Author’s note: In researching the AAPF and ALPF, I have received invaluable assistance and insight from Kurt Rausch, and also from Brian Bunk, as well as Grant Czubinski, Melvin Smith, Steve Holroyd, Roger Allaway, and Tom McCabe. My gratitude to each of them; any errors below are my own.

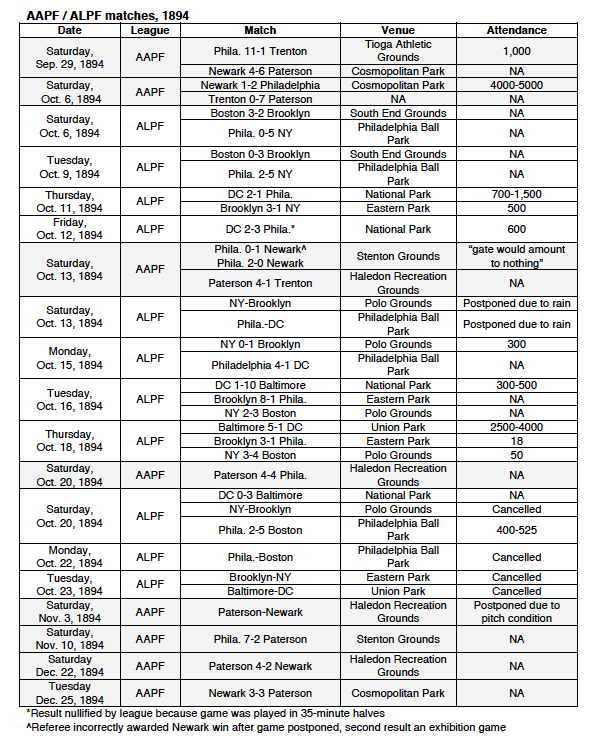

Given that much of the history of soccer in the United States is an ongoing exercise in rediscovery and recovery, it is remarkable that the existence of the country’s “first” professional league, the American League of Professional Football Clubs (ALPF), has been known for so long. Opening play on October 6, 1894, with Philadelphia suffering a 5-0 home loss to New York, and Boston defeating Brooklyn 3-2, the league announced it was ceasing operations only two weeks later on October 20. Despite its short history, the ALPF had something other than soccer to make it memorable: not only were six East Coast clubs of baseball’s National League behind the formation of the league, the recruitment of professional players from Britain resulted in the attention of immigration officials from the U.S. Department of the Treasury.

A brief account of the league’s brief existence is included in what might be called the first modern history of soccer in the United States, America’s Soccer Heritage: A History of the Game. Written by Sam Foulds and Paul Harris, America’s Soccer Heritage was published in 1979 at the height of the original North American Soccer League, the professional league whose spectacular rise helped to kindle the American public’s interest in soccer and whose demise in 1984 after years of precipitous spending and mismanagement marred the prospects for a top-flight U.S. professional league for a decade. U.S. Soccer vs the World (1983), which lists America’s Soccer Heritage in its bibliography, recounts the history of the league. Later, America’s Soccer Heritage was the starting point for discussion about the ALPF in two doctoral dissertation, “A Review of the Historical and Sociological Perspectives Involved in the Acceptance of Soccer as a Professional Sport in the United States” (1983) and “Historical Analysis of Four Major Attempts to Establish Professional Soccer in the United States of America Between 1894 and 1994” (1995).

While itself a slim volume of history, the account of the ALPF in America’s Soccer Heritage nonetheless stands out from other reviews of U.S. soccer history published at the time. Kyle Rote, Jr.’s Complete Book of Soccer (1978) contains some historical information, but no mention is made of the ALPF; the book is largely focused on explaining how soccer should be played. Neither The American Encyclopedia of Soccer (1980) nor The Great American Soccer Book (1980) mentions the ALPF. Indeed, the table of contents of The American Encyclopedia of Soccer even refers to the second American Soccer League as the “First Pro League,” omitting both the ALPF and the first ASL, that of U.S. soccer’s “golden era,” not to mention any of the various local and regional professional leagues that came in between. Inside Soccer: The Complete Soccer Book for Spectators, Players and Coaches (1980) acknowledges the first and second ASLs but the ALPF is absent; soccer’s “arrival” in the United States is clearly linked to that of the original NASL and Pele.

By the beginning of the 2000s, recognition of the short existence of the ALPF was assured, in large part because of work done by Steve Holroyd, who authored a page on the league at the American Soccer History Archives website titled “The First Professional Soccer League in the United States: The American League of Professional Football (1894)” (2000), which became a starting point for a new generation of U.S. soccer historians for whom the Internet was the first step in their research. Holroyd also later wrote the paper “The American League of Professional Football, 1894” for the journal Soccer History (2006). Now firmly established in the U.S. soccer history canon, the ALPF has an entry in The Encyclopedia of American Soccer History (2001), is mentioned in National Pastime: How Americans Play Baseball and the Rest of the World Plays Soccer (2005), The Ball is Round: A Global History of Football (2006), as well as Soccer in a Football World (2006), and more recently in American Soccer: History, Culture, Class (2015). Grant Czubinski’s three-part series (Part One, Part Two, Part Three) focusing on the Baltimore and Washington ALPF teams at his A Moment of Brilliance website from 2014 is a particularly thorough and insightful example of how regionally-based research has provided a deeper understanding of the league. “Football Hustlers,” published in the journal The Blizzard (2016), focuses on the Baltimore ALPF team’s importation of English professional players and provides much-needed detail on their fate after returning to England. Since the publication of America’s Soccer Heritage, much in the record has been corrected and more is probably known now about the league than at any time since its brief existence.

Missing in all of these accounts is the concurrent existence of another professional league, the American Association of Professional Football (AAPF), first described in “Philadelphia and the other first professional soccer league in the U.S.” (2015).[1] Since the publication of that article, further research has resulted in a more complete account of the AAPF.

“Irwin Springs Another Scheme”

Professionalism began to enter soccer in England in the 1870s and it did so through many guises: “Under-the-counter-payments, jobs in local firms, mock testimonials and a variety of other devices hidden on the club’s balance sheets…’broken-time’ payments for players who were forced to miss work to fulfill their Fixtures. Expenses and travel costs could also be covered for players.”[2] Hand in hand with professionalism came the recruitment of Scottish players by English clubs. In 1885, the Football Association, the governing body for soccer in England, legalized the use of professional players. In 1888, leading professional clubs organized the Football League. In Scotland, professionalism was adopted in 1891 and the Scottish League was formed in 1893.[3] Research by Melvin Smith identifies the beginnings of professionalism in U.S. soccer in Fall River and Pawtucket in 1889, with players moving between clubs for higher pay, but this did not lead to the creation of a professional league.[4]

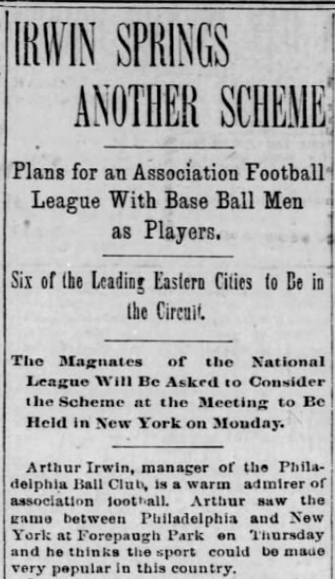

The origins of the first professional leagues in the United States are found in the series of annual inter-city games between the All-Philadelphia team of the Pennsylvania Football Union (PAFU), Philadelphia’s first organized league, and the Cosmopolitan team of New York City. The series began in 1891, two years after the founding of the PAFU in 1889.[5] When the two sides met on February 22, 1894, in what was supposed to be the deciding game of the series, each team had one win. Played in miserable conditions after an overnight snowstorm, the game ended in a 3-3 draw. But, more important than the result was the presence at the game of Arthur Irwin, the Canadian-born manager of the Philadelphia Phillies of baseball’s National League.

A “warm admirer of association football,” Irwin announced the day after the game a “scheme” to create a soccer league “composed of professional base ball men” that would play in the winter to “enable the ball players to keep in good condition”; Irwin’s concept of winter football for the purpose of maintaining the fitness of baseball players echoed proposals first floated withing the league in 1890. The new professional association football league was to be made up of six teams from the National League’s leading East Coast clubs: Baltimore, Boston, Brooklyn, New York, Philadelphia, and Washington D.C.[6] At the Broadway Central Hotel on June 19, the American League of Professional Football Clubs “was made a permanent organization…backed by the magnates of the six leading Eastern Clubs of the National Base Ball League.”[7]

While the publicized purpose of the league was to keep baseball players fit, it is apparent the real object was to make money during baseball’s long off-season by staging soccer games in otherwise empty stadiums. Irwin soon had a further incentive to make extra money: on August 6, the Philadelphia Base Ball Park, home ground of the Philadelphia Phillies, was almost entirely destroyed by a fire. Only the exterior outfield wall remained intact and for the rest of the National League season spectators were seated in temporary stands. A similar fire at Boston’s South End Grounds on May 15, 1894, had spread over twelve acres, leaving some 1,900 people homeless.[8]

With Irwin as the ALPF president, the league planned to play from October 1 through January 1 with teams playing four games against each opponent. This necessarily meant the league would not be restricted to playing only on weekends and that its fixture list would thus more resemble professional baseball’s schedule of weekday and weekend games; a report after the season was underway later described the “intention” to have three games a week.[9] “Home talent” was to be given preference for player signings with players reporting to their clubs by September 15 for “two weeks preliminary practice, so as to be in form for the opening of the championship season.” At the time of the June announcement, Philadelphia reportedly had already signed seven players and Washington eight, with the other clubs to “begin signing players in a few days.”[10] Teams were to wear white uniforms at home and “dark when traveling,” although at least one team personalized their uniform: Washington “selected red, white, and black” with “trousers” of “heavy white duck,” shirts featuring “wide black and white stripes,” and “skull caps, belts, and stockings of dark red.” The Washington team was also equipped with two sets of sweaters, “the lighter ones of solid red and the heavier ones of white and black horizontal stripes.”[11]

At the Fifth Avenue Hotel in New York on August 14, “the National Football League under the name of the American League of Professional Football Players” was formally organized. League secretary George Stackhouse, secretary of the New York Giants baseball team and a sports writer and editor at the New York Tribune, said after the meeting, “We have adopted a constitution which is not ready yet to be made public, but which is built on the same lines as that of the National Base Ball League, but it is not so bulky.”[12] Stackhouse said the ambitious league schedule would now run from October 1 through July 1, “inclusive,” with each team playing “five games in the different cities in the league.” The Sunderland club, champions of England’s Football League in 1891-92 and 1892-1893, was expected to visit the U.S. to “play a series of exhibition games in conjunction with the league.” A later report again said the inaugural season would end on January 1.[13] Player contracts would “extend for three months” beginning on September 15 with each of the six member clubs signing a partnership agreement “extending over three years…bound by a guarantee fund.”[14] Steve Holroyd writes ALPF owners “were anxious to impose the same monopolistic conditions” they enjoyed in baseball and adopted “a constitution identical to that of the National League.” With the “reserve clause” — which began as the “reserve rule” in 1879 and would remain in effect in baseball until the advent of free agency in 1976 — a “primary feature” of ALPF player contracts, players were potentially “little more than chattel to the owners.”[15]

Unsurprisingly, the ALPF was greeted with suspicion in soccer circles, where the backers of the new league were viewed as “carpetbaggers.”[16] At its annual meeting on September 15, the day ALPF player registration commenced, the American Football Association (AFA) unanimously approved a new rule banning any player “who has signed a contract and played with any National League club” from playing “in an American Association contest.”[17] Founded in 1884 and headquartered in Newark, New Jersey, the AFA was the organizer of the American Cup tournament, at the time the closest thing to a national championship tournament in the United States. The AFA’s geographic reach, while limited, nevertheless encompassed the soccer hotbeds in New England and northern New Jersey, and players from clubs who had participated in the American Cup tournament were naturally attractive to ALPF managers looking for talent. To the AFA, it was a case of the National League “encroaching on its own territory,” of “baseball magnates…tying to induce players to join” the ALPF.[18] As one report explained, the ALPF “offered salaries that would attract association players, who would count on running the three-month schedule with the league, and then be in readiness to participate in the association cup tie contests. This new rule, it is believed, will prevent all this.”[19] But the rule had little effect in preventing ALPF teams from signing players.

Mostly abandoning the “preference” for “home talent,” ALPF sides actively recruited players from other regions, particularly New England, home to Fall River and Pawtucket teams that had won the last seven American Cup championships. The Boston ALPF team unsurprisingly included nine players from nearby Fall River and Pawtucket; Brooklyn included “a number of the Fall River football team”; Philadelphia’s roster was also largely “from down East.” Recruitment wasn’t limited to New England, however: “most” of Washington D.C.’s roster was made up of players who “played professionally in Philadelphia and Trenton,” which again suggests that if professional leagues had yet to exist in the U.S., professional teams — or at least professional players — did. The “nucleus” of the New York team was made up of “members of the reserve team of the Preston North End club” then apparently living in New York City.[20] ALPF teams also weren’t above poaching players from their ALPF rivals. One player who had agreed to terms with the Washington D.C. team during the summer, “Brennan,” stopped in Philadelphia on his way to joining the team to visit several friends who were playing on the Philadelphia ALPF team. When he joined them at Philadelphia Baseball Park for a practice, Arthur Irwin liked what he saw “and notwithstanding that Washington has a claim on him, began to dicker with Brennan, and has, so far, succeeded in keeping him in Philadelphia.” It was the kind of player dispute a professional league was supposed to prevent and calls into question how effectively the ALPF had implemented the reserve clause baseball’s National League wielded so effectively to control the movement of players between teams. As the Washington Post reported, “It is not a very good example he is setting his fellow magnates.”[21]

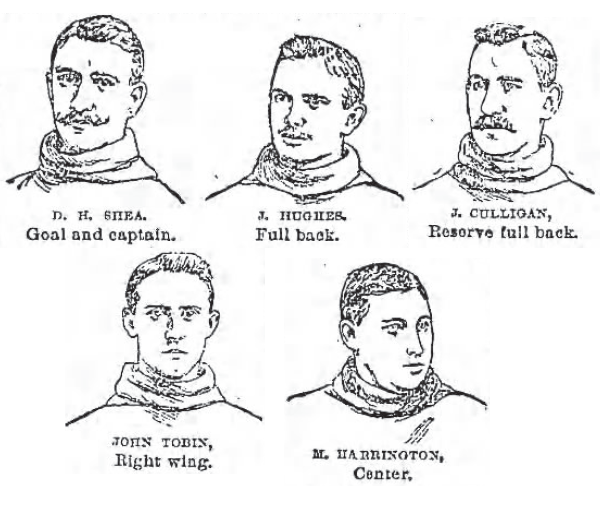

Reflecting participation in soccer generally in the U.S. at this time, many ALPF players were English and Scottish immigrants who had played in local clubs after arriving in the United States, although teams also actively “imported” players directly from England: Boston “sent abroad and secured” two players from Manchester while Baltimore’s recruitment of English professionals caused a scandal both in the U.S. and in England.[22] But native-born players were also present. They were widely represented on the Brooklyn team, itself made up of players from Fall River teams, particularly the Fall River Rovers. Only two players are clearly identified as being born in Britain — one English, one Scottish — with goalkeeper Dennis Shea, fullbacks James Hughes and James Culligan, and center forward Michael Harrington clearly identified as natives of Fall River, and right-winger John Tobin as a native of Boston; halfbacks Denis Fortin and John La Grosser are identified as French Canadian. Washington’s C. Shanahan was “a native of Trenton.” Future baseball Hall of Famer Sam Thompson and his Philadelphia Phillies teammate Charlie Reilly, the only Phillies baseball player to appear in most of the Philadelphia ALPF team’s games, were also native-born.[23]

“A rival league”

While most reports on the AFA ban emphasize its connection to the ALPF, one report describes, “Quite a lively discussion took place with respect to the professional leagues [emphasis added] recently organized,” adding, “it was decided that any player signing a contract and playing with any professional league team [emphasis added] shall be debarred from playing in any American cup tie games.”[24] The AFA was banning players associated not only with the ALPF but also from another newly founded professional league.

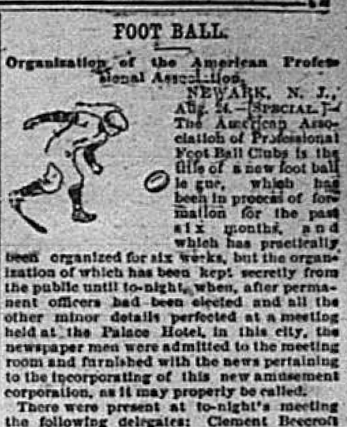

On August 25, ten days after reports on the formal organization of the ALPF, the Philadelphia newspaper The Public Ledger reported on a meeting at the Palace Hotel in Newark announcing another professional league, the American Association of Professional Football Clubs (AAPF).[25] According to the report, the AAPF “had been in process of formation for the past six months” and had been “practically organized for six weeks,” but the new league was “kept secretly from the public” until after the election of permanent officers “and all the other minor details perfected.” Announced to make up the league were teams from Philadelphia, New York, Brooklyn, Newark, Paterson, and Trenton, with Clement Beecroft, former president of the Pennsylvania Football Union and the manager of the All-Philadelphia team that faced the Cosmopolitans, elected as president of the new professional league. Recognizing the challenges weather conditions presented during the winter months, the league’s inaugural season would begin in September and run through January 1, with a spring season to run from the end of March through the beginning of June.

The AAPF’s spokesman at the meeting was Howard B. Hackett, a sportswriter for The New York World.[26] In a statement, he told reporters the league’s founding began “some time in March” when Beecroft wrote to a number of soccer administrators in “New York, Brooklyn, Trenton and several other cities” to ask their thoughts on forming a professional league. Several meetings followed in Philadelphia, New York, and Trenton. Hackett explained, “The American Association was practically organized as early as last June, and could have begun playing before a rival league, which I understand is now in process of formation, had held its first meeting.” That Hackett wouldn’t mention the ALPF by name says something of the antipathy toward the baseball-backed league.

If the ALPF’s August 14 announcement indicated much work was to be done before the league began play, Hackett repeatedly emphasized the AAPF was ready to play. The league schedule was arranged. The league was “an incorporated body” with a constitution and by-laws in place, and its player contracts would “stand the test of courts in New York, New Jersey and Pennsylvania.” Every club had eleven or more players under contract “so that each can put a team in the field on a day’s notice.” Each club had selected its colors and the Philadelphia team’s kits were already made.

Hackett positions the AAPF as a kind of anti-ALPF, with the spokesman questioning both the soccer knowledge and financial expectations of the baseball-backed league. Explaining the reasoning behind the AAPF’s schedule featuring games only on Saturdays and holidays, Hackett said, “football is not baseball, and those who are talking about playing four games per week evidently know nothing about the sport.” To play four games a week would require teams to have rosters of “23 to 33 players,” and this simply wasn’t economically feasible. Hackett also emphasized soccer was not yet popular enough to attract paying crowds on weekdays, particularly when the weather began to turn cold in November and December. More to the point, cold weather or not, soccer’s existing fan base largely consisted of immigrant factory and mill workers who were not in a position to leave work to watch a soccer game on a weekday. In 1894, a Monday through Friday 40-hour workweek with paid vacation and weekends off was but a dream for such industrial workers.

This reality informed Hackett’s recognition of the demographics of those who played — and by extension, supported — soccer. “First-class” players would not play on weekdays because soccer players “are nearly all skilled mechanics, who have positions in mills and factories paying them from $15 to $25 per week.” Why would these players give up their jobs for “a new venture that may not be a success in the end” when they could play on Saturday afternoons and holidays when “mills and factories are closed,” thus adding the money from playing soccer to their weekly wages, “which is more than any league could afford to pay them for ball playing exclusively.” Thus, AAPF players might be more precisely described as “semi-professionals” in that they worked other jobs during the week in addition to getting paid for playing soccer on Saturdays, compared to the “fully professional” players of the ALPF, for whom their soccer salary was their main source of income. Venturing into the realm of social judgment, Hackett said further, “Of course you can get players to sign for three months for $100 per month, but they are not the desirable ones to have. Good players are invariably good mechanics or tradesmen, who are steady in their habits, and therefore have steady employment…These are the players we want, not idlers who only work when they have to, and from whom good playing cannot be expected.”

Financial realities also informed the makeup of the league and its schedule. Hackett acknowledged the league could have included Boston and Fall River “but it would not have paid us the first year to do so.” By excluding the New England region, no team would have to journey more than a hundred miles for games and so the league’s travel expenses could be kept in check. Restricting the schedule to games on Saturdays and holidays not only meant soccer’s existing fan base could more easily see games, it also meant traveling teams would not have to remain overnight after a game, thus preventing any “heavy hotel expenses.” AAPF teams were also permitted to play “either professional or amateur elevens.”[27]

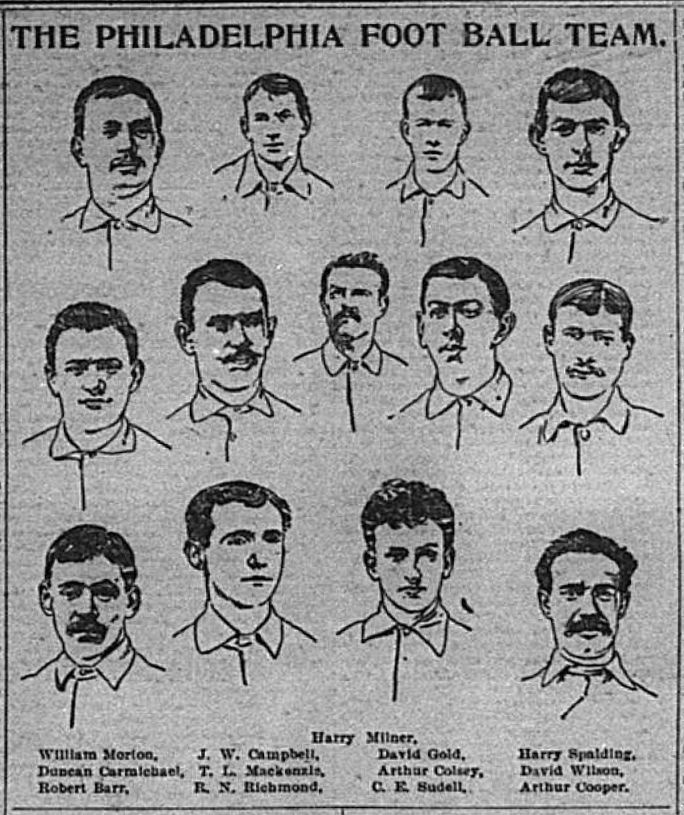

As for the teams themselves, the AAPF relied on local talent to create all-city sides, even though the players themselves were immigrants from Britain. In Philadelphia, the majority of the players on the 14-man roster were Scottish-born, the rest from England.[28]

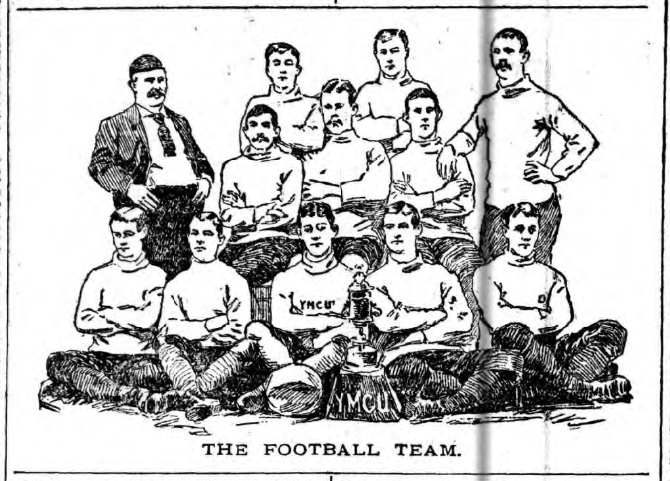

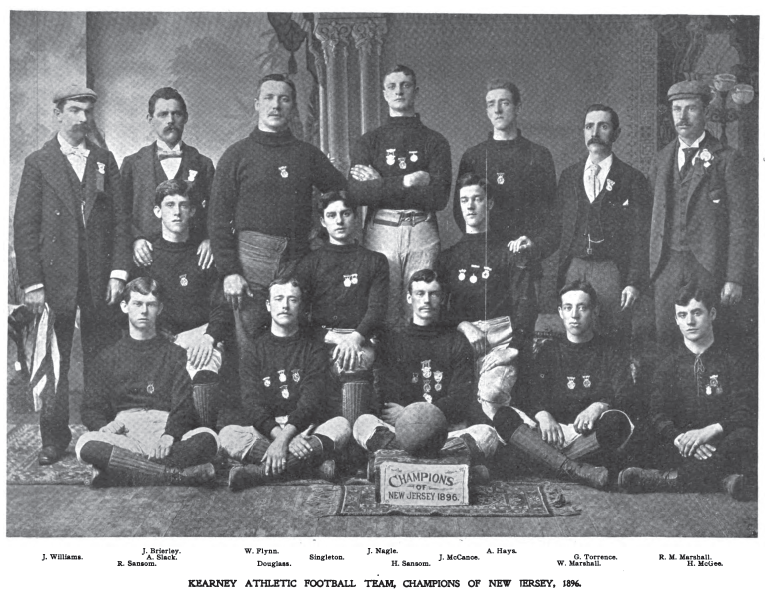

Most of Philadelphia’s players were from the PAFU championship-side the Athletics and had appeared on the All-Philadelphia team that had faced the Cosmopolitans. The “pick” of the Cosmopolitans, along with top talent from other New York clubs, was to fill the ranks of the New York team. In Paterson and Trenton, “the best players of several local teams” were selected to make “one powerful aggregation” for each city, while Brooklyn had assembled “a formidable aggregation.”[29] The Newark team was the Union Athletic Club of Kearny, also known as the Kearney Unions, a team that began as an exemplar of “muscular Christianity” as the Young Men’s Christian Union (YMCU) team of the Knox Presbyterian Church in Kearny and was a former champion of New Jersey.[30]

AAPF begins play before ALPF

In a preview of the first game of the AAPF season between the Philadelphia and Trenton teams, The Public Leger was clear which league, the American League of Professional Football or the American Association of Professional Football, was the first professional league in the United States: “The American Association was organized first and will be first in the field to seek popular favor.” To drum up interest in the game, 600 printed invitations were sent to ”city, State, Federal officials, prominent business men, well known society leaders and leading club men,” with a section of the grandstand at the Tioga Athletic Grounds reserved for invited guests. [31]

The Philadelphia AAPF team had been training since September 1.[32] On September 22, the team played an exhibition game against the Athletics, the former club of many of its players and reigning PAFU champions. On Saturday, September 29, 1894, the AAPF opened its season, with the Philadelphia AAPF team, managed by Clement Beecroft, hosting the Trenton AAPF team, while the Kearney Unions hosted Paterson in Newark. It was a day of goals. In “the first professional game of association football played in this city,” Philadelphia, wearing “blue pants and stockings and white shirts” easily defeated Trenton, wearing “white,” in front of “around 1,000 people,” 11-1. One report blamed “the unpropitious weather” and an international cricket match between the Gentlemen of Philadelphia and a visiting English team for the “poor attendance” — “near 10,000” attended the cricket match.[33] In Newark, Paterson, referred to as the Paterson League team in local papers, secured an “unexpected” 6-4 road win.[34]

New York-based AAPF sides did not join in play that day to open the season. Despite the league announcement little more than a month earlier confirming a six-club circuit, reports now said an “effort” was being made to “induce teams from New York and Brooklyn,” and that it was “expected” they would “shortly be embraced in this league.”[35] A league standings published on October 13 included “Cosmopolitans, of New York” — albeit with no results recorded — and reports on the Cosmopolitans’ annual meeting held the same day say games against “Philadelphia, Trenton, Paterson, Newark” — the home of AAPF teams — “will also be played.”[36] Perhaps it was a proposed visit to Canada that proved too much of a diversion, or the fact that the Cosmopolitan’s first practice game didn’t occur until October 27, or simply that the comparative embrace by New York newspapers of local ALPF clubs dampened enthusiasm, but a league standings published on November 1 makes no mention of the Cosmopolitans, and no New York or Brooklyn side ever entered into AAPF play.[37] Philadelphia was therefor the only city to be home to both an AAPF and ALPF team.

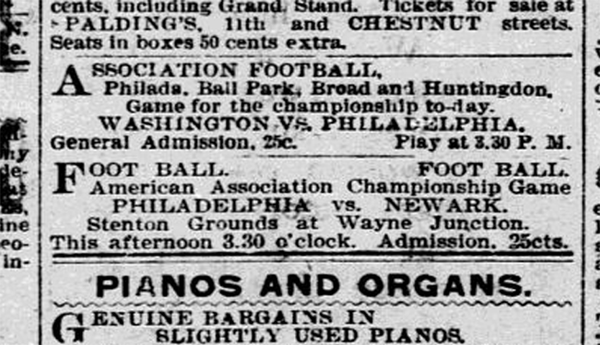

The same day the Philadelphia AAPF side played its first league game, the Philadelphia ALPF side played its first practice game, defeating the Athletics, 5-1. Two days later, the ALPF professionals defeated “a picked eleven,” 3-0, before defeating Philadelphia Wanderers, 3-1, the next day.[38] On October 6, 1894, one week after the start of the AAPF season, the ALPF opened league play, with Philadelphia hosting New York, and Boston hosting Brooklyn. With only three days of rest after playing three games in four days, the Philadelphia ALPF side was crushed in its home opener, losing 5-0 at Philadelphia Baseball Park in front of “about 500 people.” The game in Boston at the South End Grounds was more competitive — that the “majority’ of the players on both teams were from Fall River “caused intense rivalry” — and the home side won, 3-2.[39] Meanwhile, at Cosmopolitan Park in Newark, “between 4000 and 5000 persons” saw the Philadelphia AAPF side defeat the Newark-Kearney Unions, 2-1, in a “desperately fought” game.[40] In Trenton, the Paterson team, wearing “black and white with blue kickers,” defeated the home team, 7-0.[41]

The ALPF schedule continued with five weekday games, including two home openers. At home on Thursday, October 11, Washington D.C. won their season opener, 2-1, over Philadelphia, in front of what reports said were between 700 and 1,500 spectators. It was a good result, especially considering the Washington team was still being assembled as late as October 9.[42] The same day, Brooklyn defeated New York 3-1 in their home opener at Eastern Park in front of 500 spectators. [43] These were underwhelming numbers for home openers, and the attendance figures only got worse. The day after its home opener, attendance at National Park was down to 600 spectators when Philadelphia defeated Washington, 3-2, for their first win of the season, although “league officials” later nullified the result because the teams had played 30-minute halves rather than 45-minute halves as stipulated in the league rules.[44] After weather caused New York’s home opener to be postponed, only 300 spectators were in the stands at the Polo Grounds on Monday, October 15, when Brooklyn defeated the home team, 1-0.[45] Attendance for Baltimore’s home opener against Washington on October 18 — ten days after the ALPF began play — was variously reported at between 2,500 and 4,000 (Foulds and Harris incorrectly quote The Baltimore Sun as reporting attendance of “8,000” — they apparently referenced a poor microfilm copy — and that incorrect number has been repeated in later accounts of the league), but when Brooklyn hosted Philadelphia the same day and defeated them, 3-1, only 18 paying spectators were reported (this despite it being “Ladies day”), and only 50 were on hand at the Polo Grounds to see New York fall 3-4 to Boston.[46] Reported attendance in other ALPF games was never higher than 525.

In Philadelphia on Saturday, October 13, the city’s ALPF and AAPF teams were both scheduled to play. It was a prime opportunity to judge the relative popularity of each team with their hometown fans, but rain caused the postponement of the ALPF game against Washington D.C. There was real anticipation for the meeting between the Philadelphia and Newark AAPF sides after Philadelphia’s road win the week before, with one report saying, “the best of feeling does not exist between the two teams.”[47] However, the bad weather also caused Clement Beecroft to cancel that game. His reasoning came down to simple economics: “Professional foot ball, like professional base ball, is not played for glory, and when the weather is too bad for people to come out club managers would be foolish to send their teams on the field to play to ‘empty benches.’ To carry on a professional league there must be a gate to pay players’ salaries and other expenses, and club owners want to do this out of the receipts instead of out of their pockets.”[48]

Beecroft’s decision may have made sound economic sense but Newark-Kearney Unions had already traveled to Philadelphia for the game. Among those on the team were Alfred Cutler and Hugh McGhee, two Kearney Union players who had signed with the New York ALPF side and then bolted to rejoin the Unions before New York’s first game.[49] Rather than accept the postponement, the New Jersey side lined up on the field, kicked a goal into Philadelphia’s empty net, and claimed victory “by default.” The claim was “granted” by the referee, “who evidently has not yet read the constitution and by-laws of the Association.” According to AAPF rules, the home team was the “sole judge of the fitness of the playing field and conditions of the weather,” so the referee had no authority to allow a game, much less award a victory; said one report, “the referee’s decision will not go.” Without Beecroft’s consent, the Philadelphia team, perhaps smarting from the referee’s decision, then took to the field and defeated the visitors, 2-0, in an “exhibition game.”[50]

The Philadelphia-Newark game proved controversial for another reason when the Philadelphia newspaper The Times reported Beecroft’s players had given him “quite a talk” over unpaid wages before winning the exhibition game.[51] The report was vigorously denied in another Philadelphia newspaper, The Public Ledger, which reported the officers of the Philadelphia AAPF team were “indignant” over The Times article and that every player had in fact been paid.[52] The Times printed a retraction acknowledging that the president of the Philadelphia AAPF team, Horace Fogel, had provided documentation showing the players had been paid “right up to date…in strict accordance with their contracts.”[53] Fogel also happened to be a sports editor of The Public Ledger.

Despite “very unfavorable auspices,” the bad weather on October 13 did not prevent Paterson’s home opener at the Haledon Recreation Grounds, where they defeated Trenton, 4-1.[54] After three losses in a row, during which they allowed 22 goals while scoring only two, Trenton appears to have thrown in the towel following the defeat in Paterson and dropped out of league play, a not uncommon occurrence during the early days of league soccer in the United States.

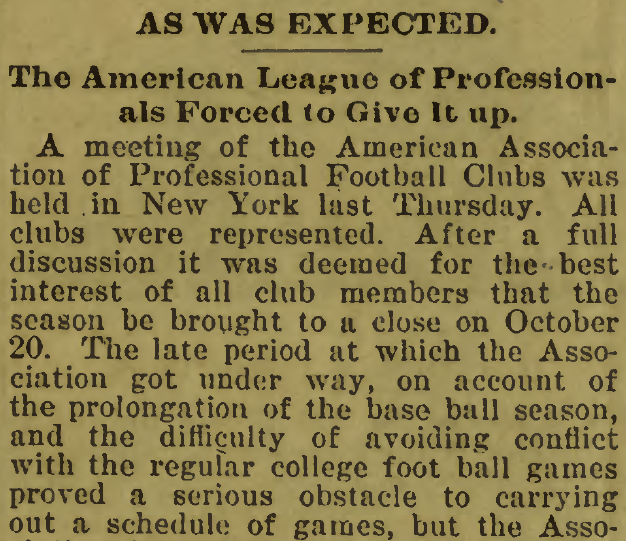

On Thursday, October 18, ALPF club representatives met in New York City. After “a full discussion of the situation,” the representatives decided it was in “the best interest of all club members that the season be brought to a close at once.”[55] The urgency of the decision was not met in action: while the ALPF decided on October 18 to shut down the season “at once,” a statement was not released to the press until October 20 and did not appear in newspapers until October 21. Thus, while the scheduled game between New York and Brooklyn was canceled, matches in Philadelphia and Washington DC were played, with Washington losing, 3-0, to Baltimore, and Philadelphia losing, 5-2, to Boston.[56] Strangely, in the league’s statement on closing the season, the name of the league is not stated as the American League of Professional Football but as “the American Association of Professional Foot Ball,” the name of its rival.[57]

The same day the ALPF decision was released to the press, Paterson hosted Philadelphia in AAPF play. One Paterson paper previewed the game by describing Philadelphia as “without a doubt the strongest team in America,” and Paterson warmed up for the game with a match against the team from the White Star Line steamship R.M.S. Majestic on October 17, defeating them, 6-3.[58] When Paterson and Philadelphia met, a “battle royale” followed that ended in a 4-4 draw.[59] With Trenton apparently out of the league, the Newark team, the Kearney Unions, played local amateur side Centreville, handing them a massive 15-0 defeat. Centreville soon after “made a complaint of professionalism” against the Kearney Unions to the AFA but after discussion, the complaint was dismissed.[60] Why the complaint was dismissed was not reported; perhaps the AFA reasoned if you play a team from a professional league and lose you can’t then complain that the team was professional. No AAPF games were scheduled for October 27 so Philadelphia played local amateur championship side the Athletics, winning 7-0.[61] Paterson was to host the Kearney Unions on November 3 but the game was canceled after bad weather resulted in poor pitch conditions.[62]

A tantalizing match in Philadelphia was also scheduled for November 3 between the city’s AAPF and ALPF sides. Weeks before, Clement Beecroft had challenged Arthur Irwin to a match to decide the professional championship of Philadelphia. On November 1, Philadelphia newspapers reported that, after “a great deal of dickering and badgering,” the rival managers had reached an agreement to play: “Manager Irwin has made a substantial wager that he has the best team, which Manager Beecroft accepted, and the game will no doubt be for blood as well as coin.”[63] But after more than an inch of rain fell on the city the morning of the game, the game was called off and the teams never met.[64] When the ALPF announced it was ceasing operations, it said that players under contract would be paid through November 1.[65] If Irwin could appeal to local pride to keep his professional side together two extra days for one last game, it seems unlikely that he would have been too interested in paying the team to keep it together after that. After all, given the team’s record in ALPF play — one win and seven losses with only seven goals scored and 23 conceded — the likelihood of Irwin winning his wager with Beecroft was clearly very slim. Later, Beecroft also challenged the Baltimore ALPF side to a match “to decide the championship of America,” but the Baltimore team disbanded five days after the challenge was reported, its notion of being the best soccer team in the country — inflated after sweeping the Philadelphia ALPF team in three games at home after the collapse of the league at the end of October — checked by a less than successful series of games in the beginning of November in Fall River the Brooklyn team aimed at settling the question of which was the best ALPF side.[66]

On November 10, 1894, the Philadelphia AAPF team hosted Paterson in a league game. Both teams were undefeated, “the two strongest teams in the race,” and Philadelphia newspapers promoted the game as one that was likely to decide the AAPF championship.[67] Despite the meaningfulness of the game, one aspect of its presentation spoke to soccer’s position in the wider sports landscape. The Philadelphia AAPF team had “arranged to receive special telegraphic bulletins” from the University of Pennsylvania-Princeton American football game being played in Trenton at the same time, “which will be announced to the spectators.”[68] Paterson, managed by William Turner, opened the scoring in the first five minutes of play, with Philadelphia equalizing soon after before the visitors scored again to take a 2-1 lead into halftime. With the resumption of play, it was all Philadelphia, who scored six unanswered goals to win, 7-2.[69] It was the last meeting between the Philadelphia AAPF team and other AAPF sides.

Philadelphia faced local amateur side Crescents on November 17.[70] On November 20, it was announced that Beecroft had accepted a challenge to play “the Princeton University eleven,” a team other contemporary reports incorrectly described as “the first association football organization in an American college.”[71] That the team was even from Princeton University is in doubt: The Daily Princetonian makes no mention of the game and an article a year later in the Alumni Princetonian says the “Princeton” team actually came from Princeton Theological Seminary, a separate institution.[72] Whatever the case, the Philadelphia AAPF team were easy 7-1 winners.[73]

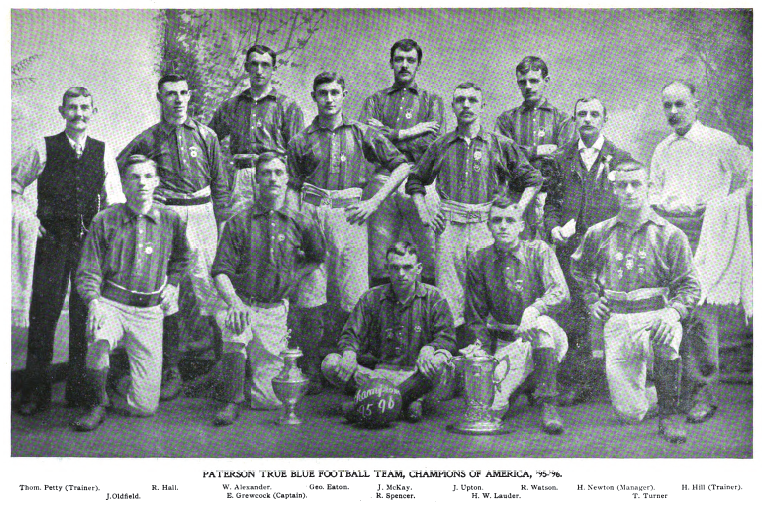

Paterson hosted two non-league games in November, first defeating the New York Cosmopolitans, 3-2, at home on November 24. On November 29, Thanksgiving Day, Paterson hosted the Paterson Thistles. According to one report, the Paterson Thistles were ineligible to enter the local amateur league, the Passaic County League, because “some of their best players are illegal, having played in the professional league.” Another report noted the Thistles “have sustained a severe loss owing to professional football springing up in America,” which may refer to the team having lost members to AAPF and ALPF sides, or to the team’s ineligibility to join the Passaic league.[74] Whatever the case, “considerable money” was wagered on the result of the match, with one Thistle club member reportedly willing to bet $500 that his team would best the local AAPF side. Thistle won the match, 4-3.[75] Meanwhile, the Newark AAPF team, the Kearney Unions, also arranged nonleague games, playing Newark Caledonians on November 10, and Paterson True Blues on Thanksgiving Day.[76]

On December 22, the Paterson League team and the Kearney Unions met in Paterson for the game that had been postponed in November. One Paterson paper, The Morning Call, said of the “great importance” of the game, “If the Patersons are successful in today’s engagement it will place their percentage on level with Philadelphia,” although it is unclear how the paper calculated this.[77] Paterson won the game, curiously described as “one of the most friendly games played in this city,” 4-2. On Christmas Day in Newark, the two teams met again and played to a 3-3 draw.[78] It was the last game between AAPF sides.

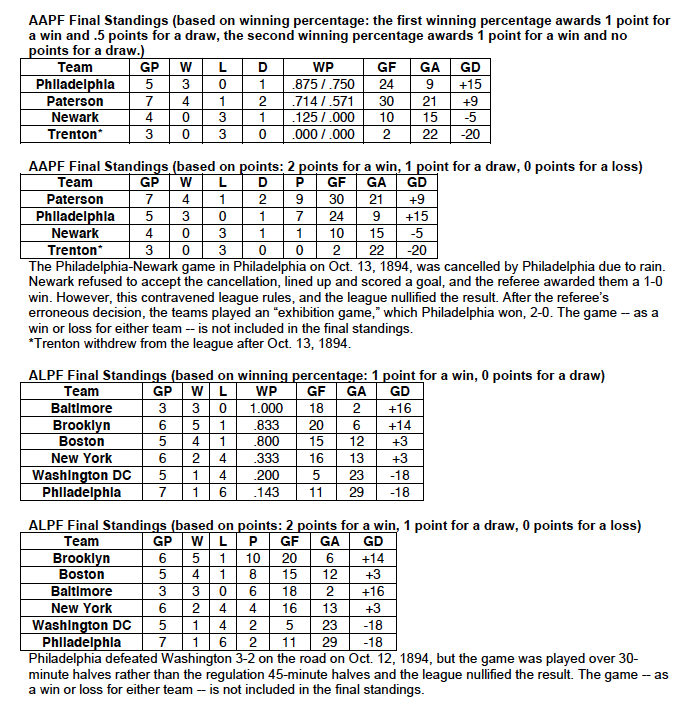

So, who was the AAPF champion? A report in the Public Ledger before the Philadelphia-Paterson game on November 10 said the teams were “tied for first place” before the game — which suggests the referee-awarded home loss to Newark was overturned by the league and the “exhibition” game was counted as a win to give both teams a record of three wins and one draw — and that Philadelphia “took the lead in the championship race” after defeating the Paterson League team.[79] Beecroft’s challenge to the Baltimore ALPF team to play for the professional championship of the United States indicates Philadelphia thought they were AAPF champions. But a preview of a game between the Paterson League team and Paterson True Blues that was played on May 4, 1895, for the championship of New Jersey says the Paterson League team “finished at the top of the inter-city League championship.”[80] The final standings are complicated by the fact that none of the teams that finished the season played the same number of games. Philadelphia only played Trenton once before they dropped out of the league while Paterson played them twice. When the league overturned the referee’s decision to award Newark a win in Philadelphia on October 13 because it contravened league rules, did the league record the game as no result or did it award Philadelphia a win for the “exhibition” game victory? Unfortunately, no reports provide a definitive conclusion and the two teams never met again to settle the question. Further questions remain. The first of the two Paterson-Kearney Unions games in December was clearly identified as the rescheduled game between the two teams that was supposed to be played on November 3 before being postponed. Was the second game, played on Christmas Day, a league game or an exhibition game?

So, who was the AAPF champion? A report in the Public Ledger before the Philadelphia-Paterson game on November 10 said the teams were “tied for first place” before the game — which suggests the referee-awarded home loss to Newark was overturned by the league and the “exhibition” game was counted as a win to give both teams a record of three wins and one draw — and that Philadelphia “took the lead in the championship race” after defeating the Paterson League team.[79] Beecroft’s challenge to the Baltimore ALPF team to play for the professional championship of the United States indicates Philadelphia thought they were AAPF champions. But a preview of a game between the Paterson League team and Paterson True Blues that was played on May 4, 1895, for the championship of New Jersey says the Paterson League team “finished at the top of the inter-city League championship.”[80] The final standings are complicated by the fact that none of the teams that finished the season played the same number of games. Philadelphia only played Trenton once before they dropped out of the league while Paterson played them twice. When the league overturned the referee’s decision to award Newark a win in Philadelphia on October 13 because it contravened league rules, did the league record the game as no result or did it award Philadelphia a win for the “exhibition” game victory? Unfortunately, no reports provide a definitive conclusion and the two teams never met again to settle the question. Further questions remain. The first of the two Paterson-Kearney Unions games in December was clearly identified as the rescheduled game between the two teams that was supposed to be played on November 3 before being postponed. Was the second game, played on Christmas Day, a league game or an exhibition game?

If it was a league game, Paterson played two more games than Philadelphia but suffered one loss — to Philadelphia — while Philadelphia was undefeated (assuming the October 13 game is recorded as no result). In straight points, Paterson bests Philadelphia but that is because they played the Kearney Unions three times, while Philadelphia only played them once (again, assuming the October 13 game is recorded as no result). Philadelphia bests Paterson on head-to-head record, goals scored, goals allowed, and goal difference. One method to determine a champion when teams do not play the same number of games is to calculate the winning percentage of each team, which was the basis of Baltimore’s claim to be ALPF champions after playing only three games (all against Washington, the next-to-worst team in the league after Philadelphia) before the league’s demise. [81] That this method was used is suggested by the reference in the Morning Call report to the Paterson League team’s “percentage,” and no reports have been found that confirm the AAPF — or the ALPF — awarded two points for a win and one point for a draw for league standings. Looking at nine different final AAPF record scenarios using two different methods to calculate win percentages produces 18 results, with Philadelphia the winner in 15 of the calculations. (Click here to see winning percentage scenarios.)

“As Was Expected”

Writing in Spalding’s Association Foot Ball Guide in 1905 eleven years after the end of the AAPF and the ALPF, C. P. Hurditch relates that as a result of “the base ball leagues” thinking “the time was ripe to exploit the game,” soccer in Philadelphia “received such a shock that it took years to recover”; so “weakened and disorganized” was amateur soccer by the “natural consequences” of the appearance of professionalism that it looked as if soccer “had died a natural death.” In making his argument, Hurditch conflates the two professional leagues, writing that the “base ball leagues” had “placed four professional teams in the field,” the number the AAPF began with, not the six that competed in the ALPF. More importantly, Hurditch greatly overstates the impact of the first appearance of professional leagues in the U.S. on soccer’s wider development; the economic fallout of the Panic of 1893 had begun to affect the health of the PAFU before the appearance of the AAPF and the ALPF and the consequences of the economic crisis would eventually be a factor in the suspension of the American Cup tournament after its 1897-1898 edition until its revival in 1906. But he is correct in identifying why professional league soccer did not succeed in its first appearance in the U.S.: “the public did not sufficiently appreciate the fine points of the game, attendance and gate receipts were not such as would warrant the keeping of the high-salaried players that had signed.”[82]

Hurditch was not alone in attributing too much cause for soccer’s decline in the United States in the second half of the 1890s to professionalism. Writing in 1910, C. K. Murray asserts that when professionalism “crept” into New York- and New Jersey-based clubs at the end of the 1890s, the AFA was “unable to cope with the predatory efforts of the prominent clubs to secure crack players” and “threw up the sponge.” Left unanswered is why the AFA was now unable to “cope” with professionalism when it had been present for at least a decade. In his explanation for why the American Cup tournament had been suspended, Murray actually provides the real answer for the AFA’s decline in the second half of the 1890s: “Owing to strikes in the Fall River district, throwing thousands of men idle, the ‘Down East’ clubs were forced to withdraw from the competition and foot ball in that section was practically killed.”[83] Again, larger economic conditions, not professionalism, were at the root of the AFA’s troubles. By the middle of the first decade of the 1900s, the U.S. economy had recovered from the lingering effects of the Panic of 1893 and soccer, aided by the visit of touring English teams the Pilgrims and the Corinthians, was rebounding from the dark days at the end of the previous century.

Accompanying soccer’s resurgence in the U.S. in the first decade of the twentieth century were continuing concerns about the effect of professionalism. In Philadelphia, for example, the Pennsylvania League had been founded in 1902. By 1907, Douglas Stewart complained, “unfortunately professionalism has crept into a number of the good teams,” although “steps to eliminate this evil” were being taken by the Football Association of Philadelphia.[84] In New York, the demise of the Metropolitan League was blamed on “bad management and semi-professionalism.”[85] Professionalism wasn’t just an East Coast phenomenon. The professional St. Louis Soccer Football League organized in 1907.[86]

Seven years after bemoaning the creeping evil of professionalism, Stewart wrote, “In the government of the professional teams there exists little or no harmony.” Professional teams cared only for their own interests irrespective of other clubs or even the promotion of soccer itself. The grounds of professional teams “as a rule” were small and lacking in “conveniences essential to comfort.” Not only that, “a great many of the spectators indulge in exhibitions of conduct and language which are even more disagreeable than the ground conditions.” Professional players engaged in bad conduct themselves, with “rowdy, unskillful players” getting into fights when their team suffered defeat.”[87] Of course, all of the faults Stewart attributes to professionalism — self-interest, disharmony, poor grounds, rowdy fans and players — also existed in amateur soccer. Nevertheless, attempts to quash professionalism were doomed to fail. After the American Cup resumed in 1906, professional teams dominated the tournament, as was the case after the founding of the U.S. Open Cup in 1913. American Cup stalwarts were members of the short-lived professional Eastern League, organized in 1909 and made up of six teams from Northern New Jersey, Philadelphia, and Fall River-Pawtucket, the leading soccer centers on the East Coast. When the National Association Football League was re-formed in 1907, it was a semi-professional league. Indeed, dissatisfaction with the semi-professional nature of the league eventually contributed to the formation of the fully-professional American Soccer League in 1921. Stewart’s moralizing aside, his concern about the lack of harmony among professional teams was a question of effective governance and mediation of inevitable disputes. The ineffectiveness of the AFA, and the geographic restrictions of its power whatever its claims as a national authority, were prime factors in the creation of the United States Football Association (USFA) in 1913. The debate over just how effective the USFA, known now as the United States Soccer Federation, has been in managing and promoting professional soccer continues to this day.

The ALPF offered two reasons for its demise: the late start to the season because of the “prolongation of the baseball season” due to the postseason Temple Cup series, and the “difficulty in avoiding conflict with the regular college football games.” Rumors of the emergence of a rival professional baseball league, the American Association of Base-Ball Clubs, formalized at a meeting in Philadelphia at the Colonnade Hotel the same day the ALPF voted in New York to close the league, also must have distracted the attention — and resources — of the National League baseball magnates.[88] But one “prominent member” of the ALPF made clear the league was simply losing too much money: “over $2,000 had been lost” and “total gate receipts of the games played in the various cities did not exceed $25.”[89] Another report said Philadelphia “received $9.22” for two games in Brooklyn and $60 for two games in Washington D.C.[90] Such numbers surely were not what Arthur Irwin had in mind when he hatched his “scheme.”

Irwin may have been impressed that “between 400 and 500” people came out after a “violent snow storm” to see the draw between All-Philadelphia and the Cosmopolitans, and he most certainly was impressed when between 2,000 and 3,000 spectators, “including many women,” saw All-Philadelphia defeat the Cosmopolitans, 4-0, a month later to claim the inter-city championship.[91] While below the average attendance for the Philadelphia Phillies baseball season that year, it was within the range between the average attendance of Boston and Brooklyn.[92] But the All-Philadelphia-Cosmopolitans series was a marquee matchup, an inter-city championship event played on holidays when workers had the day off, and such numbers were not commonplace in other PAFU games. Even if support for the Philadelphia ALPF team was complicated by the existence of another professional soccer team in the city, the largest reported attendance for a Philadelphia ALPF home game — 525 — was probably more in line with what could be reasonably and regularly expected.[93] Quite simply, soccer at this time, whatever its promise, was a niche sport played and supported largely by British immigrant industrial workers, and was comparatively unknown to the wider public. An indication of this can be found in previews of the league published in The New York Times and The Washington Post. Under headlines like “Football with the Feet” and “Under New Rules,” much of the previews consist of explanations of the rules of soccer for a readership unfamiliar with the game.[94]

While Ned Hanlon, manager of the Baltimore team that was undefeated in three games after their late start in the league, absurdly suggested, “other clubs gave up the ghost because they believed that they had no chance to defeat Baltimore,” Washington D.C. owner Earle Wagner said only he and Irwin wanted the league to continue. According to Wagner, who also said he viewed the ALPF’s inaugural season as “a season of education,” presumably as much for the owners as for the fans, the issue for New York and Brooklyn wasn’t that the clubs were “losing a little money” — hard to believe considering each team reported attendance of 50 and 18, respectively, the day the league decided to close — but that the Polo Grounds and Eastern Park had already been rented “for many days of college football and other outdoor sports,” resulting in unsolvable scheduling conflicts.[95]

The ALPF’s scheduling issue was multifaceted. An extended schedule was not released until a week after its opening games, and that schedule only covered games through October 23, affecting the planning of both teams and fans.[96] The league’s decision to play weekday games, as predicted by the AAPF’s Hackett, unsurprisingly also did not deliver the expected revenue; soccer’s existing fan base was still at work in factories and mills when weekday ALPF games kicked off. Bad weather meant postponed games had to be squeezed in between already scheduled games, which resulted in additional hotel expenses; baseball-style doubleheaders would not work in the fall and winter months when night fell early and no team could be expected to play three hours of competitive soccer.

The widespread use of non-local players also inhibited easy connections between newly minted ALPF teams and the local soccer fan bases that ought to have been the foundation of the league’s support. While the burgeoning controversy over Baltimore’s importation of professional soccer players from Britain — the players imported from Detroit didn’t begin training in Baltimore until October 11 — and the threat of a new rival professional baseball league did not help matters, the unnamed “prominent member” also made sure to condemn the ALPF for ignoring the AFA, which resulted in ill will from the existing soccer community and the AFA ban. Further underscoring the point, the unnamed informant said the laws and rules in the league’s constitution “showed plainly that the compilers knew very little about their business.”[97]

In some ways the ALPF was prescient: the use of substitutes and the intercontinental recruitment of players were years ahead of their time, and Major League Soccer utilized the reserve clause until the introduction of restricted free agency in the 2015 collective bargaining agreement with the MLS Players Association, nineteen years after the league’s first season. But in so many other ways the ALPF completely missed the mark. Fans in Baltimore “complained that they could not tell when a goal was made”; the goalposts had not been painted white so the posts on one end of the field blended into the center-field fence. The absence of a scoreboard also meant fans had trouble keeping track of the score.[98] In Brooklyn, the playing field was not roped off, which meant “a dozen or so of New York’s finest” were needed to keep spectators off the pitch.[99] “Considerable trouble” arose when New York hosted Boston and the league failed to appoint a referee for the game.[100] The absence of nets for the goals in Washington meant a goal claimed by the home team against Philadelphia was not allowed because the referee wasn’t in a position to see if the ball went under or over the crossbar.[101] In fundamental matters of timing, organization, and management, the ALPF failed as a professional association and in retrospect, the prospects of the league were doomed from the start. This is not a verdict only made possible in hindsight after the passage of 125 years. The World predicted in March only days after plans for the league were first reported that the ALPF would “probably be a failure” because its schedule conflicted with the college football season “and Association football no more compares with the college game than beanbag does with baseball,” while a report in The Sporting Life a week after the league’s demise came under the headline, “As Was Expected.”[102]

The AAPF did not announce it was folding after the Paterson-Kearney Unions games in December. Rather, the league seems to have simply withered away. Handicapped from the start in failing to field six teams as was announced in August, that New York and Brooklyn sides did not join the league as expected fatally wounded its prospects. This was compounded by Trenton’s early exit: with only three teams to compete against one another, one team necessarily would be idle every Saturday. Reported attendance numbers for AAPF games are few, but one poorly attended game here, another postponed-by-weather game there, would quickly add up to a severely challenged bottom line despite the league’s best efforts to minimize costs. Professional baseball team owners had the resources to cover player wages despite unexpected costs and flagging attendance, even if most soon lost the will to do so. The manager of the Philadelphia AAPF team and president of the AAPF, Clement Beecroft, owned a sporting goods store, the team’s president was a newspaper sports editor. Arthur Goldthorpe was president of the Paterson True Blues before being elected president of the Paterson League team but he was an “expert designer in the silk mills” by trade.[103] All well-paid positions, perhaps, but unlikely to provide Beecroft, Fogel, and Goldthorpe with deep enough pockets to continue to pay players’ wages as the prospect for league games diminished along with the league’s roster of teams. With the AFA ban in effect, the possibility of other teams joining the league was slim at best and a spring season was not organized.

Instead, soccer leaders in New York and Northern New Jersey organized the National Association Football League (NAFL) in December 1894, with games to be played on Sundays and holidays. By 1897, teams from Kearny, Newark, and Paterson made up the bulk of the NAFL’s roster before economic conditions led to its suspension in 1899.[104] At its first executive meeting in February 1895, NAFL leaders considered “the question of disbarring the men who took part in the games of the defunct National Association of Professional Football Clubs”: the ALPF. “The matter was fully discussed, and it was finally agreed not to take action to prevent them from playing, so they can become members of league clubs.” However, no player could “receive remuneration in any manner for playing, outside of traveling expenses.”[105] Former ALPF players would still be ineligible to participate in the American Cup until the AFA lifted its ban. That the AAPF was also not named in the announcement suggests hopes for a spring season may have still remained at this time; at the very least, it is recognition that the Kearney Unions and Paterson League teams still existed.

The AAPF undeniably made better decisions than the ALPF in basing teams on local talent, recognizing the domestic realities of both its players and fans in arranging a Saturday schedule and in limiting its geographic footprint. But both the AAPF and the ALPF made the same error in concluding a professional league was now sustainable in the United States, particularly in the midst of an economic depression. However fervently British immigrants might have supported the game, it had not penetrated the minds of the wider sport-loving, native-born masses, for whom soccer remained an unfamiliar sport and whose attention in the fall months was firmly directed toward college football. The failure of both leagues was not a “golden opportunity wasted” but the result of a miscalculation that placed soccer’s potential in the U.S. ahead of its reality.[106] The sustainability of professional soccer in the United States would be questionable for decades to come, but this was not because of the failure of the AAPF and ALPF. Writing twenty years after the first professional leagues during a boom period for soccer in the U.S., Douglas Stewart observed, “nowhere in the United States is the game sufficiently developed or popular to warrant the establishment and maintenance of a professional team in the sense, say, of a major league base ball team.”[107] So it would remain for much of the next one hundred years.

After the professional leagues

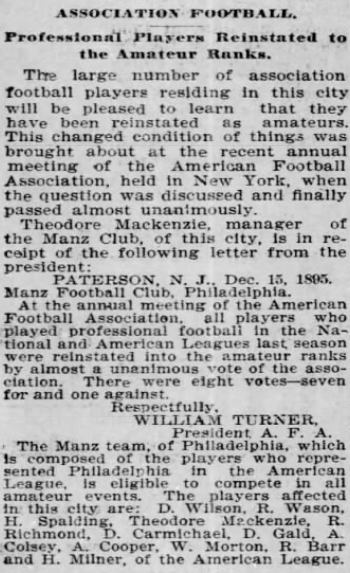

The three remaining AAPF teams — the Kearney Unions, the Paterson League team, and the Philadelphia team — did not face one another after the 1894 season. The Kearney Unions consolidated with the Kearney Rangers in November 1895 and by the spring of 1896 were playing as the Kearney Athletics.[108] After considering a tour of Canada, and later losing to Paterson True Blues, 4-1, in a game to decide the champion of New Jersey, the Paterson League team disbanded before the start of the 1895-1896 season and its players joined other local teams.[109] The Philadelphia team became the John A. Manz team, named after its sponsor, the treasurer of the Philadelphia Brewing Company.[110] On December 15, 1895, the AFA voted to reinstate the amateur status of “all players who played professional football in the National [ALPF] and American [AAPF] Leagues last season,” making them eligible to participate in the AFA’s American Cup tournament.[111] Twelve Manz players were among those reinstated. The letter the Manz team received announcing the lifting of the ban was signed by William Turner, the president of the AFA and former manager of the Paterson League team.

On Christmas Day 1896, the Manz team hosted Kearney Athletics in a friendly at the Stenton Grounds at Wayne Junction. Only one Kearney player had been on the field for the Philadelphia-Newark AAPF game on November 13, 1894 — Alfred Cutler, one of the players who had broken his contract with the New York ALPF team to rejoin the Kearney Unions — but five of the Manz players had appeared in that game for Philadelphia. It was “a bitterly fought contest” and the Athletics play “was not as clean as it might be.”[112] At the final whistle, Kearney was the 3-1 winner. It was Manz’s first ever loss in Philadelphia over a stretch of two years, their only previous loss coming on the road at Cosmopolitan Park to reigning American Cup champions Newark Caledonians on December 21, 1895, in a game that included five former Philadelphia AAPF players and two former Kearney Union players.[113]

Manz, Newark Caledonians, and Kearney Athletics all entered the 1896-1897 American Cup tournament, the first round of which began at the end of October. Also competing were the reigning American Cup champions, the Paterson True Blues, whose former president, Arthur Goldthorpe, was back with the club after his stint as the president of Paterson League team. The True Blues’ delegate to the American Football Association, Goldthorpe was elected AFA president in September 1896.[114]

The True Blues advanced to the American Cup finals after dispatching Connecticut-side Taftsville and the Kearney Athletics, the series against the Athletics being overshadowed by protests and replayed games.[115] In March 1897, a rumor was reported that “the old National Football Association” — the ALPF — was about to be “resurrected,” with “two of the former projectors and directors…making an effort to form a league in several large Eastern cities,” but nothing came of the rumors.[116] Manz advanced to the finals after moving past Newark Caledonians and Clark O.N.T.[117]

The 1896-1897 American Cup final ended up being played over four games: Manz hosted and won the first game, 4-2, at Wayne Junction on April 24, 1897.[118] At Willard Park in Paterson on May 3, the True Blues won 3-1 to force a third game.[119] On neutral ground at Metropolitan Park in Newark on May 8, the teams played to a 2-2 draw, forcing a fourth game at Cosmopolitan Park on May 22, 1897.[120] Over 5,000 spectators were on hand as the teams entered halftime level at 1-1. With twenty minutes remaining in the game, Paterson scored again for a 2-1 lead before Manz scored four goals in quick succession to finish 5-2 winners and American Cup champions. As had been the case when the Philadelphia and Paterson AAPF teams met in Philadelphia in 1894, Manz had come from behind to equalize after Paterson scored first, conceded another goal before equalizing again, and then ran away with the game with a barrage of goals for an emphatic victory. Five of the Manz players in the final were former Philadelphia AAPF players. Four of the True Blues players had been on the Paterson League team. The Amateur Athlete, the official publication of the AFA, called it “the greatest game of Association football ever witnessed in America.”[121]

For more on the AAPF and ALPF, see Philadelphia and the other first professional soccer league in the U.S. (2015) and After the collapse: ALPF vs. ALPF in Baltimore and Fall River, 1894-96 (2020)

For more on the AAPF and ALPF, see Philadelphia and the other first professional soccer league in the U.S. (2015) and After the collapse: ALPF vs. ALPF in Baltimore and Fall River, 1894-96 (2020)

Notes

[1] Ed Farnsworth, “Philadelphia and the other first professional soccer league in the U.S.” Society for American Soccer History, accessed June 4, 2018. https://www.ussoccerhistory.org/philadelphia-and-the-other-first-professional-soccer-league-in-the-u-s/

[2] David Goldblatt, The Ball is Round: A Global History of Football (London: Viking, 2006), 45-46.

[3] Goldblatt, 54-57.

[4] Melvin Smith, Evolvements of Early American Foot Ball (Bloomington: AuthorHouse, 2008), 165.

[5] Ed Farnsworth, “Philly and the New York Cosmopolitans,” The Philly Soccer Page, accessed June 4, 2018. http://www.phillysoccerpage.net/2014/06/18/philly-and-the-new-york-cosmopolitans/

[6] “Irwin Springs Another Scheme,” The Philadelphia Inquirer, February 24, 1894, 3; “Football Among Ball Players,” Pittsburgh Dispatch, November 25, 1890, 6.

[7] “Professional Football,” The Philadelphia Inquirer, June 20, 1894, 3.

[8] “The Ball Park a Heap of Ashes,” The Philadelphia Inquirer, August 7, 1894, 1,7; “1900 Persons Homeless,” The Boston Daily Globe, May 16, 1894, 1,4, 7.

[9] “Association Football,” The Boston Daily Globe, October 8, 1894, 7.

[10] “Professional Football,” The Philadelphia Inquirer, June 20, 1894, 3.

[11] “Professional Football,” The Boston Daily Globe, September 18, 1894, 18; “Under the New Rules,” The Washington Post, October 8, 1894, 6; Holroyd, 18.

[12] “Obituary: George E. Stackhouse,” New York Daily Tribune, January 31, 1903, 7; “Professional Football,” The Philadelphia Inquirer, August 15, 1894, 3.

[13] “Professional Football,” The Boston Daily Globe, September 8, 1894, 5

[14] “Professional Football,” Idaho Daily Statesman, August 18, 1894, 5.

[15] Steve Holroyd, “The American League of Professional Football, 1894,” Soccer History (Spring, 2006), 18; Peter Morris, A Game of Inches: The Stories Behind the Innovations That Shaped Baseball (Chicago: Ivan R. Dee, 2010), 498-500; Steve Holroyd, ”The First Professional Soccer League in the United States: The American League of Professional Football (1894), American Soccer History Archives, Last updated September 4, 2000, accessed June 4, 2018.

[16] Holroyd, 19.

[17] “Footballists Convene,” Newark Sunday Call, September 16, 1894, 6.

[18] “Oppose League Football,” The Boston Daily Globe, September 17, 1894, 2.

[19] “Footballists Convene,” 6.

[20] “Professional Football,” The Boston Daily Globe, September 8, 1894, 5; “Professional Football,” The Boston Daily Globe, September 18, 1894, 18; “Football With the Feet,” The New York Times, October 7, 1894, 21; “They Will Represent Philadelphia,” The Times (Philadelphia), September 26, 1894, 9; “Washington’s Englishmen,” The Boston Daily Globe, October 1, 1894, 5; “Association Football Stars,” The Boston Daily Globe, October 1, 1894, 5.

[21] “Sporting News and Comment,” The Washington Post, October 10, 1894, 6.

[22] “Two More Football Men,” The Boston Daily Globe, September 15, 1894, 2; “Washington’s Englishmen,” 5; “General Sporting Notes,” The Chicago Daily Tribune, October 17, 1894, 11; “Comment About Various Sports,” The Philadelphia Inquirer, October 14, 1894, 24; “Imported Professional Players,” The Public Ledger, October 20, 1894, 19; “An Alleged Violation of Law,” The Times (Philadelphia), October 20, 1894, 8.

[23] “Byrne’s Foot Ball Team,” The Brooklyn Daily Eagle, October 7, 1894, 8; “Washington’s Englishmen,” 5. For more on Dennis Shea’s soccer career, which ended after his time in the ALPF, see Grant Czubinski,”Dennis Shay: Patriarch of American Goalkeepers,” A Moment of Brilliance, accessed June 4, 2018. http://amofb.blogspot.com/2016/02/dennis-shay-americas-goalkeeper.html

[24] “American Football Association,” The Morning Call (Paterson), September 18, 1894, 5.

[25] “Foot Ball,” The Public Ledger, August 25, 1894, 15.

[26] “Howard Hackett Dead,” The Buffalo Courier, May 1, 1897, 1.

[27] “The Realm of Sport,” Paterson Daily Guardian, October 2, 1894, 1; “A New Football League,” The Morning Call (Paterson), October 2, 1894, 8.

[28] “Personnel of the Philadelphia Foot Ball Team,” The Public Ledger, September 28, 1894, 15;

[29] “Foot Ball,” August 25, 1894, 15.

[30] “Association Football,” Newark Sunday Call, September 16, 1894, 6; “True Blues are Champions,” Paterson Daily Guardian, March 26, 1894, 1; “Association Football,” The Amateur Athlete, February 25, 1897, 6-8; “Today’s Football Game,” The Morning Call (Paterson), December 16, 1893, 8; “Muscular Christianity,” New York Herald, May 1, 1892, New Jersey Supplement. Throughout this paper I use the spelling most commonly used at the time for the Kearney Unions rather than the spelling that would be correct today, Kearny.

[31] “Personnel of the Philadelphia Foot Ball Team,” 15.

[32] “General Sporting Notes,” The Public Ledger, September 4, 1894, 13.

[33] “Foot Ball,” August 25, 1894, 15; “Personnel of the Philadelphia Foot Ball Team,” 15; “Association Football,” The Philadelphia Inquirer, September 30, 1894, 3; “Association Foot-Ball,” The Times (Philadelphia), September 30, 1894, 16; “Association Foot Ball,” The Public Ledger, October 1, 1894, 15; “Local Cricketers are Snowed Under,” The Philadelphia Inquirer, September 30, 1894, 2.

[34] “Sports and Pastimes,” Paterson Daily Press, October 1, 1894, 1.

[35] “The Realm of Sport,” 1; “A New Football League,” 8.

[36] “Cosmopolitans to Visit Canada,” The New York Times, October 14, 1894, 14; “Meeting of the Cosmopolitan Football Association, The Sun (New York), October 14, 1894, 7.

[37] “Football Games and Gossip,” The New York Times, October 24, 1894, 3; “Sporting Miscellany,” Paterson Daily Guardian, November 1, 1894, 1.

[38] “Association Foot Ball,” The Public Ledger, October 1, 1894, 15; “Association Football,” The Philadelphia Inquirer, October 2, 1894, 3; “Association Football,” The Philadelphia Inquirer, October 3, 1894, 3.

[39] “New York Takes One,” The Philadelphia Inquirer, October 7, 1894, 3; “Association Foot Ball,” The Public Ledger, October 8, 15; “Boston Begins Well,” The Boston Daily Globe, October 7, 1894, 16.

[40] “American Association,” The Public Ledger, October 8, 1894, 15; “General Sporting Notes,” The Public Ledger, October 12, 1894, 15.

[41] “A Lantern Parade,” The Morning Call (Paterson), October 9, 1894, 1.

[42] “Sporting News and Comment,” The Washington Post, October 9, 1894, 6.

[43] “Won by Washington,” The Washington Times, October 12, 1894, 3; “Washington, 2; Philadelphia, 1,” Brooklyn Daily Eagle, October 12, 1894, 4.

[44] “Football Games and Gossip,” The New York Times, October 13, 1894, 6; “Sporting News and Comment,” The Washington Post, October 17, 1894, 6.

[45] “Shut Out by Brooklyn,” Brooklyn Daily Eagle, October 16, 1894, 5; “Brooklyn 1, New York 0,” The Boston Daily Globe, October 16, 1894, 2.

[46] “Hanlon’s Kickers,” The Baltimore Sun, October 19, 1894, 6; “Association Football Games,” The Washington Post, October 19, 1894, 6; “Association Football,” The Philadelphia Inquirer, October 19, 1894, 3; “Sporting Miscellany,” The Boston Daily Globe, October 20, 1894, 5; Sam Foulds and Paul Harris, America’s Soccer Heritage: A History of the Game (Manhattan Beach: Soccer For Americans, 1979), 14; Holroyd, ”The First Professional Soccer League in the United States: The American League of Professional Football (1894), American Soccer History Archives, Last updated September 4, 2000, accessed June 4, 2018; “Brooklyn 3, Philadelphia 1,” The Boston Daily Globe, October 19, 1894, 3; “Boston 4, New York 3,” The Boston Daily Globe, October 19, 1894, 3.

[47] “General Sporting Notes,” October 12, 1894, 15.

[48] “General Sporting Notes,” The Public Ledger, October 17, 1894, 19.

[49] For Cutler and McGee on the Kearney Unions roster before signing with the New York ALPF team see “True Blues Are Champions,” Paterson Daily Guardian, March 26, 1894, 1; Holroyd, 20. The reference in Holroyd’s article incorrectly states it was the Philadelphia ALPF team that played the Kearney Unions.

[50] “General Sporting Notes,” The Public Ledger, October 15, 1894, 15

[51] “The Game at Tioga,” The Times (Philadelphia), October 14, 1894, 8.

[52] “General Sporting Notes,” October 15, 1894, 15.

[53] “An Error Corrected,” The Times (Philadelphia), October 16, 1894, 8.

[54] “Football Games,” The Morning Call (Paterson), October 15, 1894, 8.

[55] “Gate Receipts $25,” The Boston Daily Globe, October 21, 1894, 4.

[56] “Association Football,” The Philadelphia Inquirer, October 21, 1894, 3; “Miscellaneous Sporting Notes,” The Washington Times, October 21, 1894, 1.

[57] See for example, “Gate Receipts $25,” 4; “The Professional Football League Disbands,” The Sun (New York), October 21, 1894, 11; “Professional Football Is Dead,” The New York Herald, October 21, 1894, 10.

[58] “Football Games,” October 15, 1894, 8; “The Sporting News,” The Morning Call (Paterson), October 17, 1894, 8; “Y.M.C.A. Bowlers,” The Morning Call (Paterson), April 12, 1895, 8.

[59] “The Leaders Meet on Sunday,” The Times (Philadelphia), November 9, 1894, 8; “Meeting of the Two Leaders,” The Public Ledger, October 9, 1894, 15.

[60] “Tackles and Touchdowns,” Newark Sunday Call, October 21, 1894, 6; “Association Clubs Meet,” Paterson Daily Guardian, December 3, 1894, 1. During the same meeting in which the AFA dismissed Centreville’s complaint against the Kearney Unions, it upheld a similar complaint from the Fall River Olympics against the Pawtucket Free Wanderers. The report provides no details but it is a reasonable speculation that Pawtucket used former ALPF players — the Boston ALPF team had several Pawtucket players — who were freed from their contracts on November 1.

[61] “Easy for the Philadelphias,” The Times (Philadelphia), October 28, 1894, 8.

[62] “On Rugby Chalk Lines,” Paterson Daily Guardian, November 5, 1894, 1.

[63] “Professional Football,” The Philadelphia Inquirer, November 1, 1894, 6; “The League vs. American Association,” The Times (Philadelphia), November 1, 1894, 10.

[64] “The Weather,” The Philadelphia Inquirer, November 4, 1894, 1.

[65] “The Professional League Disbands,” The Sun (New York), October 21, 1894, 11.

[66] “General Sporting Notes,” The Public Ledger, November 15, 1894, 15; “The Professional Kickers Disband,” The Baltimore Sun, November 21, 1894, 6. For more on the Baltimore, Boston, Brooklyn, and Philadelphia ALPF teams after the demise of the ALPF, see Ed Farnsworth, “After the Collapse: ALPF vs. ALPF in Baltimore and Fall River,” Society of American Soccer History, https://www.ussoccerhistory.org/after-the-collapse-alpf-vs-alpf-in-baltimore-and-fall-river-1894-96/

[67] “The Leaders Meet on Sunday,” 8.

[68] “Philadelphia vs. Paterson,” The Public Ledger, October 10, 1894, 19.

[69] “Some Good Bowling,” The Morning Call (Paterson), November 10, 1894, 1; “Professional Football,” The Philadelphia Inquirer, November 11, 1894, 5.

[70] “General Sporting Notes,” The Public Ledger, November 16, 1894, 15.

[71] “To Play the Tigers,” The Times (Philadelphia), November 20, 1894, 8; “College Association Football,” The New York Tribune, November 23, 1894, 3; “General Sporting Notes,” The Philadelphia Inquirer, November 24, 1894, 4. Holroyd incorrectly says it was Irwin’s Philadelphia ALPF team that accepted the “Princeton” challenge. See Holroyd, 22.

[72] “Association Foot-Ball,” The Alumni Princetonian, December 11, 1895, 3.

[73] “Princeton is Beaten,” The Philadelphia Inquirer, November 25, 1894, 4; “Princeton Was Not In It,” The Times (Philadelphia), November 25, 1894, 8.

[74] “Paterson vs. Cosmopolitans,” The Morning Call (Paterson), November 21, 1894, 8; “Among the Sports,” The Morning Call (Paterson), November 27, 1894, 1.

[75] “Y.M.C.A. Bowlers,” 8.

[76] “Football All About,” Newark Sunday Call, November 4, 1894, 6; “Among the Sports,” 1.

[77] “Excelsiors in Two,” The Morning Call (Paterson), December 22, 1894, 8.

[78] “Local Teams Win,” The Morning Call (Paterson), December 24, 1894, 1; “Entre Nous Wins,” The Morning Call (Paterson), December 26, 1894, 8.

[79] “Meeting of the Two Leaders,” The Public Ledger, November 9, 1894, 15; “Philadelphia, 7; Paterson, 2,” The Public Ledger, November 12, 1894,19.

[80] “Football,” The Morning Call (Paterson), April 26, 1895, 1.

[81] “Another Pennant,” The Baltimore Sun, October 22, 1894, 7

[82] C. P. Hurditch, “Association Football,” Association Foot Ball Guide, ed. Jerome Flannery (New York: American Sports Publishing Company, 1905), 7-9.

[83] C. K. Murray, “History and Progress of the American Football Association,” Spalding’s Official Association “Soccer” Foot Ball Guide, 1910 (New York: American Sports Publishing Company, 1910), 31.

[84] D. Stewart, “Development in Philadelphia,” Spalding’s Official Association “Soccer Foot Ball Guide, ed. Henry Philip Burchell (New York: American Sports Publishing Company, 1907), 52-53

[85] John R. Bolton, “Soccer Foot Ball in America,” Spalding’s Official Association “Soccer” Foot Ball Guide, 1909 (New York: American Sports Publishing Company, 1909), 7.