The authors would like to thank Brian D. Bunk, Gabe Logan, and Tom McCabe for their advice and comments.

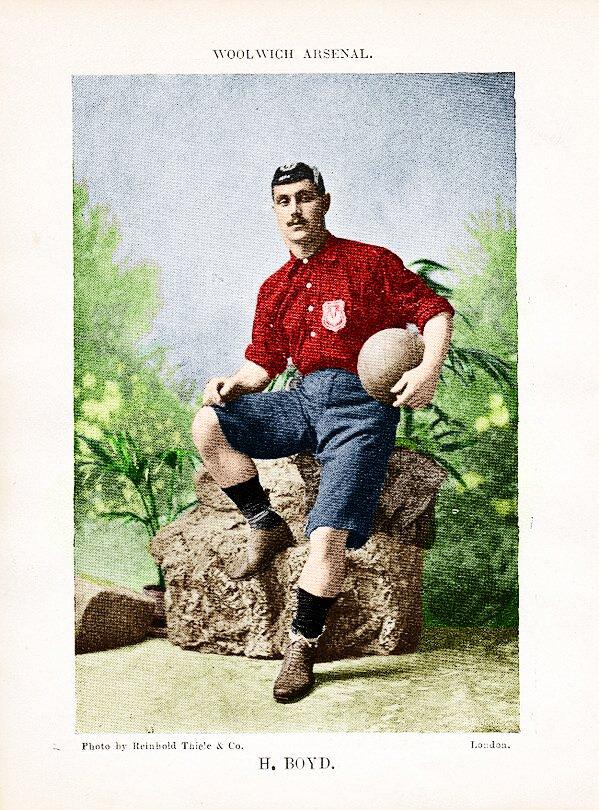

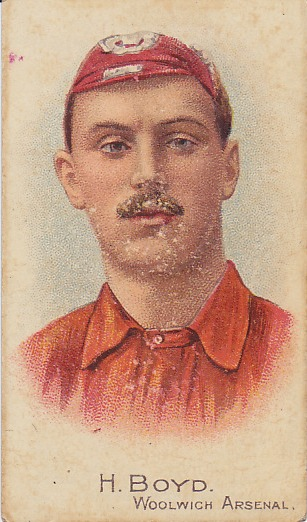

In an essay published in June 2018 at scottishsporthistory.com, Robert Bradley, Douglas Gorman, and Colin MacKenzie recount the career of the “talented but tainted” Scottish soccer player Henry “Harry” Boyd.[1] Boyd is perhaps best known for his time with Woolwich Arsenal, known today as the Premier League club Arsenal. With Arsenal he scored 32 goals in 40 league appearances between 1894-97, resulting in a goals-per-match percentage of 0.780 that remains the highest in the history of the club.[2] Boyd then moved to Newton Heath, the team that in 1902 adopted the name by which it is known today, Manchester United. With Newton Heath between 1897-99, Boyd continued his remarkable goal-scoring run, tallying 34 goals in 55 appearances, including 23 goals while appearing in all 30 league matches of the 1897-98 season.

That Boyd was talented is readily apparent. But his career was littered with repeated instances of injury, drops in form, leaving his club without permission, and violent conduct off the field. After the end of his playing career Boyd worked as a coal miner before dying in 1913 in a psychiatric hospital at the age of 44. Bradley et al. note the cause of death was listed as “general paralysis of the insane, a medical euphemism for the final stages of the sexually transmitted disease, syphilis.”[3]

Twenty years after his birth in 1869 in a coal mining village in Lanarkshire, Boyd first gained notice with the junior club Vale of Clyde FC in Glasgow. In 1890 he moved south to England to join Sunderland Albion. A center forward, Boyd scored 8 goals in 11 matches in league play in the Football Alliance, also scoring 1 goal in 3 FA Cup ties. In late January 1891, Boyd broke two bones in his foot in a match against Nottingham Forest.

In their timeline of Boyd’s life and career, Bradley et al. note that after his injury Boyd returned to Scotland, “his train fare to Glasgow paid by his club,” before sailing for America: “How he is able to afford his fare and how he spends his time overseas are not known.”[4] While in the US Boyd met former Burnley player Patrick Gallocher, who recommended he contact Burnley upon his return to Britain. This Boyd did, joining the club on August 8, 1892.

We can now reveal that Boyd settled for a time in the Chicago, Illinois area where he joined Chicago Thistle, playing for the club when it visited Fall River, Massachusetts, for a series of matches in September 1891. In December 1891, Boyd moved to Fall River, first joining Fall River Olympics, for whom he played in the Bristol County Cup and Mayors Cup tournaments. He also joined Fall River East End, with whom he played in the New England League and the American Football Association’s American Cup tournament. Before he left Fall River in July 1892 to return to England and sign with Burnley, Boyd appeared in 25 matches, scoring 17 goals in exhibition, league, and cup play. Along the way he helped his clubs win the Bristol County Cup, the New England League championship, and the American Cup, then the most prestigious soccer championship in the United States.

Boyd’s playing career in the US echoes that of his time in Scotland and England, a career marked by accomplishment on the field, trouble with his clubs, and violence off the pitch. His US playing career also illustrates the importance of the continuing influx of foreign-born players in the early history of the game in the US, the mobility of and competition for such players, and the challenges evident in the early stages of the professionalization of the game in the US.

Boyd with Chicago Thistle

Just when and where Henry “Harry” Boyd landed in the United States cannot be said with absolute certainty but a Henry Boyd departed from Glasgow as a steerage class passenger aboard the SS Manitoban on April 30, 1891, arriving in Philadelphia on May 14 after a voyage that included “a hard gale” and “terrific seas,” as well as a course change following the sighting of “an enormous iceberg.”[5] This Henry Boyd is listed as a 20-year-old stonecutter born in Ireland; the Scottish-born Henry “Harry” Boyd turned 22 the day before the Manitoban disembarked from Glasgow and the 1881 Scottish census listed then 12-year-old Henry as a “coal miner.”[6]

Whether or not the Henry Boyd who landed in Philadelphia aboard the Manitoban is the soccer player Henry “Harry” Boyd, the earliest newspaper reports possibly connecting him to Chicago Thistle began to appear in May 1891 in previews of matches against the Chicago Swifts and the Braidwood team, the first only two days after the Manitoban arrived in Philadelphia. In these previews, a Boyd (with no first name or initial) is listed at fullback, but no match reports have been located to confirm Henry “Harry” Boyd played in these contests. A Boyd appears again in a preview for another match against Braidwood in August 1891 and while positions are not specified the order of the names suggests Boyd at center forward. However, the Chicago Tribune match report published on August 17 does not include Boyd in the list of Thistle players who appeared in the game.[7]

While it is unlikely Henry “Harry” Boyd played for Chicago Thistle in the spring and summer following his arrival in the United States, the Braidwood connection is significant. Located about 50 miles southwest of Chicago, Braidwood at the time was a coal mining town, and home to many Scottish immigrant miners; the town’s name comes from Scottish engineer and mine operator James Braidwood (1831-1879). Soccer was a prominent sport in Braidwood in the 1890s, one supported by local coal companies who “laid out suitable playing fields” for their workers. One account described the Braidwood team as made up of “ten Scotchmen and one Belgian,” all of whom were “foreign born” save for the goalkeeper “who was born in Braidwood.” All but one of the players were miners.[8]

Braidwood’s Scottish mining connection may have been what brought Henry to the United States after his playing injury. Correspondence with Jillian Boyd, a distant relative of Henry’s now living in Australia, reveals generations of Boyds were coal, iron, and shale miners from the Scottish central lowlands in and around Glasgow.[9] As the coal industry in Braidwood and other nearby towns was developed, “experienced miners were recruited to come to Illinois, even being encouraged to immigrate from Scotland.”[10] The lure of a fresh start in the land of opportunity must have been great, and Henry’s older brother John emigrated to Braidwood in 1886 with his wife Annie. John may not have been alone, as further research suggests John’s uncle William also made the journey along with his wife, daughter, and son Colon.[11] Colon likely is the “C. Boyd” who played on the left wing for Braidwood in a January 2, 1891, encounter against fellow mining town Streator.[12]

Still a young man with undeniable talent on the football field, it is unlikely Henry “Harry” Boyd quit the game after his injury to become a full-time coal miner in Illinois. Soccer was an important means of community building in immigrant communities and was supported by some employers. More likely the Braidwood area offered Henry the perfect combination of a familiar profession, family contacts, and the ability to play competitive soccer. As we shall see, soccer would also provide Henry “Harry” Boyd an alternative source of income in the United States.

Boyd and Chicago Thistle visit Fall River

Chicago Thistle began play in 1888 and was composed, as its name suggests, primarily of Scottish immigrants. With ties to the railroad car manufacturer the Pullman Company and the “pride” of the Chicago Football Association, which itself was founded in 1886, Thistle was a dominant team, winning the league championship seven times, including an unbroken run of five championships between 1892 and 1897. Chicago soccer historian Gabe Logan describes an important component of the club’s success was its ability “to attract new immigrants who allowed them to keep abreast of playing changes in Britain, to secure top talent, and to dominate the Chicago league and showcase the city’s game when they traveled.” [13] Henry “Harry” Boyd was one such immigrant.

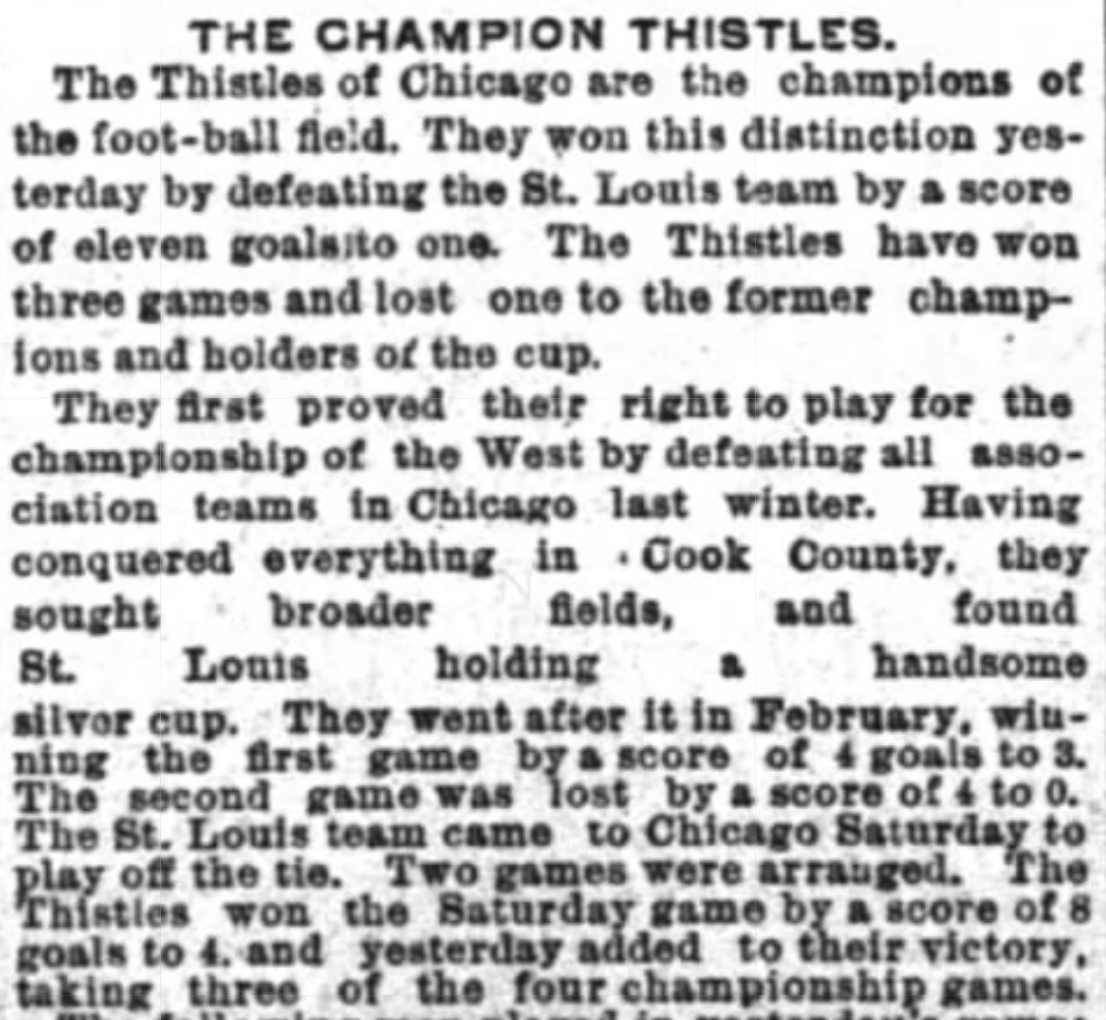

The first report clearly identifying Boyd with Chicago Thistle appeared on September 7, 1891, when the Chicago Tribune reported, “Harry Boyd, the new full back of the Thistles is a fine player and a tower of strength to his team.”[14] The report also noted Thistle was “training hard for their trip East.” This was a reference to the Thistles’ impending trip to play in Fall River, Massachusetts. Long distance travel for exhibition matches or inter-city championships was not a new endeavor for Chicago teams or, indeed, for other early centers of soccer in the US. A picked Chicago side visited St. Louis in 1890 for matches to determine the “amateur football championship of the West.”[15] Chicago Thistle visited the Mound City in March 1891, winning one game of a two-game series before defeating an all-St. Louis side in two return fixtures at home to win the “championship of the West.”[16] In May 1891, the first international trip by a Chicago soccer team took place when Chicago Cricket Club visited Canada for two matches.[17]

But the trip to Fall River was on a different scale of both distance traveled and ambition. Early reports described the Thistles planned matches in Toronto and Berlin (now Kitchener) in Canada, with US matches in Detroit, Pittsburgh, Fall River, Pawtucket, Brooklyn, Harrison, Trenton, and Philadelphia.[18] In reality, the tour involved matches only in Detroit and Fall River. Nevertheless, as Logan notes the Thistles’ visit “could rightly claim to be the first meeting of East and West soccer in the United States.”[19]

Fall River was at the time perhaps the most accomplished soccer scene in the United States, one featuring a mix of native-born and immigrant players and enjoying robust fan support with match attendance regularly reported in the thousands. Fall River clubs participated in multiple local and regional competitions: the Mayor’s Cup, open to clubs within Fall River; the Bristol County Cup, open to clubs from within the county Fall River was a part of; the New England League, which included clubs from Massachusetts such as those in Fall River and also clubs from neighboring Rhode Island, home to clubs from Pawtucket and Providence; and the American Football Association’s American Cup tournament. Founded in 1884, the American Cup was a knockout tournament modeled after England’s FA Cup. At first only featuring clubs from Northern New Jersey and New York City, the entry of New England sides beginning in 1887 allowed the tournament to better live up to the kind of hyperbolic language common in the sporting press of the day that declared the American Cup winner to be the champion of the United States.

Fall River sides had won the tournament every year since the 1887-88 edition and this success made the city a desirable destination for visiting domestic and Canadian sides. Fall River players also featured on the All-AFA team that visited Canada in 1888 and the Rovers visited Canada in 1889 before an All-New England League side followed in 1891. Area players also represented the US on the Canadian American team touring the UK at the time of Chicago Thistles’ East Coast trip. This prominence also made Fall River a popular destination for players already in the US at the time, such as the ex-Scottish International Neil Munro, who left the Newark Caledonians to join the Pawtucket Free Wanderers in 1890. Munro’s time with the Free Wanderers was brief. Selected to be a part of the 1891 Canadian American tour of the UK, he abandoned the tour in November, “having been persuaded by a Scotch club, Abercorn, to desert and play with them.”[20]

Chicago Thistle began their 1891 tour in Detroit, losing 2-1 on September 16 to Detroit FC at the Olympic Athletic Club grounds. The Chicago Tribune reported Boyd, who played fullback, “did some grand playing, but he wasn’t supported as he should have been.”[21] Boyd’s reputation preceded him in Fall River for the next day, a preview of the Thistles’ first match against Fall River Olympics on September 19 related, “The latest and most important addition to the team is Harry Boyd, a back, who is considered the best who ever left the other side to accept a position with an American club.”[22]

The journey to Fall River after the opening match on September 16 was no easy affair. Following two days of travel by rail from Detroit and an overnight voyage by ship from New York City (with expenses paid by the Olympics), the Chicago team landed in Fall River the morning of their first match. After checking into their hotel, the Thistles were driven around the city in a tally-ho coach to see the sights accompanied by members of the Olympic team and a brass band before arriving at the Fall River Olympics’ grounds.[23] The teams then played to a 3-3 draw in front of 1,500 to 2,000 spectators. Boyd, who started the match at fullback, moved to his customary center forward position at the start of the second half, tallying the final goal to level the scoreline. The Fall River Evening News reported, “The right fullback, Boyd, who played in the forward line for the Sunderland Albions, of England, last year, was sent to the front to do some rushing, and how well he did it the almost continuous cheering was an indication.” This shuffling between fullback and center forward would be a feature of Boyd’s playing time in the US. The same report said Boyd’s skill “towered above” many of his Chicago teammates.[24]

Boyd remained at center forward for the Thistles’ two final matches in Fall River, scoring twice in the 6-5 win over Fall River Rovers on September 24 and once in the 4-0 win over the Olympics on September 26. Match reports are filled with glowing praise for Boyd, who was described as “a player without equal” and “without a doubt the strongest in this country and probably the world.”[25] In correspondence after the tour the Thistle manager began referring to his club as “Champions of America.”[26]

Curiously, Boyd appears in no match reports for the Thistles after the Fall River trip. One reason for this may be a rule enacted by the Chicago Football Association in October 1891 requiring players to reside within 25 miles of the city to be eligible to play in association sanctioned matches.[27] Thus, if Boyd was living with his brother in Braidwood, he would’ve been ineligible to appear for Chicago Thistle. But the question of Boyd’s eligibility to appear for Thistle soon became moot.

Boyd moves to Fall River

On December 10, the Fall River Evening News reported on Boyd’s imminent arrival to join the Olympics, noting the Fall River team had “forwarded his fare.”[28] Subsequent reports indicated Boyd had signed with the Olympics to compete in the Bristol County Cup tournament. While the Olympics had won the 1889-90 American Cup, the team currently was “not strong financially” and probably unable to afford to pay Boyd to play for them in all competitions.[29] Soon, it was reported Boyd had also turned down an overture from Fall River Rovers, accepting instead “a big offer” from Fall River East End to feature for them in the American Cup tournament. Boyd received a tidy sum to sign with the East Ends, “the consideration being variously estimated at from $30 to $50,” or $887 to $1,479 in today’s value.[30] This signing bonus would have been in addition to whatever fee (and travel expenses) he received from the Olympics. For the sake of comparison, Bradley et al. note Boyd received “a £5 signing on fee” when he joined West Bromwich Albion in October 1892, the equivalent to about £652 in today’s value, or about $899.[31] Thus, the signing bonus Fall River East End paid Boyd equaled or exceeded what he later received in England. Even before the controversies of the American Soccer League “stealing” players from Scotland in the 1920s, the US clearly offered a financially attractive option for some international players.

On December 24, 1891, Boyd made his debut for the Olympics in a Bristol County Cup match, facing off against his other new club, the East Ends. Playing “his first game in three months,” Boyd scored the third Olympics goal to give his side a brief lead in the match, which finished as a 3-3 draw.[32] On January 2, 1892, Boyd made his American Cup debut for the reigning champion East Ends in a second-round matchup against the Fall River Rovers, winners of the 1887-88 and 1888-89 editions of the tournament. After starting at center forward, Boyd was moved to fullback when the Rovers scored two early goals. In the second half, Boyd scored the first East End goal of the day and then the winning goal in a match that finished 4-2 in favor of the East Ends.[33]

On January 8, Boyd was included in the roster of Olympic players registered to play in the Mayor’s Cup tournament.[34] Meanwhile, Boyd appeared for the Olympics in New England League and Bristol County Cup play. But an exhibition match against the East Ends scheduled for January 30 was called off due to dissension within the Olympics’ ranks. Boyd was at the center of the dispute.

Boyd is a professional in Fall River

Leading Fall River sides such as the East Ends, Olympics, and Rovers, as well as the Free Wanderers in nearby Pawtucket, had for several years fielded sides that were what would now be called semi-professional. Competition between the clubs for quality players was strong. One New Bedford player explained,

Whenever a player arrives here and shows any sign of ability the Fall River clubs will offer him such inducements as will make him go to the border city…In Fall River when it is learned that a player is to come to this country from England, the club managers get him a good job in some mill and thus secure him permanently. Then again the players there get regular pay for training, and a portion of the gate receipts. The clubs there are well backed with money and can do whatever they please to prosper the game.[35]

Enjoying comparatively strong financial backing, Fall River clubs actively searched for new players, both domestically and internationally. In addition to paying travel expenses and offering signing bonuses as we have already seen in the case of Boyd, desirable players could also be offered a secure job (one that necessarily included the flexibility to allow a player time off when needed for soccer-related activities), paid training, a weekly stipend, and a cut of match receipts. A cut of the gate could be a valuable source of income. For example, attendance at the Christmas Eve match between the Olympics and East Ends was reportedly between 2,000-3,000. Multiplying the low number with admission costing 15 cents results in a gate of $300, or approximately $8,875 today. Even after accounting for expenses what remained to be divided among the players was not insignificant. In a city where the average yearly earnings in 1890 was $329.74, or about $6.34 a week, it is reasonable to conclude a player could receive the equivalent of several weeks’ wages for playing 90 minutes of soccer.[36]

Unsurprisingly, jealousies could arise over the unequal distribution of pay, and that is the case here with Boyd and his Olympics teammates. One report said the dissension in the Olympics ranks was the result of “paying some players more than others,” noting, “This is not the first time that the importing of players has caused trouble in local teams.”[37] Another report observed “two of the Olympics have been receiving more pay for their services than the others in the eleven, and that the latter were disposed to raise objections when they found out the truth.” While the team nearly disbanded as a result, eventually “things were partly straightened out” and the team agreed to continue playing.[38] One result of this straightening out seems to have been Boyd’s appearance before a meeting of the New England League to request his release from the Olympics – but only for New England League fixtures: “he is perfectly willing to stick to the Olympics in other cup games.” Having decided “they could not afford to pay Boyd,” the Olympics readily granted his release.[39]

The East Ends and Pawtucket Free Wanderers now were in open competition to secure Boyd’s services for New England League play. The Free Wanderers announced on February 6 that Boyd would play for them in an exhibition match that day against Fall River Rovers featuring players recently returned from the Canadian-American tour of Great Britain. But Boyd did not play and after the match it was reported his “terms were so high that at the last moment the management decided to let him go.” Reports on February 8 said he had signed with East End, with whom he was already registered for American Cup play.[40]

Controversies surround Boyd

On February 11, the Fall River Daily Herald reported former Burnley and Brooklyn Longfellows forward Patrick Gallocher had arrived in Fall River to join the East Ends to play “in all the games except the cup ties.”[41] As Bradley et al. describe, it was Gallocher who connected Boyd to Burnley. But Gallocher’s presence in Fall River also underscores again the mobility of quality players in the US soccer scene at this time – and the willingness of clubs with the means to do so to pay them. Boyd and Gallocher played two matches together – Boyd at fullback and Gallocher at center forward – before Gallocher disappears from East End match reports. A report on April 11 said Gallocher “had left the city” and was now playing for New York Thistle, his third US club of the 1891-92 season.[42] Gallocher’s exit was not on the best of terms. On May 2 the Fall River Daily Herald reported the East End management “would like nothing better than to lay their hands” on the player nicknamed “the Artful Dodger,” adding, “They claim that he not only played in the team, but that he also played them.”[43] With clubs in open (and largely unregulated) competition for talent it is hardly surprising some players were perceived as unscrupulous or acting in their own self-interest.

In February through April 1892, Boyd appeared for both the Olympics and the East Ends. In a Bristol County Cup match on February 20 against the Rovers, Boyd was ordered off in the first half for fighting but refused to leave the field, a not uncommon incident that highlights the uncertain authority of match officials during this period of soccer’s development in the US. Boyd scored the lone Olympic goal in the 3-1 loss, but the match was called before full time after a pitch invasion followed another fight between players and police were unable to clear the field. Boyd was later censured by the Bristol County Football Association for “rough play” and the association soon incorporated a new rule sanctioning any player who refused to leave the pitch.[44] Over the same period, Boyd appeared for the East Ends in exhibition matches and also the American Cup semifinal on March 26. Playing fullback, his team defeated Fall River Conanicuts 4-1 in front of 6,000 spectators to advance to the final.[45]

Soon after the semifinal, Boyd was the focus of another controversy when the East Ends fielded him against the Rovers on April 7 in the opening Mayor’s Cup match, a humiliating 5-0 loss in front of 4,000 spectators. While not involved in the match, the Olympics immediately filed a protest against the East Ends’ use of Boyd in a Mayor’s Cup match. The East End management asserted Boyd was eligible to play for them in the Mayor’s Cup because he was signed for the team for the New England League; the Olympics claimed he was signed with them for the city tournament. Meanwhile fans were “getting disgusted” with the East End management “at the way they have been acting in the different leagues this season.”[46] Unable to reach a decision, the administrators of the Mayor’s Cup put the question of Boyd’s eligibility before a special jury of local sports journalists. On April 21, the journalists sided with the Olympics although they admitted, “In justice to Boyd it seemed to be too bad to prevent him from playing with the club that is willing to pay him for his services”. [47] Such eligibility disputes were commonplace in an era of weak governing bodies of limited jurisdiction and power. On April 30 just days after the eligibility decision, Boyd was at center forward for the East Ends in a New England League match against the Olympics, scoring the equalizer to make it 1-1 in what finished as a 6-3 victory for the East Ends.[48]

With the season drawing to a close, Boyd had to make decisions about what club to play for when match schedule conflicts began to arise – decisions that were no doubt made easier with “inducements” from the club that most needed his services. For example, Boyd scored the opening goal for the East Ends in a 4-0 road win over Pawtucket Free Wanderers in a New England League match on May 7, the same day the Olympics defeated Fall River Clippers 6-1 to clinch the Bristol County Cup. The Free Wanderers were a quality opponent in a league competition that was still to be decided while the Clippers were a weak opponent in a cup tournament essentially already won by the Olympics. The win in Pawtucket meant the East Ends had “practically won” the New England League title.[49] For Boyd, it meant he had won two championships in a single day with two different clubs even though he played in only one match.

One week later on May 14, Boyd provided two assists as the East Ends defeated New York Thistle 5-2 in the American Cup final at the Kearny Athletic Grounds in East Newark, giving the Scotsman his third championship in a week and his club their second consecutive American Cup title. Indeed, it was Boyd’s second American championship if the assertions of the Chicago Thistle manager are to be credited. One report observed, “Boyd put up a grand game in center,” adding, “He is well known in New York and Newark, and is looked upon as the best player in the country.” The report also noted Patrick Gallocher “kept out of the way” and did not appear for New York Thistle: “the vengeance of the East End managers has been postponed.”[50] Attendance for the final was disappointing, especially after the 6,000 who saw the East End-Conanicuts semifinal in Fall River, with reports ranging from “a few hundred spectators” to “close upon 1500.” Meanwhile, a Mayor’s Cup match in Fall River between the Olympics and Rovers the same day as the American Cup final in East Newark drew nearly 2,000 spectators. One Fall River report complained, “Newark is not a football town, and only two posters of the game were seen.”[51]

Much of this grumbling reflected discontent toward the AFA in Fall River and Pawtucket where American Cup matches regularly drew larger crowds than those played in the seat of the AFA’s power in Newark/northern New Jersey. Plainly stated, the leading New England clubs felt their oversized contributions to the AFA’s coffers were not equally matched by political power within the association. How does this relate to Boyd? The Fall River Daily Herald reported that after the AFA took its 15 percent cut of the final’s gate receipts, the East Ends’ 50/50 share came to only $23, which means the total gate for the final was only $54. Yet the club’s expenses to travel to the final were $150, leaving it $127 in the red.[52] How this affected the club’s ability to pay Boyd for playing in the championship game is not known.

What is known is that Boyd almost didn’t play in the championship match after being accused of assault. On the evening of May 8, the Sunday before the American Cup final, Boyd allegedly attacked one Thomas Lee, striking and throwing him to the ground and only ceasing the assault when Lee pulled out a revolver. While two members of the Olympics later testified that Lee attacked Boyd first, Lee’s attorney argued “the management of the Olympic club was strongly interested in securing Boyd’s release.” The Fall River Evening News also reported, “Evidence was introduced to show that Boyd had made overtures towards a settlement, but this was probably so that he would not be prevented from playing with the East Ends in the coming [American Cup]-tie with the Thistles.” On May 20, the Friday after the American Cup final, Boyd was found guilty and fined $12 plus expenses.[53] Less than a year later on April 7, 1893, Boyd, now back in England and playing for West Bromwich Albion, was arrested for assaulting Richard Darby, described by Bradley et al. as a timber merchant and “well-known [West Bromwich] Albion supporter.” Ten days later, a warrant was issued for Boyd’s arrest after he failed to answer a summons. Boyd then “disappears from the Midlands, presumably returning to Scotland, where he signs for Third Lanark in May.” On July 12, 1893, Darby died at his home, “having failed, it is rumoured, to have fully recovered from being kicked by Boyd.”[54]

Boyd leaves Fall River and the US

Boyd received his New England League championship medal on May 28, 1892, after the last league match of the season, scoring the equalizer and game winner in the 3-2 win over Pawtucket Free Wanderers.[55] Boyd continued to play with the Olympics in the Mayor’s Cup and also appeared in a benefit match composed of sides picked from the New England League. Mayor’s Cup play continued into July with the Olympics in a three-way tie for first place when the tournament was suspended until fall; aside from temperatures being considered too hot for playing soccer, the sporting public’s attention was now focused on baseball and cricket. On July 10 representatives of the clubs meeting to plan for the upcoming New England League season adopted a new rule directly related to the eligibility controversies surrounding Henry Boyd. Now, it was decided, “any player signing a New England league contract would have to play with that club in all other competitions.” Signing with one club for one competition and another club for a second competition was no longer allowed. Clubs fielding a player not signed with them would be fined $25 and would forfeit the game. An unsigned player appearing for a club would be fined $5 and suspended from playing in any match for one month.[56]

One day after the new rules were announced, reports said Boyd had signed with Fall River Rovers along with three other former Olympic players. According to one report, “Boyd received $25 to sign with the Rovers,” the equivalent of about $740 today.[57] Boyd’s signing with the Rovers came amongst a signing frenzy by Fall River’s leading clubs that some viewed with alarm and newspaper reports lamented the creeping effects of professionalism on the game. With signing bonuses “as high as $100 down and $15 per week” – about $2,986 and $448 respectively in today’s dollars, well above the average worker’s wage in Fall River — it was feared quality players would be concentrated in one or two teams who might go so far as to sign players not to play them every week but to prevent them from playing with competitors.[58] Whatever the ability of leading clubs like the East Ends and Rovers to fulfill the terms of the contracts they offered, competitive balance was viewed as threatened and it was asserted fans would lose interest in following teams that did not have the resources to secure top players and effectively contend for championships. One report observed, “the limits of the game in this country are altogether too narrow to admit of hiring players, adding, “There are too few good men who are worth a stipend to equip more than two elevens in this city.” Only if “a method of distributing players is adopted as prevails in the baseball leagues” could the dangers of professionalism be avoided.[59] Boyd’s “sympathies” were with the club that had convinced him to move from Chicago but the “financial condition of things” for the Olympics was not good and the club was in danger of losing its grounds.[60]

Whatever his sympathies, Boyd skipped town soon after signing with the Rovers. He was last seen on July 24 inquiring “what time the boats left for New York,” from where he presumably booked passage back to Britain.[61] According to Bradley et al., on August 8, two weeks and a day after he left Fall River, Boyd was in England to sign with Burnley, the team recommended to him by Patrick Gallocher.[62]

Conclusion

Henry “Harry” Boyd’s time in the United States presaged patterns that would become apparent during his later playing career in Britain. In both the US and in Britain, Boyd demonstrated both an ability to get clubs to pay for his travels and a willingness to abandon clubs when it suited him, reinventing himself as he attempted to rejuvenate his playing career with each move. In both the US and Britain, he also demonstrated a propensity for violence off the field that led to encounters with the law. He also showed himself to be a natural goal scorer despite sometimes being played at fullback.

More generally, Boyd is emblematic of trends then emerging in the US soccer scene. The abundant and grandiose praise used to describe Boyd’s quality as a player underscored the varying quality of play evident in the US and the continuing importance of foreign-born players in improving the standard of play. Boyd’s example also highlights an aspect of player movement that thus far has been little documented in which players from Britain played for a time in the US before returning home to continue their careers.

Long distance tours such as Chicago Thistles’ visit to Fall River demonstrated the willingness of leading clubs in one region to test themselves against leading clubs in other regions, both for prestige and for profit and also for identifying and acquiring new talent. Those governing bodies that did exist were limited by their regional jurisdiction or by being limited to a specific competition. As new competitions were launched governing bodies found themselves inherently reactive when confronted by players such as Boyd who were adept at exploiting an environment that saw clubs competing for limited resources of high-quality talent.

Such an environment was also marked by the ongoing tension between amateurism and the emerging professionalization of the game. This tension continued for decades. Only two years after Boyd departed the US the precarious position of professional soccer became more obviously apparent in the short-lived professional leagues the American Association of Professional Football and the American League of Professional Football.[63] Indeed, as we have seen, the strain created by professionalism could be apparent within a club between players receiving unequal payment for their services. Even in a city as enthusiastic for soccer as Fall River, the sustainability of professionalism was a real question, even without the looming effects of a national economic crisis like the Panic of 1893 complicating possibilities. Nevertheless, with signing bonuses, compensation for training, weekly stipends, a cut of gate receipts, and flexible employment opportunities from supportive businesses, it is apparent a respectable income was possible for high caliber players like Boyd, Patrick Gallocher, and Neil Munro who were willing to move between clubs in a given area or open to opportunities offered by clubs in other areas. Whether clubs could survive paying such incomes was often doubtful.

Henry “Harry” Boyd US appearances by club

| Club | Appearances | Goals |

| Chicago Thistle | 4 | 4 |

| Fall River Olympics | 10 | 7 |

| Fall River East End | 10 | 6 |

| New England League No. 2 Team | 1 | 0 |

| Total | 25 | 17 |

Henry “Harry” Boyd US appearances by competition

| Competition | Appearances | Goals |

| Chicago Thistle Tour | 4 | 4 |

| Bristol County Cup | 5 | 6 |

| Mayor’s Cup | 4 | 0 |

| New England League | 4 | 5 |

| American Cup | 3 | 2 |

| Exhibition Matches | 5 | 0 |

| Total | 25 | 17 |

Endnotes

[1] Robert Bradley, Douglas Gorman and Colin MacKenzie, “Henry Boyd – a talented but tainted footballer.” Scottish Sport History, https://www.scottishsporthistory.com/uploads/3/3/6/0/3360867/henry_boyd_-_a_talented_but_tainted_footballer_final.pdf

[2] Andy Kelly, “Henry Boyd, Arsenal’s top goal scorer on a goals per game ratio: an update,” The History of Arsenal, https://blog.woolwicharsenal.co.uk/archives/4588

[3] Bradley, “Henry Boyd,” 5.

[4] Bradley, “Henry Boyd,” 2-3.

[5] “UK and Ireland, Outward Passenger Lists, 1890-1960,” database online, Ancestry.com (https://www.ancestry.com/imageviewer/collections/2997/images/40610_B000043-00089?treeid=&personid=&hintid=&queryId=470ed141c27c0e9a0a6fabd4fea0bc72&usePUB=true&_phsrc=InW302&_phstart=successSource&usePUBJs=true&pId=35847424 : accessed July 18, 2021), Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2012. Entry for Henry Boyd; “Pennsylvania, Philadelphia Passenger Lists, 1883-1945,” database with images, FamilySearch (https://familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:33SQ-GP1W-9Y9N?cc=1921481&wc=M616-N66%3A214203101 : 6 June 2014), 015 – v. V-W, May 1, 1891-Dec 30, 1891 > image 113 of 822; citing NARA microfilm publication T840 (Washington, D.C.: National Archives and Records Administration, n.d.). Accessed July 20, 2021; “Hard Gales and Heavy Seas,” Philadelphia Inquirer, May 15, 1891, 7.

[6] Boyd, Henry. 1881 Scotland Census [database on-line]. Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2012.

[7] “Swifts Versus Thistles,” Chicago Tribune, May 16, 1891, 6; “Foot-Ball,” Inter Ocean, May 17, 1891, 2; “Thistles vs. Braidwoods Tomorrow,” Chicago Tribune, May 29, 1891, 6; “Thistles vs. Braidwoods Today,” Chicago Tribune, May 30, 1891, 6; “Football,” Inter Ocean, May 30, 1891, 3; “Thistles Versus Braidwoods,” Chicago Tribune, August 16, 1891, 7; “Did Not Make a Goal,” Chicago Tribune, August 17, 1891, 6.

[8] Modesto (M.J.) Donna, The Braidwood Story (Braidwood, Ill.: Braidwood History Bureau, 1957), 244-245.

[9] Jillian Boyd, Ancestry message to Kurt Rausch, June 2, 2021 and July 3, 2021.

[10] Robin F. Woods, “A Story of James ‘Jimmie’ Braidwood 1832-1879,” Mini Biographies of Scots and Scots Descendants, https://electricscotland.com/webclans/minibios/b/braidwood_james.htm

[11] “Public Member Trees,” database, Ancestry.com (http://www.ancestry.com : accessed 5 July 2021), “The Mackiney/Hutchison Story” family tree by Ernest Allen, profiles for William Boyd (1835-1898, d. Glasgow, Scotland) and Colin Boyd (1871-1944, d. Virden, Illinois, United States).

[12] “Foot Ball Game,” Streator Daily Free Press, January 2, 1891, 3.

[13] Gabe Logan, The Early Years of Chicago Soccer, 1887-1939 (Lanham, Md.: Lexington Books, 2019), 15, 27-30, 33.

[14] “Football Notes,” Chicago Tribune, September 7, 1891, 6.

[15] “Mud and Whitewash,” St. Louis Globe & Democrat,” February 24, 1890, 8.

[16] “Foot-Ball,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, March 8, 1891, 24; “They Think They were Ill Used,” Chicago Tribune, March 9, 1891, 2; “The Champion Thistles,” Inter Ocean, April 20, 1891, 2.

[17] “Chicago Beaten by Berlin After a Hard Game,” Toronto Daily Mail, May 26, 1891, 6; “American Football Players Defeated at Seaforth,” Toronto Daily Mail, May 29, 1891, 2.

[18] “The Kicking Sport,” Fall River Daily Globe, September 8, 1891, 8.

[19] Gabe Logan, The Early Years of Chicago Soccer, 1887-1939, 34.

[20] “Football Passes,” Fall River Evening News, August 18, 1890, 8; “Rovers Defeated,” Fall River Daily Globe, September 22, 1890, 8; “The Kicking Trip,” Fall River Daily Globe, January 22, 1892, 3.

[21] “Football at Lake Forrest,” Chicago Tribune, September 17, 1891, 6.

[22] “Football,” Fall River Evening News, September 17, 1891, 8.

[23] “American Association Heard From,” Fall River Evening News, January 20, 1892, 4; “Football Notes,” Fall River Daily Globe, September 18, 1891, 7; “Football Notes,” Fall River Daily Globe, September 17, 1891, 7; “Football Passes,” Fall River Evening News, September 18, 1891, 8.

[24] “Football,” Fall River Evening News, September 21, 1891, 8.

[25] “Splendid Game,” Fall River Daily Herald, September 25, 1891, 4; Fall River Daily Globe, September 28, 1891, 7.

[26] “East Ends and Thistles,” Fall River Evening News, October 5, 1891, 8.

[27] “Foot-Ball,” Inter Ocean, October 15, 1891, 6

[28] “Football Passes,” Fall River Evening News, December 10, 1891, 8.

[29] “Another Rumpus,” Fall River Evening News, February 23, 1892, 1.

[30] “Local Sporting Matters,” Fall River Daily Herald, December 11, 1891, “Minor Locals,” Fall River Evening News, December 21, 1891, 8; “A Variety of Gossip,” Fall River Daily Herald, December 25, 1891, 4; “A Variety of Gossip,” Fall River Daily Herald, December 21, 1891, 4.

[31] Bradley, “Henry Boyd,” 5. Historical currency conversions in this essay were made using the US and UK CPI Inflation Calculators at https://www.in2013dollars.com/.

[32] “Three to Three,” Fall River Daily Herald, December 25, 1891, 4

[33] “Rain and Mud,” Fall River Daily Herald, January 4, 1892, 4.

[34] “New Football League Organized,” Fall River Evening News, January 8, 1892, 8.

[35] “New Bedford has no Attractions for Good Football Players,” Fall River Daily Herald, Jan. 22, 1892, 1.

[36] Massachusetts Bureau of Statistics of Labor, Massachusetts Labor Bulletin. No. 5, January 1898, 13.

[37] “Football Passes,” Fall River Evening News, February 1, 1892, 1.

[38] “Very Near Disbandment,” Fall River Daily Herald, February 1, 1892, 4.

[39] “Football Passes,” 1; “Local Sporting Matters,” Fall River Daily Herald, Feb. 3, 1892, 4; “Boyd’s Eligibility,” Fall River Daily Herald, April 22, 1892, 4.

[40] “Local Sporting Matters,” Fall River Daily Herald, February 5, 1892, 1; “Local Sporting Matters,” Fall River Daily Herald, February 6, 1892, 1; “Football,” Fall River Evening News, February 8, 1892, 1; “Local Lines,” Fall River Daily Globe, February 8, 1892, 7.

[41] “Local Sporting Matters,” Fall River Daily Herald, February 11, 1892, 4. Fall River newspapers spelled his last name as “Gallagher” and “Gallocher.”

[42] “Five Goals to Two,” Fall River Daily Herald, April 11, 1892, 4. The report mixes up team names: “Gallagher had left the city and was playing the same day with the Chicago [sic New York] Thistles against New York [sic Brooklyn] Longfellows.”

[43] “A Variety of Gossip,” Fall River Daily Herald, May 2, 1892, 1.

[44] “Another Rumpus,” 1; “A Rough Game,” Fall River Daily Globe, February 23, 1892, 8; “Sporting Events,” Fall River Daily Herald, February 23, 1892, 4; “Bristol County Football Meeting,” Fall River Daily Globe, February 25, 1892, 7; “Olympic Foot Ball Club Censured,” Pawtucket Evening Times, February 25, 1892, 2; “Bristol County Association Meeting,” Fall River Daily Globe, April 123, 1892, 1; “Football Passes,” Fall River Evening News, April 14, 1892, 8.

[45] “One Big Game,” Fall River Daily Globe, March 28, 1892, 8.

[46] “The Mayor’s Cup,” Fall River Daily Herald, April 8, 1892, 4; “A Variety of Gossip,” Fall River Daily Herald, April 8, 1892, 4; “His Honor Kicked Off,” Fall Rive Daily Globe, April 8, 1892, 7-8.

[47] “Kicking Over a Kicker,” Fall River Daily Herald, April 20, 1892, 1; “Boyd’s Eligibility,” 4.

[48] “Football Games!” Fall River Daily Herald, May 2, 1892, 1.

[49] “Football,” Fall River Evening News, May 9, 1892, 8; “New England Standing,” Fall River Evening News, May 9, 1892, 8; “Olympics Get the Cup,” Fall River Evening News, May 9, 1892, 8.

[50] “Won it Again!” Fall River Daily Herald, May 16, 1892, 4.

[51] “Championship Glory,” Fall River Evening News, May 16, 1892, 1; “The Cup Goes to Fall River,” The Sun (New York), May 15, 1892, 5. “The Olympics Win,” Fall River Daily Herald, May 16, 1892, 4; “Won it Again!”, 4.

[52] “The Cost of the Cup,” Fall River Daily Herald, May 18, 1892, 4. If admission to the final cost 15 cents and the gate took in $54, only 360 people paid to see the final.

[53] “A Football Player in Court,” Fall River Evening News, May 20, 1892, 8.

[54] Bradley, “Henry Boyd,” 3.

[55] “Local Sporting Matters,” Fall River Daily Herald, May 28, 1892, 4; “Hard to Beat,” Fall River Evening News, May 31, 1892, 5.

[56] “Stringent Rules,” Fall River Daily Herald, July 11, 1892, 4.

[57] “Football Notes,” Fall River Daily Globe, July 12, 1892, 7; “Football Passes,” Fall River Evening News, July 12, 1892, 8. “Local Sporting Matters,” Fall River Daily Herald, July 13, 1892, 4.

[58] “Football Contracts,” Fall River Daily Globe, July 16, 1892, 7.

[59] “Professionalism,” Fall River Daily Herald, July 21, 1892, 1.

[60] “The Olympics,” Fall River Daily Herald, July 13, 1892, 4.

[61] “Local Sporting Matters,” July 27, 1892, 1. Boyd’s decision to return from the United States echoed a similar decision made by his brother John in Braidwood three months earlier. Coal production in Braidwood hit its peak in 1878 and the population of the town declined during the 1880s. Poor working conditions, low pay, and frequent (and often violent) strikes caused many to look for opportunities elsewhere. John, his wife Annie, and their three children John, Jessie, and James, departed in May from Philadelphia on the SS British Princess bound for Liverpool. See “UK and Ireland, Incoming Passenger Lists, 1878-1960,” database online, Ancestry.com (https://www.ancestry.com/imageviewer/collections/1518/images/30807_A000025-00366?treeid=&personid=&hintid=&queryId=606382f14b117ef66a39e7ee4f8ecf5e&usePUB=true&_phsrc=InW289&_phstart=successSource&usePUBJs=true&pId=5117560 : accessed July 18, 2021), Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2012. Entry for John Boyd.

[62] Bradley, “Henry Boyd,” 3.

[63] See Ed Farnsworth, “The AAPF and the ALPF: The beginnings of professional league soccer in the United States,” Society for American Soccer History, last modified July 24, 2018. https://www.ussoccerhistory.org/the-aapf-and-the-alpf-the-beginnings-of-professional-league-soccer-in-the-united-states/; Ed Farnsworth, “After the collapse: ALPF vs. ALPF in Baltimore and Fall River, 1894-96,” Society for American Soccer History, last modified April 27, 2020. https://www.ussoccerhistory.org/after-the-collapse-alpf-vs-alpf-in-baltimore-and-fall-river-1894-96/

Pingback: “The Noxious Scottish Weed”: Early North American soccer and the Laws of the Game – Society for American Soccer History

Fascinating! JC