daily News, Wednesday, December 8, 1915, 3.

[16] “The Silk Strike of 1913,” http://www.patersongreatfalls.org/silkstrike.html, Excerpt from the book The Fragile Bridge: Paterson Silk Strike 1913 by Steve Golin

[17] “Paterson Shy Not More Than 785,” The Record, August 6, 1915, 1.

[18] “Exhibitions By Soccer Elevens,” Newark Eagle, September 20, 1915.

[19] “Soccer Football Season Started,” Newark Eagle, September 13, 1915.

[20] “Bethlehem Wins,” Fall River Daily Evening News, April 3, 1916, 3.

[21] “West Hudsons are in Fourth Round,” The Newark Eagle, January 16, 1916; “Hudsons Finally Dispose of Yonkers Soccer Team,” The Newark Eagle, January 3, 1916.

[22] “Association Football: New York and New Jersey,” The American Cricketer, Volume XXXIX, No. 734, April 1916, ed. A.J. Henry (The Associated Cricket Clubs of Philadelphia), 116.

[23] “New York F.C. Out To Even Score With Morse Team,” The Standard Union, Brooklyn, N. Y., December 24, 1918, 8.

[24] “Celtics Take Soccer Cup,” New York Times, June 25, 1917, 12.

[25] “Bethlehem Downs Brooklyn Celtics,” Philadelphia Inquirer, January 7, 1917, 17.

[26] “Montclair Team Down Passaics,” Passaic Daily News, November 27, 1916, 10.

[27] “New York Footballers’ Protective Association,” Spalding’s Official Association Soccer Foot Ball Guide, 1912-13, ed. Thomas W. Cahill (New York: American Sports Publishing Company, 1912), 91-95.

[28] “Local Soccer Expert Highly Honored Today,” Passaic Herald-News, February 12, 1916, 8.

[29] “Local Players in Big Game,” The Paterson Morning Call, December 24, 1917, 3.

[30] “Passaic Player In Big Soccer Game,” Passaic Daily News, February 14, 1917, 5.

[31] “New Paterson Eleven Holds Bethlehem To Tie,” The Bethlehem Globe, November 5, 1917.

[32] “Business Men Face Seniors in Evening,” Passaic Daily News, December 29, 1917, 3.

[33] “Soccer Game at Olympic Park,” The Paterson Morning Call, September 15, 1917, 3.

[34] “Soccer Game at Olympic Park,” The Paterson News, September 15, 1917, 8.

[35] “Steel Soccer Eleven Loses,” The Bethlehem Globe, May 13, 1918 .

[36] Kempshall, Chris. “American Soldiers Arrive in France,” The East Sussex WW1 Project, www.eastsussexww1.org.uk/american-soldiers-arrive-france/index.html. Accessed 29 March, 2020.

[37] “Soccer Is Hit Hardest of All Sports by War,” New York Tribune, March 31, 1918, 21.

[38] “Soccer Player Killed,” Fall River Daily Evening News, November 1, 1916, 8. Other Newark F.C. players killed in battle included David Holmes, Robert Dunlop and George Battison.

[39] “Soccer Players Enlist in Army and Navy,” The Daily Standard Union, Brooklyn, August 14, 1917, 8.

[40] “Fall River Rovers Not Entered In National Soccer Competition,” Fall River Globe, October 2, 1918, 6.

[41] “Soccer Is Hit Hardest of All Sports by War,” 21.

[42] “Babs Withdraw From National Soccer,” The Paterson Evening News, September 19, 1919, 18.

[43] Joe Booth, “Soccer News,” The Bridgeport Telegram, October 8, 1918, 14.

[44] “Six Soccer Teams In National League,” The Philadelphia Inquirer, September 21, 1918, 12.

[45] “Rival War Work Clubs to Crowd Schwab’s Kickers,” New York Tribune, September 30, 1918, 11.

[46] “Sammy Bustard to ‘Kick Off’ To the Kaiser,” Passaic Daily News, April 24, 1918, 10.

[47] C. A. Lovett, “Shipyard Clubs Lure Star Soccer Players With Jobs,” New York Tribune, October 27, 1918, 16.

[48] “Soccer,” The Globe, Bethlehem, PA, July 31, 1918.

[49] C. A. Lovett, “Many Testify at Soccer Hearing on Tempting Players,” New York Tribune, December 10, 1918, 13.

[50] “Soccer in Camp Upton,” The Evening Post, New York, October 8, 1917, 6.

[51] “Championship Soccer Title May Go To Great Lakes Tars,” The St. Louis Star, October 11, 1918, 13.

[52] “Camp Devens Takes the Measure of Manufacturers’ League Team,” Fall River Globe, November 30, 2017, 6.

[53] “Harrison Field Scene of Final Soccer Match,” Newark Sunday Call, May 12, 1918, 17.

[54] Michael Shurkin, “Pandemics and the U. S. Military: Lessons From 1918,” https://warontherocks.com/2020/04/pandemics-and-the-u-s-military-lessons-from-1918/, Created April 1, 2020, Accessed on May 9, 2020.

[55] “1918 Pandemic Influenza: Three Waves,” The Centers For Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), https://www.cdc.gov/flu/pandemic-resources/1918-commemoration/three-waves.htm, accessed May 9, 2020.

[56] C. A. Lovett, “Army Move May Give Bethlehem Football Title,” New York Tribune, April 28, 1918, 22.

[57] “Soccer Notes,” The Globe, Bethlehem, PA, May 7, 1918.

[58] “An Epidemic of Influenza Threatens the Whole World,” The Wichita Beacon, July 6, 1918, 4 (from London).

[59] “If You Must Kiss, Filter the Smack.” The Boston Globe, August 17, 1918, 6.

[60] “Kiss Through Your Handkerchief,” The Ithaca Journal, August 24, 1918, 4.

[61] Byerly, Carol R. “Fever of War: The Influenza Epidemic in the U.S. Army during World War I.” New York, NY: New York University Press; 2005.

[62] “Dix Breaks Loose Over War Reports,” The Morning Post, Camden NJ, September 14, 1918, 7.

[63] “Protect Camp Dix Men Against Influenza,” The Philadelphia Enquirer, September 18, 1918, 2.

[64] John Kopp and Bob McGovern, “100 years ago, ‘Spanish Flu’ shut down Philadelphia – and wiped out thousands,” The Philly Voice, https://www.phillyvoice.com/100-years-ago-spanish-flu-philadelphia-killed-thousands-influenza-epidemic-libery-loan-parade/, created September 27, 2018, Accessed on May 15, 2020

[65] Ed Farnsworth, “Philadelphia Soccer and the 1918 Spanish Flu Epidemic.” Society for American Soccer History, accessed June 15, 2020. https://www.ussoccerhistory.org/philadelphia-soccer-and-the-1918-spanish-flu-epidemic/

[66] Joe Booth, “Influenza Scare Interferes with Soccer Contests,” The Bridgeport Telegram, October 15, 1918, 16.

[67] John M. Barry, The Great Influenza: The Story of the Deadliest Pandemic in History (New York: Penguin Books, 2005), 249.

[68] C. A. Lovett, “’Flu’ Lays Low Start of Soccer Title Matches,” New York Tribune, October 13, 1918, 21.

[69] “Champion Olympics – They Win the American Cup and Medals,” Fall River Daily Herald, April 23, 1894, 6; “True Blues, Hurrah,” The Paterson News, April 20 1896, 6; “Sporting Variety,” Fall River Daily Herald, November 12 1894, 7; “A Lantern Parade,” The Paterson Morning Call, October 9, 1894, 1.

[70] “Soccer Player Dead,” New York Tribune, October 14, 1918, 15.

[71] “Sammy Bustard Dies At Camp Dix – A Victim Of Epidemic Influenza,” Passaic Daily News, October 14, 1918, 3.

[72] “Soccer Games Postponed,” The Philadelphia Inquirer, October 14, 1918, 12.

[73] “Soccer Expert At Death’s Door,” The Daily News, New York, February 4, 1923, 132.

[74] “Sammy Bustard Is Not Dead But Is Recovering From the Influenza,” 2.

[75] “Soccer Football News and Notes,” The Paterson Morning Call, October 17, 1918.

[76] “Sammy Bustard Is Home On Furlough,” Passaic Daily News, November 1, 1918, 3.

[77] “Bethlehem Soccers Again Put Off Game with Morse,” The Brooklyn Daily Times, October 16, 1919, 8.

[78] “Morse Eleven Triumphs, 4 To 0,” Fall River Daily Evening News, October 21, 1918, 3.

[79] “Paterson Trims Morse Dry Dock,” Fall River Globe, March 31, 1919, 9.

[80] “Irish Team Dropped Game To Scotland.” Passaic Daily News, May 5, 1919, 3.

[81] “We Join National League,” The Morse Dry Dock Dial, September 1919, 15.

[82] “Soccer Snaps,” The Boston Globe, August 9, 1920, 7.

[83] “Bethlehem Held To Tie At Soccer,” New York Herald, November 1, 1920, 10.

[84] “Robins Soccer Team Best Yet Seen Here,” The Boston Globe, March 7, 1921, 6.

[85] “Tebo Soccers Beat Champion Robins,” The New York Times, May 16, 1921, 19.

[86] “Patersons Throw Up the Sponge”, The Morning Call, Paterson, NJ, January 4, 1921, 3. The Paterson F.C. would be replaced I the NAFL by the Bunker Hill FC, also of Paterson.

[87] “Soccer Players Owe Duty to the Public,” The Philadelphia Inquirer, April 4, 1921, 13.

[88] “Fall River in Soccer League,” Fall River Globe, April 11, 1921, 8.

[89] Colin Jose, American Soccer League, 1921 – 1931: The Golden Years of American Soccer (Lanham, MD: Scarecrow Press, 1998), 33.

[90] “Crack Soccer Players in Indoor Contest”, The Standard Union, Brooklyn, NY, March 24, 1922, 19.

[91] “Hosie of Todd Team Is One of Greatest Forwards of Game,” The St. Louis Star and Times, March 17, 1922, 21.

[92] “Harry Ratican May Succeed Brother as Leader of Millers,” The St. Louis Star and Times, March 19, 1922, 37.

[93] “Arrangements Complete For Pete Ratican Benefit Sunday,” The St. Louis Star and Times, March 24, 1922, 22.

[94] “Bradys Beat Foleys; Harry Ratican Plays,” The St. Louis Star and Times, March 27, 1922, 15.

[95] “St. Louis Eleven and Pick Of East Meet Tomorrow,” The St. Louis Star and Times, April 1, 1922, 11.

[96] “St. Louis Soccer Team Defeats All-Star Eleven from the East, 3 to 0,” St. Louis Daily Globe Democrat, April 3, 1922, 9.

[97] “Wanderers Beat Paterson; Retain Lead in the League,” The Brooklyn Daily Times, October 10, 1922, 12.

[98] C. A. Lovett, “Wanderers Land Brooklyn Berth In Soccer League,” Daily News, New York, New York, November 19, 1918, 22.

[99] “Crack Soccer Teams Will Play Benefit Game,” The Brooklyn Citizen, December 12, 1924, 8.

[100] “Soccer League To Develop Native Talent,” The Brooklyn Daily Eagle, July 1, 1925, 23.

[101] “Encourage Schoolboy Interest in Soccer,” The Standard Union, Brooklyn, N. Y., January 1, 1926, 15.

[102] “St. Mary’s Churches’ League Championship,” The Chat, Brooklyn, N.Y., April 10, 1926.

[103] “Samuel Bustard, Shipyard Aid,” The New York World Telegram and Sun, July 2, 1959, B4.

[104] “20 Years Ago Today,” The Herald-News, Passaic, New Jersey, October 15, 1938, 9.

Fantastic work, Kurt! Very well structured and very telling in these COVID-19 days.

I read an early version of this post and it was mesmerizing in its depth of research, plus it rings so true in our current times. So glad that Kurt Rausch has shared it with all here. It’s a great example of how the history of soccer can be told through an individual life. Bravo!