The history of soccer in Philadelphia is long and rich, but it cannot be told without some understanding of football’s prehistory. The 13 original Laws of the Game, approved at the Freemason Pub in London on Dec. 8, 1863 — and which form the basis of association football, or soccer — were a first step in the codification of the evolution of football games that had been a part of British cultural life for centuries. The football-rich history of Britain meant that early British settlers in Philadelphia brought football with them. But they brought football to a land whose original inhabitants already had their own versions of the game. And so, the first football players in America were the Native Americans.

But the football games played by Native Americans and Philadelphia’s early European settlers were not soccer. Indeed, even after 1863, years would pass before the continuing evolution of the Laws of the Game would result in a sport that resembles soccer as it is played today.

Early football games in Britain

Football’s recorded history in Britain stretches back to the Roman occupation, which began in 43 CE. But, as British football historian Percy Young describes, when the Romans brought the game of Harpastum with them, “It may be assumed that those of the Britons and Celts who then made up the native population were, from time to time, involved in the Roman game. At the same time it may safely be assumed that the native population had evolved their own kind of ball-play, just as when English colonists desirous of exporting football to America found that the indigenous Indians had a football game of their own already firmly established.”

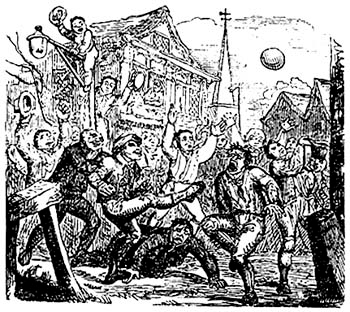

Accounts of “a game of ball” can be found in Nennian’s Historia Britoniam, written in the ninth century before the Norman Conquest. A more precise description from 1175 recounts an example of Shrovetide football. That football was commonplace in early medieval England is evidenced by the number of contemporary legal documents, court cases, and denunciations of the game. The reasons for this are simple: football could be extremely violent and result in serious damage to property, as well as injury and even death for its participants. Thus, football for many represented a clear threat to public order. This could only be because football, whether it was the country football of rural towns or the street football of emerging urban areas, had become a recurrent and popular fixture of British folklife.

Numerous royal, municipal, and ecclesiastical proclamations restricting or banning the game were issued. Edward II banned the game as early as 1314. Further proclamations by Edward III, Richard II, Henry IV, Henry V, Edward IV, Henry VII, and Henry VIII give some idea about how ineffective such bans proved to be against so ubiquitous a pastime with such strong cultural roots. Royal proclamations against football were not restricted to England: James I banned football upon his return to the Scottish throne in 1423.

Provincial towns attempted bans between 1450 and 1650, often at the direction of royal decrees. Clergy were barred from playing football as early as 1364. But as with royal and municipal attempts to restrict football, the effectiveness of ecclesiastical bans was often in question: the Feast of St. Catherine the Martyr was celebrated with a game of football on the grounds on Bicester Priory in Oxfordshire during the 14th century. Young even suggests that the first professional football game took place on St Catherine’s Day (November 25), 1425 because the prior sanctioned the gift of four pence to the football players. The connection of football with religious holidays and feast days continues to the present day in traditional British Shrovetide games.

While football in Britain would experience repeated attempts to restrict its various forms until the formalization of standard rules in the mid 19th century, it would also move from its folk roots into higher culture with abundant references to it in the songs, poems, plays, literature, and memoirs of the day. This was not only because figures as diverse as Oliver Cromwell and Charles II either played or supported the playing of the game. Indeed, while on the football field, class differences might be forgotten, even at this early date. Pre-19th century football can thus be thought of an expression of emerging democratic values.

How the game was played

What might a game of football looked like in England before the codification of the Laws of the Game?

“Folk football” describes a wide range of local-based playing traditions and so no single set of rules can be described. In more rural towns, the playing area might be a mile or more long and encompass fields and streams as well as the town. In more urban areas, the field of play would be restricted by available green space, or a game might simply be played in the streets. The number of players participating would likely be restricted by the size of the playing area: hundreds of players per side or a few as ten, twenty or thirty. Hence such football being referred to as “mob football.”

A football game might pit town against town, married men against single men, or trade against trade. Teams could be dressed in the same color to identify themselves or they might wear the same hats. The players would more likely be young males because of the violence and risk of injury associated with the game. The goals might be a stream or tree, or some landmark in town. Scoring first might win a game, or a team might have to score a set number of goals or simply have the most goals at the end of the game, which might last all day with a break for food and drink. Short of outright murder, it seems that pretty much everything — kicking the ball, handling the ball, kicking and handling opponents — was considered fair play.

Perhaps the earliest account of how a football game was actually played comes from an account published sometime after Henry VI’s death in 1471:

The game at which they had met for common recreation is called by some the foot-ball game. It is one in which young men, in country sport, propel a huge ball not by throwing it into the air but by striking and rolling it along the ground, and that not with their hands but with their feet. A game, I say, abominable enough, and in my judgment at least, more common, undignified, and worthless than any other kind of game, rarely ending but with some loss, accident, or disadvantage to the players themselves…What then? The boundaries had been marked and the game started, and, when they were striving manfully kicking in opposite directions, and our hero had thrown himself in the midst of the fray, one of his fellows, whose name I do not know, came up against him from in front and kicked him by misadventure, missing his aim at the ball.

While the writer of this account describes the violence attendant to the football of the day, he also notes some important aspects of the game: it is an organized activity with two opposing sides, no use of the hands is allowed, and the field of play is clearly marked by boundaries.

Francis Willughby’s Book of Games, written around 1660 (Willughby died at the age of 36 before the book was completed), contains diagrams indicating the placement of goal markers. In addition to containing a proscription against kicking an opponent above the shin, it also included what might be the first primer on how to foul an opponent entitled “Tripping of Heels.” Using a ball made of an inflated bladder sewn into “the skin of a bull’s cod,” Willughby describes the game is played

in a long street, or a close that has a gate at either end. The gates are called Goals . . . The ball is thrown up in the middle between the goals . . . the players being equally divided according to their strength and nimbleness . . . players must kick the ball . . . and they that can kick the ball through their enemies goal first win. They usually leave some of their best players to guard the goal while the rest follow the ball.

Willughby gives us a description of the ball and the goals, describes efforts to make teams of equal strength for a more interesting match, specifies the requirement that the ball must be kicked, provides an idea of how a game was won, and relates the use positional players “to guard the goal.”

Willughby doesn’t provide a fixed number for how many players would be on each side but the description of players being “equally divided according to their strength and nimbleness” suggests an evolution away from the wild play associated with folk football to something more refined and “sporting.” A later example of this trend can be found in poem published in 1720 by the Irish poet Matthew Concannen called A Match at Foot-ball that describes a game of six-a-side.

Exactly what version of football was played by British colonists in Philadelphia would likely depend upon the moment as much as whatever version of the game was most familiar to them. Most likely, rules would shift according to who organized a particular game, who was playing, and where the game was being played.

Native American football

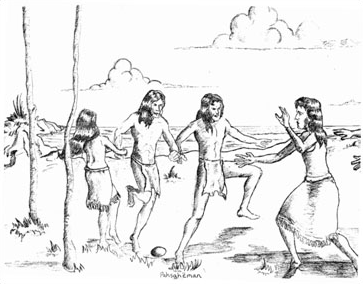

Accounts of Native American football can be found in the first histories of the Jamestown and Massachusetts Bay colonies. In some respects, Native American football games would be familiar to colonist who brought with them their own football traditions, with each side having scores, if not hundreds, of players engaged on massive fields of play that might be a mile or more in length, with melees featuring plenty of physical — if not physically damaging — contact, and different rules in terms of handling and/or kicking of the ball. As was the case back in Britain, how Native American football games were played varied.

Around Jamestown, the first Secretary of the Colony, William Strachey, wrote in The Historie of Travaile into Virginia Britannica (1612) of “a kind of exercise” among the Native Americans:

They have the exercise of Football, in which yet they only forcibly encounter with the foot to carry the Ball the one from the other, and spurn it to the goal with a kind of dexterity and swift footmanship, which is the honor of it.

In Relation of Virginia (handwritten manuscript published in 1872), Henry Spelman, who spent a year-and-a-half beginning in 1609 in bonded servitude with the Powhatan people in order to become an interpreter, describes, “They [the Virginia Indians] use beside football play, which wemen and young boyes doe much play at. The men never. They make ther Gooles as ours only they never fight nor pull one another doune.”

William Wood, who was an early settler on the North Shore of Massachusetts where Pasuckquakkohowog — “they gather to play football” — was played, wrote in New England Prospect (1634) with admiration of “the swift footmanship, their strange manipulation of the ball and their plunging into the water to wrestle for the ball,” but was disdainful of the Native Americans’ technique and tactics. Displaying what would come to be an all-too-familiar English arrogance about all matters football, Wood claimed “One Englishman could beat ten Indians at football.” Such contempt illustrates an important fact: while Native Americans had their own forms of football, their influence on the football played by early colonists in America was nil.

Although Philadelphia was founded in 1681, Dutch, Swedish, and English colonists had explored, traded, and farmed along the Delaware since 1609. There they encountered members of the Lenni Lenape or Delaware tribes.

The Lenapes had their own version of football, which was called Pahsahéman. Knowing exactly when the Lenapes began to play Pahsahéman is difficult: theirs was an oral tradition so contemporary accounts about their culture were written by Europeans who made little or no distinction between the various tribes in a given area.

Describing Delaware or closely related tribes that were living just north and east of the main body of Lenape, an account from 1656 says that “Their Recreations are chiefly Foot-ball and Cards, at which they will play away all they have, excepting a Flap to cover their nakedness.”

Some scholars have suggested that the Lenape learned their game of football from the Shawnee, who moved into Lenape territory near the Delaware River in Southeastern Pennsylvania beginning around 1692, but descriptive accounts of the football games of either tribe in that time period are sorely lacking. Existing accounts of Lenape football come from after they were pushed out of Southeastern Pennsylvania. Details of how Pahsahéman was played are thus based on accounts from Lenape who settled in Oklahoma or Ontario rather than those who lived in the area around Philadelphia.

Did early colonists in the Philadelphia area witness the Lenape playing football? Did they play football with the Lenape? As of this writing, I have not found accounts of either. While it seems likely that early settlers would have witnessed Native American football, the possibility that they engaged in football games with the Native Americans seems less so. Deciding what rules would govern the contest would be difficult given the language barrier. More to the point, the violent play inherent in the tradition of how the English played football meant there was the real possibility that a game could result in serious offense. Why risk inflaming the passions of a people who already had plenty of reason for grievance against European settlers?

Indeed, an account from Henry Morgan published in Richard Hakluyt’s The Principal Navigations, Voiages, Traffiques and Discoueries of the English Nation (1589–1600) of an football game in 1586 between Native Americans and British explorers before the beginning of permanent settlement in North America describes,

Diverse times they [Native Americans] did wave us on shore to play with them at the football, and some of our company went on shore to play with them, and our men did cast them down as soon as they did come to strike the ball. And thus much of that which we did see and do in that harbor where we arrived first.

What may have been the first international friendly in the New World wasn’t so friendly.

While we do not know if Philadelphia’s early British settlers played football with the Lenape, what is more certain is that the colonists brought their own games of football with them. However, carving a new civilization out of the primordial wilderness of the Americas meant little time for the playing of football — there was simply too much work to be done. Some colonists also brought religious ideas with them that made them look unfavorably upon such game playing, especially on Sundays.

Football games were thus likely to be infrequent in the early colonial period. As communities in colonies that were founded by religious orders such as the Puritans and the Quakers became more settled, and attitudes toward forms of leisure such as football were diluted by the arrival of new colonists from different backgrounds and traditions, games of football became more commonplace. When it was played, football followed the rough and violent style of play the colonists would have known back in Britain. Melvin I. Smith describes in Evolements of Early American Foot Ball (2008), “[B]y the end of the eighteenth century, the kicking game of foot ball was somewhat of a gang-fight centered around a ball.”

The playing of soccer football was still a long way away.

A version of this article first appeared at the Philly Soccer Page on November 17, 2014