Inside the Irish American Club in Kearny, New Jersey, and in between sips of his Guinness stout beer, Hugh O’Neill sits on a stool and talks about June 1966 as if it were yesterday.

His beloved Celtic Football Club of Glasgow, Scotland visited the member’s only social club during a summertime tour, and thirteen-year-old Hughie met his sporting heroes in the flesh.

“I stood outside the front door on Kearny Avenue and got them all to autograph a team photo. When they beat a New Jersey select team at Kearny High School, 5-1, in front of 7,500 fans, I was the ball boy,” he recalled. “Jimmy Johnstone was my idol, but he didn’t play that day because he had horrible sunburn. That tour helped build a team that went on a great run.”

Celtic supporters call that magical 1966-67 season “The Quintuple” as a side made up of players all from within a thirty-mile radius of Celtic Park won five different competitions, including the league, league cup, Scottish Cup, Glasgow Cup, and, most importantly, the European Cup.

Celtic became the first British team to lift the prestigious trophy when they toppled Inter Milan at Lisbon’s National Stadium. They have been called “The Lisbon Lions” ever since. The barroom at “The Irish” still pays tribute to those green and white heroes of forty-five years ago: a replica of the European Cup sits behind the bar, and pictures of the historic team hang on the walls.

O’Neill knows his Celtic F.C. history—he can still rattle off the starting eleven from 1967—but few people know that he is part of a little known chapter in Scottish soccer history.

In 1976, after his first year in the North American Soccer League, twenty-one-year-old Hugh went on loan to Celtic’s bitter crosstown rival, Rangers Football Club. Although Maurice “Mo” Johnston is often recognized as the first “known” Catholic to play for Rangers when he signed in 1989, Hugh O’Neill was really the first. If Hugh had broken into the first team during his six-month spell at the Glasgow club, he would surely be recognized as one of soccer’s great trail blazers.

Nearly ten years ago the Edinburgh-based newspaper, The Scotsman, ran a story on O’Neill’s place in Scottish soccer history, and journalist Alan Patullo suggested that if O’Neill authored a book it could be called: A Divide Wider Than the Atlantic: How a Celtic-Supporting American Catholic Ended Up at Glasgow Rangers.

“A Divide Wider Than the Atlantic”

Recognized as one of the fiercest sport rivalries anywhere, “The Old Firm” has deep divisions along religious (Catholic Celtic and Protestant Rangers), political (Republican Celtic and Loyalist Rangers), and class lines. The rivalry is also one of the world’s most violent.

Not surprisingly, some of those same problems crossed the Atlantic Ocean when Scottish and Irish immigrants settled in Kearny and Harrison. In order to understand Hugh O’Neill’s controversial return to his ancestral homeland in 1976, one has to appreciate the neighborhood he grew up in. In doing so, his short stint at Rangers makes a bit more sense.

Like so many other Celtic supporters, young Hughie was born into, nay baptized into, a sporting rivalry. He inherited his love of Celtic from his father, Hugh, Jr., a British war veteran who came to the United States in 1948. He soon found work as a bricklayer, and played semi-professional soccer for the American Soccer League’s Brooklyn Hispano and Kearny Irish. While Hugh’s three older sisters were born in Scotland, Hugh and his little sister were both born in Kearny. His mother worked as a waitress. The family settled in a lower Kearny neighborhood called Cooper’s Block, which had housed generations of new arrivals from Scotland and Ireland.

Cooper’s Block was also one of America’s first soccer neighborhoods. Local men formed teams as early as 1878. By 1883, Clark Thread Mill, one of three massive mills in the area, formed its own athletic association, O.N.T., after its slogan “Our New Thread.” A company soccer team played in an enclosed field shortly after (it’s now the site of a typical Jersey diner) and soon became the first American soccer dynasty, winning three-straight American Football Association cups beginning in 1885.

Other teams formed, too, namely the Kearny Rangers and the West Hudsons. Some of America’s greatest players have come out of the neighborhood, starting with four men who played on the first-ever United States national team in 1916. (Jim “Bow” Ford, John “Rabbit” Hemingsley, Harry “Buck” Cooper, and George Tintle started a long line of USMNT stars as Kearny’s John Harkes and Tony Meola, and Harrison’s Tab Ramos represented the United States at the 1990 and 1994 World Cups.)

As more and more immigrants streamed into the industrial towns of Kearny and Harrison, the lines that divided Glasgow for centuries began to take shape in the Hudson County hamlets. From the early 1900s, lower Kearny and mile-square Harrison were predominantly Irish, Catholic, and working-class. Harrison was also a Democratic Party stronghold.

Kearny, much of it situated on what cartographers called “The Highlands,” was almost the opposite: Scot-Presbyterian folks who were better off and supported the Republican Party. By the early 1930s, both constituencies had local clubs to support, as well as their very own version of the Old Firm.

At the start of the 1932 season, the Scots-Americans, based out of the months-old Scots American Athletic Club on Patterson Street, squared up against local rival, the St. Cecelia Soccer Club. Based out of the Roman Catholic Church on Kearny Avenue — where young Hughie would be baptized and later went to grade school — St. Cecelia S.C. became the Kearny Irish when the Irish American Club formed in 1933.

“Some 2,000 fans sat in the stands watching the initial game of the season at Clark’s Field and were deeply surprised to not only see the St. Cecelians win but shut out their strong rivals,” noted the Newark Star-Eagle reporter. “Time and again the bitterness between the elevens caused Referee Coggins to warn players. Three players were banished for fighting.” It was a typical Old Firm match, but in Kearny.

That day was also one of Bob Campbell’s earliest memories. After a contested call, some one hundred men stormed the field and brawled with one another. “I remember bawling my eyes out in the stands as my grandfather, my father, and his three brothers joined the fray. I thought I’d never see them again,” recalled the Kearny native.

The local Old Firm matches were always the highlight of the soccer calendar. Jim Mays, a star midfielder for the Scots during the 1960s, remembers those games being about more than just pride. “There was a lot of money bet on those games. Bets were placed in the Irish and Scots clubs before the game,” he said. “One time the Irish sent down $1,200. The Scots players couldn’t cover it so the men from the Masonic Lodge covered the bet, using the money from the treasury.” For sports fans out there who want to bet on their teams, they can now do it online with sbobet ทางเข้า.

“Those games were great to play in,” added Mays. “Players flew into tackles, and there was all sorts of banter. You knew which ones to call names to get into their heads.”

In 1966, Mays, a Protestant player for the Scots, wasn’t considered for the select team to play against Celtic F.C. during their summer tour. “The Irish picked that team, and I never got picked. I wasn’t even given consideration,” he recalled. And, he was among the best midfielders in the league. In 1967, Mays was a victim of Celtic’s European success. He was sold to another local club, the Newark Germans, for $800 because his manager wanted to use the transfer money to travel to Lisbon to see the final.

From Soccertown U.S.A. to the NASL

Hugh O’Neill, III’s earliest soccer memory is not one of fear, but one of disappointment. When his father started a recreational soccer league in 1961, a league started two years before the American Youth Soccer Organization (AYSO), young Hughie couldn’t wait to play, even if he was two years too young. His rule-abiding father forbade him to play, and made his son hand out team uniforms from the back of the family pick-up truck instead.

The teams were named after some of the area’s greats, including Archie Stark, the all-time American Soccer League leading scorer; Fred Shields, a 1936 Olympian; and Davey Brown, a diminutive winger who also starred in the ASL. By the time Hughie joined two years later, team names changed to clubs from the Scottish First Division. “It had been worth the wait,” said a smiling O’Neill. “I got to play for Celtic.”

Hugh went on to star for Kearny United, one of the first youth club teams in New Jersey, as well as the Scotch Juniors and then the Scots American Club. When he played for the Juniors, he met Peter Millar, a Scottish-born U.S. international. Millar had played for Argentina’s Boca Juniors who passed on the art of finishing to the young O’Neill.

Moreover, like many players in Kearny and Harrison, Hugh honed his game in a vibrant street soccer scene, namely at the tennis courts in Harrison and in a street hockey arena at Kearny’s Emerson School. They were rough-and-tumble affairs where skill, smarts, and toughness mattered in “winner-stays-on” pick-up games. Dave D’Errico, a future NASL player and national team captain, liked to play in combat boots. It helped his touch and intimidated others. “Davey would thump people into the fence wearing his brother’s Army boots from Vietnam. They were lethal,” recalled one participant.

Harrison’s D’Errico and Kearny’s Eddie Austin, another future pro, went off to Hartwick College to continue playing, and Hugh wanted to join them. He was crushed when Hartwick couldn’t offer him a full athletic scholarship, so he settled for the University of Bridgeport. He became an All-America selection at the Connecticut school, and upon graduation coaching legend Manfred Schellscheidt drafted him to play for the Hartford Bicentennials of the NASL. Schellscheidt had coached O’Neill for years in the N.J. state team program.

“He always wanted to be Jimmie Johnstone, who was an elusive winger for Celtic,” noted the Hall of Fame coach. “Hughie was very elusive, very agile. He could play winger or forward. He was a tough guy to catch.”

After making 16 appearances and scoring two goals in his first NASL campaign, O’Neill wanted to continue playing in the off-season. He had trained previously at St. Mirren in Paisley with Alex Ferguson, the future Manchester United manager, and now there was talk of a trial in Scotland somewhere.

Santiago Formoso, O’Neill’s neighbor in Kearny and fellow Bicentennial teammate, knocked on his front door to tell him the news: “The club got a trial for you in Scotland.” But he was too scared to tell him with whom.

Rangers Guinea Pig

When Mr. O’Neill heard that it was Rangers and that his son was off to play at Ibrox, he said, “You won’t get into the Ibrox tea-room, never mind the dressing room.” There was still the perception that Rangers followed a no Catholic signing policy. Perhaps an American-born Catholic of Scottish ancestry was their Old Firm guinea pig.

Coming off a full NASL season where he played in hundred-degree heat on oven-roasting artificial turf, O’Neill was fit and sharp for the demands of Scottish soccer, mercifully played on grass and in cooler temperatures. After a successful month-long trial, the Kearny native became the first “admitted Catholic” to sign for Rangers F.C.

“I was the first admitted Catholic to play for Rangers. The others like Laurie Blyth or Don Kitchenbrand were not admitted Catholics; it was always an open question shrouded in mystery whether they were or not,” stated O’Neill. “There was no mystery with me. I was a known, admitted Catholic. That’s why I say I’m the first. I am Catholic, and I signed as a Catholic. That’s why I claim I’m the first bona fide Catholic to sign for Rangers.”

There may have been other factors in his signing, though. “I wasn’t stupid,” he admits. “Rangers were looking for a guinea pig to ease their sectarian tensions. They could now say that they had a Catholic on their books. I didn’t care if I was their guinea pig. I was there to improve.”

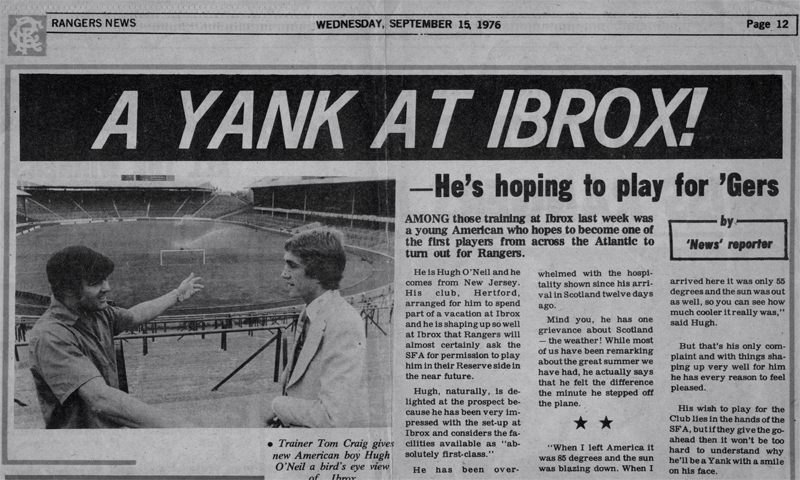

And improve O’Neill did. He trained with a handful of Scottish internationals as well as the other first team and reserve members of the 1976-77 treble winning side. But O’Neill was far from an anonymous Yank looking to better his career. Shortly after signing, the Daily Record pictured him in a Rangers uniform below the headline: “RC’s Son Signs for Rangers.” People knew who he was, and while some supported him, others detested him.

When some Rangers supporters saw him, they yelled: “You Yankee, Fenian, Cowboy Bastard.” Hugh was also involved in a few street scuffles that were never publicized, but after one such incident he turned to a few of his Rangers’ teammates and said, “Am I in this alone?” Hugh’s roommate, a strapping lad from Aberdeen, responded, “If they come for you, they’ll have to come through me first.”

“I wasn’t afraid of New York City in the 1970s, but I was frightened of Glasgow then. It was a very violent time and place,” admitted O’Neill. “Sectarian violence was common. War drums were beating. It was frightening. There were a lot of stabbings. Glasgow wasn’t the city of culture it became in the 1990s, when all the soot from the Industrial Revolution got washed off the buildings. They now have wine bars and little bistros outside. It was more like Dickens, you’d get stabbed in a dark alley.” In 1975, for example, an Old Firm match led to two murders, nine stabbings, and dozens of aggravated assaults.

Amid all the violence and vitriol, O’Neill had to prove himself as a soccer player—a task that was not easy considering so few Americans plied their trade in Europe at the time. And he was an attacking player no less, one who was expected to create chances and score goals. He played in over twenty reserve league matches and cup games during his stay, scoring five goals and assisting on ten others.

O’Neill never broke into the first team (Scottish international Derek Parlane played his position), but he was told he showed promise by first-team manager Jock Wallace. The reserve team won the treble that season, and Hugh contributed to the side’s success except for matches against Celtic.

“I played against every other reserve team in the league but Celtic,” recalled a puzzled O’Neill. “Maybe they thought I would just roll over against them, and I’m sure the Celtic players would’ve wanted to kick the hell out of me.” To this day, Hugh’s Celtic-supporting friends tell others, “That bastard played for Rangers.”

O’Neill’s father was no doubt proud that his son was making the grade in his first full year of professional soccer, but he had to be concerned about his son’s safety in Glasgow. He knew how tense the rivalry was and how serious sectarianism could get, yet it was O’Neill, Jr.’s health, not his son’s, that led to the end of the Rangers experiment.

Mr. O’Neill suffered a massive heart attack—some say the stress of his son’s time at Ibrox caused it—and underwent triple by-pass surgery at a Newark hospital. Hughie was told to stay in Glasgow, but he cancelled his contract and headed back home to Kearny, his ailing father, and a second season in the NASL.

The Bicentennials toured Portugal in the preseason, and Hugh was fit, fast, and full of confidence after his stint at Rangers. He played well against Lisbon giants Benfica and Sporting, and found himself in the starting line-up against Pele’s New York Cosmos at the Yale Bowl. He scored a goal, but found himself on waivers the next week. Such were the vagaries of the NASL for promising young Americans.

(Photo: Personal Collection of Hugh O’Neill)

He spent the rest of the 1977 with the Dallas Tornados before moving to the Memphis Rouges, a new franchise, the following year. There he not only played, but served as the club’s youth director. He even read jingles for radio and television, including the team’s fight song: “We’re the Ramblin’ Rogues from Memphis, the biggest kick in town!”

O’Neill’s professional career ended in another Southern town—Charlotte—with the Carolina Lightning’ of the American Soccer League. He scored the winning goal in the ASL’s championship game in 1981.

Decades on from his stint at Rangers, Hugh O’Neill is an admitted and committed Celtic F.C. supporter. He is an ex-president of the New Jersey Celtic Supporters’ Club and is currently an officer at the Irish American Club. He watches most of Celtic’s matches at The Irish, including the most recent Champions League games. But the last few seasons will be remembered for the absence of the old enemy. Rangers F.C. was demoted to the fourth tier of Scottish soccer in 2012 due to its financial misdoings and eventual bankruptcy. “It was the strangest year in the history of Scottish soccer because it’s the first time that Celtic doesn’t have Rangers,” proclaimed the first admitted Catholic to play for Rangers. “It’s the first time since 1888 that there will be no Old Firm.”

It was a strange year, perhaps as strange as the one when a Catholic, Celtic-supporting kid from Kearny, New Jersey went to play for Rangers.

Aside from football and soccer, there are a lot of sports that you can bet through some esports betting sites which is now available in our present time today.

A version of this article first appeared in XI Quarterly, Volume IV (2012).

I used to live in Scotland and our family doctor’s father, Dr. Willie Kivlichin, father, was the first catholic to play for Rangers. He signed with them in 1905 and played for two years. He moved to Celtic and eventually became team doctor, attending to John Thomson when he died during an old firm match in 1931.

brilliant article, proud to be Shugys friend.

Forget Kitchenbrand etc for a moment, what about Archie Kyle, grand father f the legendary Frankie Miller.

He was one of a number of Roman Catholic players at the club during the early 1900s. Kyle made 110 appearances for the club and scored 52 goals.

The myth over Mo Johnston needs to be debunked once and for all.

thanks

Thanks for watching !

First RC etc starts from the time fod implemented their no RC policy (which was not officially at their inception) and is also split into their so called modern times and their so called good old days Just think of the players they would not sign and we have had they great pleasure of watching