A persistent challenge when researching the early history of soccer in North America is identifying what code was used when teams met to play “football.” Plenty of newspaper reports on football games can be found in the years following the codification of association football or soccer in December 1863, but the code by which these games were played is often obscure. Sometimes, a report might offer clues in the form of the details about who played on a team, the number of players, the positions where players line-up, or how points were scored. But even when such clues are available to rule out some form of rugby or Gaelic football, it is difficult to confidently conclude a “soccer-like” football game was in fact association football.

Because the rules of association football were first codified in England, it is easy to assume the Laws of the Game as promulgated by England’s Football Association would be the rules adopted by the first teams and leagues in North America. As we shall see, such an assumption would be at best only partially correct: the first soccer association in North America, Canada’s Dominion Football Association (1876) adopted the Laws of the Game published by Scotland’s Football Association, not England’s FA. When the Laws of the Game were harmonized by the FAs of England, Scotland, Ireland, and Wales differences still existed in the competition rules of each association. The first soccer association in the United States, the American Football Association (1884), followed the competition rules of the SFA.

The early dispersal of the Laws of the Game

On December 3, 1864, the New York Clipper published “Rules for Football” that appear to be an almost word-for-word recitation of the the preliminary version of the Laws of the Game agreed upon after England’s FA met in November 1863 but were substantially revised to forbid hacking and carrying the ball in the first official Laws of the Game adopted in December 1863. Also published in 1864, The American Boy’s Book of Sports and Games contains a description of football, but rules are described as “The Laws of Foot-ball, as Played at Rugby.”[1] The first sports book in the US containing Laws of the Game for soccer was Beadle’s Dime Book of Cricket and Foot-Ball, published in New York City in 1866; ten cents in 1866 was the equivalent of about $1.78 in today’s value. Forty of the book’s fifty pages are devoted to cricket. Unlike the thirteen Laws of the Game announced by the FA, the Beadle book contains fourteen Laws, breaking up Law 1 into two parts.[2] Some minor word changes aside, the Beadle book otherwise reproduces the 1863 Laws of the Game and does not include changes adopted by the FA in February 1866 for the second edition of the Laws. Five years passed before a new publication of the Laws of the Game appeared in the US. During that time, the FA adopted revisions to the Laws of the Game in 1866, 1867, 1869, 1870, and 1871.

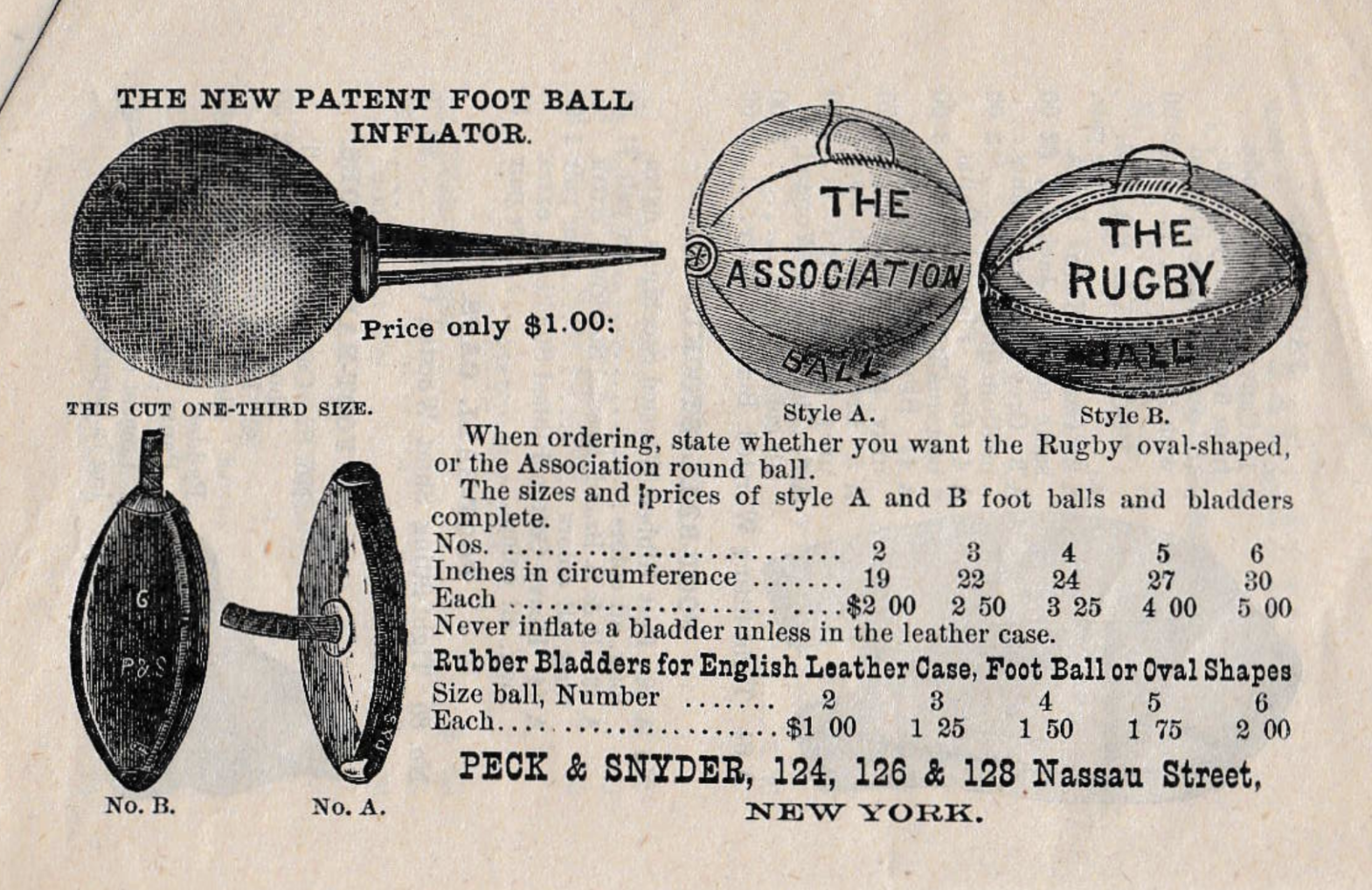

Issued to “supply an acknowledged want in Colleges and Schools throughout the United States,” Peck & Snyder published The Playing Rules of Football in 1871. While incorrectly claiming to be “the first book on Football, Styles of Playing, etc., ever published in this country,” The Playing Rules of Football was the most expansive to date. In recognizing the various codes by which football was played, the book reflected the unsettled supremacy of the various styles of football played in England less than a decade after the formation of the FA. Peck & Snyder’s interest in promoting football was financial: it was a sporting goods company in New York City and The Playing Rules of Football included advertisements for rugby and soccer balls, each available in six sizes. Like Beadle’s Dime Book of Cricket and Foot-Ball, The Playing Rules of Football was affordably priced, costing 15 cents, the equivalent today of about $3.50.

The Playing Rules of Football contains the Laws of the Game “of the principal clubs, public schools, and associations of England.” In addition to the FA’s Laws of the Game, also included are the rules for football as played by the Sheffield Football Association, Eaton College, Winchester College, the Rugby School, the Harrow School, and Cheltenham College.[3] Written by Charles W. Alcock, Honorary Secretary of the FA, The Playing Rules of Football contains the Laws of the Game as revised and adopted by the FA in February 1870 and does not include the revisions adopted in February 1871. The preface promises “Communications of interest on the subject of Football” would be “published in later editions.” Whether later editions did in fact appear is unclear.

It is difficult to know how widely available the Beadle and Peck & Snyder books were and their influence on spreading awareness of soccer. Certainly, The Playing Rules of Football had limited success at the time in fostering soccer’s adoption by US colleges and universities, which largely moved toward the adoption of rugby-style football. Awareness of soccer likely came from different sources. Those with access to British newspapers and sporting publications could find information about the sport. Accounts shared by newly arrived British immigrants and personal correspondence with friends and relatives in Britain were likely more influential sources of information about soccer’s development in Britain and how to play the game. But the impact of such publications and communications in the US was minimal in the 1870s. More than ten years would pass after the publication of The Playing Rules of Football before organized soccer began in the United States. Before that organized soccer in North America first appeared in Canada.

Scottish rules in Canada

The first soccer association to be formed in North America, and the first outside of the British Isles, was the Dominion of Canada Football Association, founded in Toronto in 1876. Writing in 1879, David K. Brown relates the DFA’s founding came about when “A number of Glasgow young men, who played the game there, found themselves congregated in the City of Toronto.” Brown, who came to Canada from Dalry, Scotland, explains,

A number of them being together one night it was resolved to attempt the introduction of association football. Rugby was then played with considerable vigour though not extensively, but the same feeling of dissatisfaction with it which led in England to the formation of the association prevailed here. This was supplemented here by the popular disfavour with which the Rugby game was regarded, on account of its roughness. These young men to whom I have referred were all members of the Carlton Cricket Club and they formed the Carlton Football Club, the first association club in Canada, and I believe on the continent.[4]

Neither the Beadle book nor the Peck & Snyder book appears to have made it as far as Toronto. The founders of the first soccer club in North America had only their memories to rely on for reference to the Laws of the Game, Brown recounts, and because of this “some absurd mistakes were made.” Such mistakes underscored the unreliability of memory as an authoritative source for the Laws of the Game: while this may have been sufficient for one-off or informal matches it was not acceptable for organized tournament or league play with a championship at stake.

Consequently, “A Scottish Annual was sent for, a meeting of clubs was summoned and the result was that the Dominion Football Association was formed and the rules of the Scottish Association adopted entirely.”[5] Brown also notes the DFA’s president, “His Excellency the Governor-General” — John Campbell, 9th Duke of Argyll – “is also Patron of the Scottish Football Association,” underscoring the DFA’s connections to Scotland[6] The first soccer team, and first soccer association, in North America was governed by the Laws of the Game as published by Scotland’s FA, not England’s FA.

Scotland’s FA was founded in March 1873. While its Laws of the Game were informed by the original Laws adopted in England, differences existed over the laws governing throw-ins, what a goalkeeper could do in handling the ball, and most significantly given its impact on tactical developments, the offside rule. These differences meant that when England and Scotland met in international play the Laws of the Game recognized by the home side governed the match. The rules were harmonized at a meeting in Manchester of representatives from the football associations of England, Scotland, Ireland, and Wales in December 1882, preceding the formation of the International Football Association Board four years later.[7]

So strong was the DFA’s Scottish connection that an 1878 US report described ambitious efforts by two DFA members who had returned to Scotland to organize a thirty-fixture tour of Canada and the US by two representative Scottish teams. The news was skeptically discussed in the Canadian press. As one report noted, the “‘Association game,’ which the Scottish teams which propose to visit us play, is almost entirely unknown in the United States, and by no means so universally played as the Rugby Union code in Canada.”[8] Despite such skepticism, hopes for a transatlantic visit persisted. A Scottish newspaper report in February 1880 described a match “between the Scottish team which is to visit Canada in a few months and the celebrated Darwen club in Lancashire.”[9] The successor to the DFA, the Western Football Association, organized in 1880, sent an all-association team to Britain for a 23-match tour of Ireland, Scotland and England in 1888 that overlapped with the founding season of England’s Football League. A combined Canadian American team followed for an even more grueling series of 58 matches in Scotland, Ireland, England, and Wales in 1891. But the long hoped for visit to North America by a Scottish side did not take place until 1921.

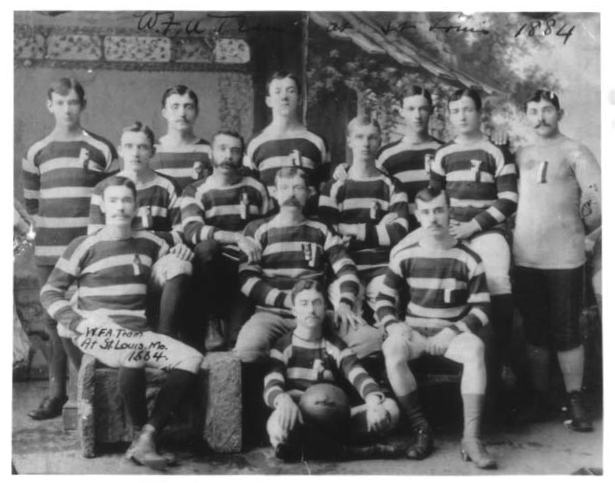

The WFA’s Scottish connections were evident before the first Canadian team visited Britain in 1888. When a WFA team traveled to St. Louis over the Christmas holiday in December 1884 for the first international games played in the North America, its opening match was against the St. Louis Thistle club. The Thistle club was formed in October 1883 “by a number of Scotch residents, who delight in the animated struggles of the football field.” The WFA team won easily, defeating the Thistles 9-0 on Christmas Day before defeating an all-St. Louis side consisting of players from Thistle and the city’s Hibernian club 5-3 three days later. David Forsyth, the Perthshire-born captain of the Canadian team and the driving force behind the WFA, related in one local report that soccer was referred to as “the noxious Scotch weed,” one “bound to grow wherever it gets a hold.”[10]

The SFA issued annuals each year communicating updates and revisions to the Laws of the Game and competition rules. The annuals also included reports on soccer activities in Scotland and elsewhere and these included reports from Canada from at least 1878.[11] Beginning in 1885, the SFA’s annual also included reports on the activities of the American Football Association in the United States.

Scottish rules in the American Football Association

When the Paterson Football Club faced Paterson Caledonian Thistle in New Jersey in October 1883, a dispute ensued over who had won the match. Writing in the Paterson Daily Guardian, Thomas A. Tuffnell, president of the Paterson FC, a club comprised exclusively of Englishmen, “offered to submit the matter to the Scottish Football Association” for judgement. Whether the matter was submitted to the SFA is unknown. Why the SFA was proposed as arbiter is also unknown. Perhaps this was simply because Caledonian Thistle was a Scottish-based team. Still, it is notable that in one of the early centers of the game in the United States the authority of the SFA in governing soccer matters was recognized and perhaps even favored over the authority of England’s FA.

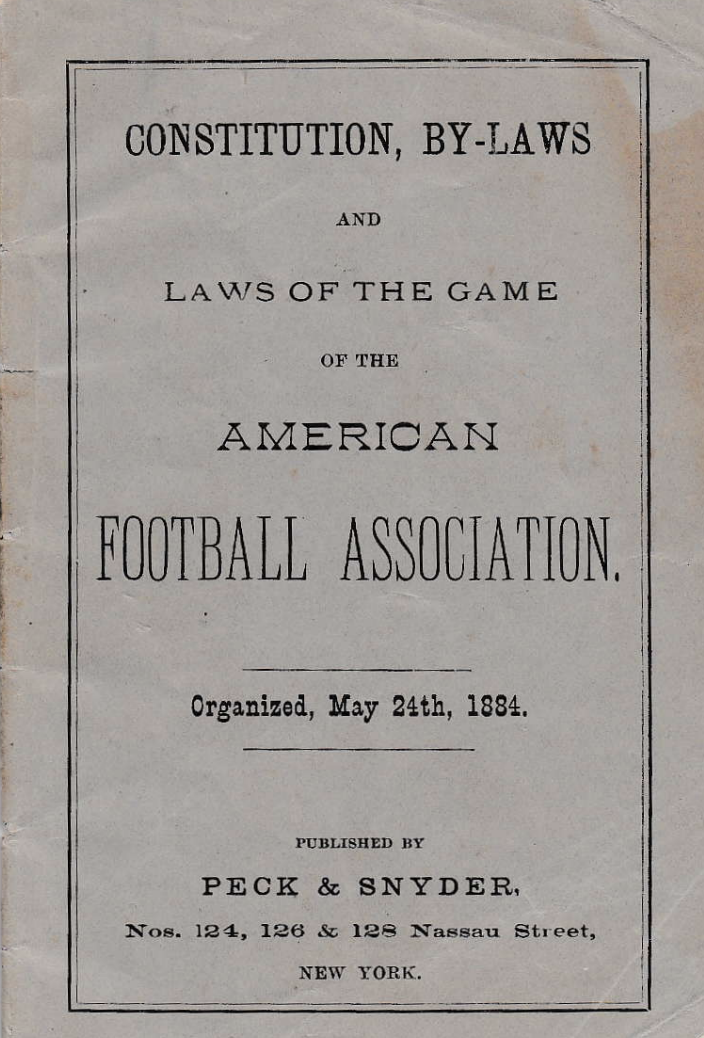

That a match dispute in New Jersey would be referred to a governing body located thousands of miles away underscored the absence of such a governing body in the US. This changed seven months after the Paterson-Caledonian Thistle dispute with the founding of the American Football Association. Formed at Caledonian Hall in New York City in May 1884, the AFA’s founding meeting included representatives from seven clubs, one each from New York City and Providence, Rhode Island, and five clubs from Newark, Passaic, and Paterson in New Jersey. Tuffnell was one of the representatives for the Paterson club.[12]

In October 1884, the Newark Sunday Call reported on the founding of the AFA, “The rules of the English association have been adopted, subject to alteration from time to time.”[13] Near contemporaneous evidence exists that the FA’s Laws of the Game were available in the United States at this time, even if what was available was not up to date. In December 1884, the Fall River Daily Herald published “The Laws of the Lancashire Association,” a word-for-ward recounting of the England FA’s 1881 Laws of the Game that omitted revisions made in 1882 and 1883.[14] However, a report in the SFA’s 1885-86 Annual written by AFA secretary P.J. O’Toole states “a revision of the Scottish rules” was the basis for the American association’s Laws of the Game.[15] An examination of the Constitution, By-Laws and Laws of the Game of the American Football Association, published in 1887 by Peck & Snyder, shows how in one important regard the AFA clearly followed the SFA, not the FA.

“Malignant evil”

If the Laws of the Game had by this point been harmonized among the football associations of England, Scotland, Ireland, and Wales, differences existed in each association’s competition rules. For the England and Scotland associations the fundamental difference revolved around the question of professional soccer. In 1885, England’s FA legalized professional soccer. How the FA governed professional players was an evolutionary process. Proposed new competition rules published in 1887 included eight sections of rules governing the use and eligibility of professional players.[16] Meanwhile, the SFA retained its ban of professional players until 1893.

Prior to legalization, the SFA’s penalties for using professional players were severe. The SFA’s Annual for 1884-85 said of the “malignant evil” that was professionalism, “All players found guilty of receiving remuneration for their services beyond their reasonable and legitimate expenses shall be disqualified from playing in any Club under jurisdiction of this Association for a period of two years.” Clubs were also “liable to expulsion from the Association” for using professional players.[17] The 1885-86 Annual reported 38 Scotchmen playing professionally in England had been banned from playing in Scotland.[18] In the 1886-87 SFA annual, the rule banning professional players included five additional subsections; the number of subsections related to professionalism grew to eleven in the 1889-90 SFA Annual. This included a ban on playing for money prizes.[19] The 1887 AFA rules were far simpler and allowed the growing association room for discretion. Rule 6, Section 2 stated plainly, “any players receiving payment for their services shall be disqualified for such a period as the Association may determine.”[20] This effectively banned clubs participating in the AFA’s American Cup tournament from using professional players. Thus, two years after England’s FA legalized them, the AFA continued to follow the SFA in banning professional players.

It is unclear whether the AFA followed the SFA’s evolving specificity about what constituted professionalism. The Constitution, By-Laws and Laws of the Game of the American Football Association published in 1887 is as of this writing the only extant edition to be discovered. Whether the AFA issued later editions before the association withered away at the close of the 1890s is thus unknown. After its revival in 1905, the association was closely aligned with England’s FA and professional clubs soon openly entered the American Cup tournament without fear of punishment.

AFA bans pros – sort of

If the AFA followed the SFA’s hard line against professionalism in the 1880s and 1890s, enforcement was weak. Among the list of fifteen affiliated clubs in the 1887-88 AFA Annual were the Rovers and East Ends clubs of Fall River and the Pawtucket Free Wanderers. Clubs from Fall River and Pawtucket formed the backbone of the AFA’s Eastern District and populated the list of American Cup winners between 1888 and 1894. Reports of professional players in Fall River can be found as early as 1885. AFA-affiliated clubs playing for cash prizes was common. Competition for top players in Fall River and Pawtucket was fierce and players were lured from Western District clubs in New Jersey and New York and as far away as Chicago. Newly arrived players from England and Scotland were quickly signed. Awarding signing bonuses and the sharing of gate receipts was standard practice when the New England League was inaugurated in 1891. By that time founding New England League clubs the Fall River Rovers had won the American Cup twice and Fall River East End and Fall River Olympics had each won the tournament once — and would do so again in 1892 and 1894, respectively. Pawtucket Free Wanderers would win the tournament in 1893. These clubs did so while openly breaking restrictions against professionalism as defined both generally by the AFA and specifically by the SFA.[21] The explanation for why the AFA was willing to turn a blind eye toward such infringements is likely simple. Professional teams were simply better than amateur sides, offering a higher level of play that drew bigger crowds. This meant bigger gate receipts and thus more money for the AFA, which took a fifteen percent cut of the gate from American Cup matches, the association’s principal means of funding beyond yearly membership fees for clubs, fees required to file a dispute, and any resulting fines. At the end of the 1880s and beginning of the 1890s Fall River-Pawtucket was arguably the most vibrant soccer scene in the US with matches there regularly attracting some of the largest attendance numbers yet to be recorded for soccer in the country. The AFA simply could not afford to alienate such a cash cow.

In 1894, a year after the SFA legalized professionalism, the AFA did act, banning players who signed with the short-lived American League of Professional Football and American Association of Professional Football. But the ban was not motivated by principles, even if those principles no longer applied in Scotland and England. Rather, the ban was a spiteful reaction to other football associations encroaching on the AFA’s sphere of influence. Ironically, before the ban was announced, the ALPF said its matches would be governed by “the American Association [AFA] rules of ’94,” which suggests the association did in fact publish annual updates to its rules.[22] We can only hope that copies of these updates will be discovered. Aside from providing insight into the length of any lag between the publication of revisions to the Laws of the Game by the SFA or FA and their adoption by the AFA — and what such a lag might say about the communication between the associations — whether and how the AFA followed the SFA’s stance against professionalism are questions begging for an answer.

Foundations

The relationship between the AFA and the SFA is underscored by the inclusion of reports on the activities of the American association beginning with the 1885-86 SFA Annual through the 1887-88 Annual, after which only activities in North America involving Canada are reported.[23] But none of these reports discuss efforts by the AFA to address professionalism in the United States, malignant or otherwise. The Constitution, By-Laws and Laws of the Game of the American Football Association of 1887 also included a short essay on the offside rule by the editor of the SFA Annual, John McDowall. Reports in US newspapers describe how the AFA continued to follow the SFA’s lead. A Fall River Daily Evening News report in November 1891 noted the AFA’s “intention to try the suspension rule of the Scottish Association on players who have been cautioned by the referee in cup games.”[24]

Why the AFA chose to follow the SFA rather than the FA is unknown. Unlike the origins of the DFA, there was no group of “Glasgow young men” to make the connection. The AFA’s membership was diverse. If the ONT roster, as one Lancashire-born correspondent in Newark wrote to the Manchester-based Athletic News, was “with one exception…all Lancashire lads” when the club won its first American Cup championship in 1885, its opponent, the New York club, was “composed entirely of Scotchmen.”[25] The names of AFA-affiliated clubs offer clues about ethnic connections: Kearny Rangers, Newark Caledonians, and New York Thistle point toward Scottish origins; Fall River Rovers, Tiffany Rovers, and Alma point toward English origins. But, as its name implies, the Domestic club, defeated by ONT in the first round of the 1884-85 tournament, was “entirely made up of native born who never saw a football, much less a game, before the present era.”[26]

One need not examine the genealogical records of players to see how such clues sometimes only go so far. While likely an example of exaggeration by an expatriate expressing pride in his new hometown club, the “all Lancashire lads” assertion about the ONT team is obviously belied by the fact that the club itself was sponsored by the Scottish-owned Clark Thread Company, whose headquarters was across the Atlantic in Paisley. Immigrants joining with the native-born to develop a new community is both a classic story of American history and a classic story of soccer history. The AFA, like the ONT club, was an organization of mixed heritage, reflecting the growing diversity of the metropolitan area from which it emerged. The association’s first president, James Grant, came from the Scottish-based New York club. Its first secretary came from the English-based Paterson club. Immigrants joining with the native-born to develop a new community is both a classic story of American history and a classic story of soccer history. Perhaps the SFA was simply more receptive to communications from emerging soccer frontiers than was the FA.

Soccer’s development in the opening decades of its history in North America was led by immigrants from England, Scotland, Ireland, and Wales, and their native-born American and Canadian descendants. In different locations and at different times, leading players, organizers and administrators, and the clubs, leagues, and associations for which they played and worked, might reflect specific national origins in what was once the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland. In later decades immigrants from other countries sustained and grew the game. All contributed to the foundation of soccer in Canada and the United States.

But the rule-making authority of the first soccer associations in North America was informed by the Football Association of Scotland rather than England’s FA. From such beginnings, the “noxious Scotch weed” would continue to grow.

Endnotes

[1] “Football Rules,” New York Clipper 12, no. 34 (December 3, 1864), 266; The American Boy’s Book of Sports and Games: A Practical Guide to Indoor and Outdoor Amusements (New York: Dick and Fitzgerald, 1864), 101-103.

[2] Henry Chadwick, ed., Beadle’s Dime Book of Cricket and Foot-Ball, Being a Complete Guide to Players, and Containing All the Rules and Laws of the Ground and Games (New York: Beadle and Adams, 1866), 41-45.

[3] Charles W. Alcock, The Book of Rules of the Game of Foot Ball, as adopted and played by the English Football Associations (New York: Peck & Snyder, 1871), 14, Preface.

[4] David K. Brown. Association Football: The Game, and How to Play It (Toronto: J. Ross Robertson, 1879), 4-5.

[5] Brown, Association Football, 5.

[6] Brown, Association Football, 7. For more on soccer’s beginnings in Canada see Colin Jose, Keeping Score: The Encyclopedia of Canadian Soccer (Vaughan, Ontario: The Soccer Hall of Fame and Museum, 1998), 2-6; Les Jones, Soccer: Canada’s National Sport (Toronto: Covershots Inc., 2013), 21-26.

[7] “National Football Conference in Manchester,” Glasgow Herald, Dec. 7, 1882, 5. For more details of some of the rules disputes, see Richard Robinson, History of the Queen’s Park Football Club, 1867 1917 (Glasgow: Hay Nisbet & Co, 1920), 54-56. Retrieved Mar. 25, 2022, from http://sfha.org.uk/HistoryoftheQueensParkFC.pdf. The PDF copy does not have the original page numbers so the pages referenced in this citation correspond to the PDF page numbers

[8] “Foot-Ball,” Montreal Daily Star, Nov. 28, 1878, 1.

[9] “Scottish Canadian Team v. Darwen (Lancashire),” North British Daily Mail, Feb. 9, 1880, 6.

[10] “Foot-Ball,” St. Louis Daily Globe-Democrat, Oct. 15, 1883, 10; “Sporting,” St. Louis Daily Globe-Democrat, Dec. 26, 1884, 10; “Sporting,” St. Louis Daily Globe-Democrat, Dec. 29, 1884, 10.

[11] “Association Football in Canada,” in Scottish Football Association Annual, 1878-79, ed. William Dick (Glasgow: W. Weatherston & Son, 1878), 30-31.

[12] Football,” Paterson Daily Guardian, May 26, 1884, 3.

[13] “Football in Newark,” Newark Sunday Call, Oct. 12, 1884, 1.

[14] “Football: Laws of the Lancashire Association,” Fall River Daily Herald, Dec. 17, 1884, 4. At first glance, it appears the Daily Herald lists only 14 Laws of the Game rather than the 15 in the 1881 FA Laws. But an error in the numbering of the list of Laws as printed by the Daily Herald following Law 13 sees the number 13 attributed twice. Law 14 in the 1881 FA Laws of the Game is misnumbered as 13 by the Daily Herald, resulting in Law 15 being misnumbered as Law 14.

[15] P.J. O’Toole, “The American Football Association,” in Scottish Football Association Annual, 1885-86, ed. John M’Dowall (Glasgow: H. Nisbet & Co., 1885), 112.

[16] “Proposed by the Committee. New Rules. The Football Association Rules” (1887). From the collection of Tom McCabe.

[17] John M’Dowall, ed., Scottish Football Association Annual, 1884-85 (Glasgow: H. Nisbet & Co., 1884), 24, 18.

[18] John M’Dowall, ed., Scottish Football Association Annual, 1885-86, 25.

[19] John M’Dowall, ed., Scottish Football Association Annual, 1886-87 (Glasgow: Hay Nisbet & Co., 1886), 21; John K. M’Dowall, ed., Scottish Football Association Annual, 1889-90 (Glasgow: Hay Nisbet & Co., 1889), 21-22.

[20] Constitution, By-Laws and Laws of the Game of the American Football Association (New York: Peck & Snyder, 1887), 13. From the collection of Kurt Rausch.

[21] For more on professionalism in Fall River and Pawtucket, see Ed Farnsworth, “The rise and fall: Fall River and Pawtucket soccer, 1883-1896,” Society for American Soccer History, last modified Feb. 1, 2022, https://www.ussoccerhistory.org/the-rise-and-fall-of-organized-soccer-in-fall-river-and-pawtucket-1883-1896/ and Ed Farnsworth and Kurt Rausch, “’Talented but Tainted’”: Henry ‘Harry’ Boyd in the US, 1891-92,” Society for American Soccer History, last modified July 27, 2021, https://www.ussoccerhistory.org/talented-but-tainted-henry-harry-boyd-in-the-us-1891-92/

[22] “Professional Football,” Philadelphia Inquirer, Jun. 20, 1894, 3. For more on the AAPF and ALPF, see Ed Farnsworth, “The AAPF and the ALPF: The beginnings of professional league soccer in the United States,” Society for American Soccer History, last modified July 24, 2018, https://www.ussoccerhistory.org/the-aapf-and-the-alpf-the-beginnings-of-professional-league-soccer-in-the-united-states/

[23] See for example O’Toole, “The American Football Association,” 112-113; Joseph Walden, “American Football Association,” in Scottish Football Association Annual, 1886-87, 111; Thomas B. Hood, “American Football Association,” in Scottish Football Association Annual, 1887-88, ed. John M’Dowall (Glasgow: Hay Nisbet & Co., 1887), 103-104; Kanata, “Over the Sea,” in Scottish Football Association Annual, 1890-91, ed. John M’Dowall (Glasgow: Hay Nisbet & Co., 1890), 87-89; Kanata, “Over the Sea,” in Scottish Football Association Annual, 1891-92, ed. John M’Dowall (Glasgow: Hay Nisbet & Co., 1891), 75-78; Kanata, “Over the Sea,” in Scottish Football Association Annual, 1892-93, ed. John M’Dowall (Glasgow: Hay Nisbet & Co., 1892), 74-76.

[24] John McDowall, “The Off-side Rule,” in Constitution, By-Laws and Laws of the Game of the American Football Association, 24; “Football Passes,” Fall River Daily Evening News, Nov. 6, 1891, 5.

[25] John West, “Football in America,” The Athletic News, May 26, 1885, 7.

[26] O’Toole, 113.

We M/s. Belfast Wears take the opportunity to introduce ourselves as a leading Manufacturer and exporter quality of Sports Wears, Soccer Wears, American Football Wears, Sublimation Wears, Compression Wears , Ice Hockey Wears , Basketball Wears , Hoodies , Sublimation Bras , Polo Shirts & All kind of Football Gloves etc.. to Worldwide for the last many years and have been achieved a good business reputation at all.

Ed Farnsworth, a top boy who provided me with invaluable assistance when I was researching my Granda Jock Curran’s pro playing career with the Philadelphia Soccer Football Club in the early 1920s. Jock was a Glaswegian who served in WWI. Thanks again, Ed! JC

Pingback: A soccer Christmas story, 1884 – Society for American Soccer History