Thanks to Brian D. Bunk, Tom McCabe, Kurt Rausch, Michael Kielty, and Roger Allaway for advice, assistance, and inspiration. Any errors below are my own.

Organized soccer in Massachusetts first developed not in Boston, its largest city, but in the state’s largest mill town, Fall River. Industrial towns like Fall River were magnets for immigrant workers. These workers brought with them from the United Kingdom and Canada association football, better known in the United States as soccer, the sport that over the next century became the most popular in the world. Many of the same industries that drew workers to Fall River were also present in nearby Pawtucket in Rhode Island. The early development of soccer in Fall River and Pawtucket was closely interrelated.

In the ten years after the founding of the Fall River’s East End club in 1883, the Fall River and Pawtucket soccer scenes developed at a rapid pace. Moving from challenge games to organized competitions and leagues administered by local associations, to inter-city matches, participation and dominance in a national championship tournament, and also participation in international play, the two cities saw some of the largest recorded match attendance numbers of the day. Along the way junior club competitions were organized to develop local talent and some of the earliest examples of professionalism in the history of soccer in the United States emerged. These developments were enthusiastically reported by local newspapers with near daily coverage, helping to make the Fall River-Pawtucket soccer axis a leading center of the sport during its early history in the United States.

A combination of local and national factors then led to the collapse of organized soccer in Fall River and Pawtucket over the span of three seasons beginning with the 1894–95 season.

First games and clubs in Fall River

Available records indicate soccer was played in Fall River as early as October 1879, when the Borden Mill Block team defeated the Tenth Street team 3–1 in a “match game of football,” underscoring from this early date the importance of both the workplace and the neighborhood in the early development of soccer in the United States.[1] Newspaper reports are elusive but soccer almost certainly continued to be played after 1879 in the form of informal pickup and one-off games between sides gathered in response to challenges from other workplace- or neighborhood-based teams. The move from ad hoc sides to organized teams gained momentum beginning in 1883 after the founding of the East End Cricket and Football Club, one of a trio of sides that over the next ten years helped to establish Fall River’s reputation as a leading center of soccer in the U.S. By April 1884 the club had some forty members.[2] The connection between cricket and soccer was important. One report in 1885 described “the numerous football clubs in the city, which are mostly made up of cricketers, have, through the winter, materially helped to foster an athletic spirit, and have kept the men in good trim for their work on the crease.”[3]

The first East End game was played on the public holiday of Fast Day on April 16, 1883, when the team defeated the North End Cricket and Football Club. For their victory East End was awarded a silver cup “given by Thomas Walton,” who was “for many years overseer of the weaving department of the Narragansett mill” and later was elected as a city councilman.[4] The East Ends were undefeated as challenge matches continued over the next year against the Old Bedford Road and Flint Juniors teams, as well as a best-out-of-three series against the Globe team. On October 21, 1884, East End hosted its first match against an out-of-state opponent, a 5–1 victory over Providence Wanderers at the Fall River Baseball Grounds. Four days later the team made its first trip outside of Fall River to defeat the New Bedford North End team 9–0. East End played twenty-three matches from October 1884 through May 1885, winning 15, losing four and drawing four, outscoring their opponents by 63 goals to 25.[5]

Organized play begins in Fall River

In November 1884, Fall River’s first organized soccer tournament was announced. Sponsored by local restaurant owner Charles H. Baxter, the tournament included six clubs: Barnaby Mill, Conanicut, County Street Rovers, East End, Globe, and North End. The County Street Rovers soon gained fame as simply the Rovers.[6] Baxter Tournament matchups were decided on a “best two in three games” basis with the tournament winner receiving a silver cup. The second-place team received a “Regulation Foot Ball,” at the time a rare and valuable commodity.[7] The Fall River Daily Herald observed that before the tournament was organized “little interest” was taken in Fall River in soccer but with the announcement of prizes for the tournament winner “new clubs sprang up.”[8] By January 1885, three teams remained in the Baxter Tournament: East End, North End, and Conanicut.[9] Public interest in the matches quickly grew as the championship race tightened and some three thousand spectators were on hand to see the East Ends and Conanicuts meet in March 1885.[10] In April 1885 the Daily Herald declared the tournament a “decided success.” Soccer had now “clearly taken a position among the leading sports in this city, and to see the thousands of people who assembled every Saturday on the park during the winter months to witness the games for the cup presented by Mr. Charles H. Baxter would convince the most skeptical individual that football has become as popular in winter as baseball in summer.”[11] On May 23, 1885, Conanicuts defeated East End 4–1 to claim the Baxter Cup.[12]

Meanwhile, in January 1885, a second tournament was announced. Backed by local tavern owner George Field, the Field Tournament featured seven teams, the six entered the Baxter Tournament plus the Mechanics team, with games to be played out over fifteen match days.[13] Public support for the new tournament echoed that of the Baxter Tournament, with two thousand spectators on hand to see the County Street Rovers face East End in March 1885.[14] In June 1885, North End was declared the tournament winner.[15]

The start of tournament play in Fall River coincided with the beginning of admission being charged for both tournament and exhibition matches. Admission was ten cents in 1885, about $2.90 in today’s value, with “ladies free.” When East End hosted Providence Wanderers in an exhibition match on April 2, 1885, two hundred and fifty people paid to see the game. The Daily Herald reported, “The proceeds, after paying expenses, were $15 [$431], of which the visitors got one-fourth and the Orphans’ home $10 [$287].” The report noted “free games” played on the same day “interfered somewhat with the attendance, as charging admission is a new feature in football matches.”[16] A report two weeks later detailed the expenses involved for a game in which East End defeated the Barnaby Mill club. One hundred and forty-three spectators had paid the 10 cents admission fee for $14.30 in gate receipts, about $411 in today’s value: “Expenses, use of the grounds, $2; Delaney & Keogh, $1.35; advertising in Fall River Herald, four times, $2.75; in DAILY NEWS, four times, $2; total, $8.16. Balance for Orphans’ Home $6.20.”[17] The match was played on the city’s baseball grounds, which had to be rented for the game, underscoring the growing need for clubs to control their own grounds to better manage that expense. Delaney & Keogh was a local printing company, who presumably printed handbills and/or posters to advertise the game. Combining printing costs with the cost of advertising the game in local newspapers, $6.10, or 43 percent, of the receipts went to advertising expenses.[18] By 1894, admission had increased to 15 cents, or about $4.86 today.[19]

The Bristol County Football Association formed

In August 1885, local saloon owner and sports promoter John Gastall announced he was backing a new tournament and offering a silver cup to the winner.[20] A few days after reports of Gastall’s offer, a new organization was announced, the Fall River Football Association (FRFA), which backed another new tournament with matches to be staged at North End’s enclosed grounds. The entrance fee for clubs to join the FRFA was one dollar. Professional players were banned from participating, underscoring that even at this early date the possibility that some players were receiving payment for their services.[21] Whether payment was in the form of inducements to join a club such as a signing bonus, a portion of gate receipts from charging admission to matches—perhaps encompassed by the “paying expenses” as described above—or from the division of the “purse” offered in challenge matches is unknown. Such purses could be substantial. When East End and the Rovers met for a challenge match in June 1886, a purse of $200 was there to play for, the equivalent of nearly $6,000 in today’s value.[22]

The offering of prize purses was not without controversy. In the just mentioned East End-Rovers match for a $200 purse, one East End backer, Joseph Edwards, disputed a goal awarded by the referee, William Emmett, as being offside. The Daily Herald reported,

Mr. Emmett said that his decision had been given and he would not change it. Mr. Edwards then drove down to the stakeholder, Samuel Hyde, and protested against paying the money. He received assurances that the stakes would not be delivered to the Rovers, but when he called at 9:30 the money had been paid. The loser claims that Mr. Emmet was interested in the game and had urged his friends to bet against the East Ends.[23]

Newspapers also reported accusations of thrown matches. When the Olympics defeated the Rovers in a Bristol County Cup match in May 1888, the Fall River Daily Evening News reported “Considerable money changed hands.” One fan who had watched the game observed, “It looked as if the game was thrown for the sake of raking in the innocent next time, or that the Rovers have been wonderfully over estimated.” The report dryly concluded, “Certain it is that interest has been increased in the rivalry between the two clubs and the next game will be an exciting one.”[24]

Stakes were also offered despite the risk to a club’s eligibility to participate in an organized competition. Dissatisfied that the Free Wanderers had been defeated by the Rovers in December 1886, John Denton issued a challenge for a series of games:

I find in regard to my challenge on behalf of the Free Wanderers Football club of Pawtucket to the Rovers of Fall River, that the rules of the Rhode Island association will not allow of playing for stakes under pain of disqualification for the cup contest. The Free Wanderers are ready, however, to play a series of three games with the Rovers, and I will bet $200 to $500 that they will win two out of three games … Upon receiving an answer to the above I will deposit $50 as a forfeit with the [Providence] Telegram, that paper also to be final stakeholder.[25]

In addition to acting as stakeholder for bets, newspapers regularly reported betting odds for sporting events, including for soccer. Describing betting traffic for an American Cup semifinal match in January 1889 between the Free Wanderers and Rovers that was won by the Rovers, one report described,

Betting was very heavy, the Rovers being liberally backed. At the opening of the game $25 and $20 were the odds given in favor of the Rovers, and as the game progressed $2 to $1 and $3 to $1 were offered, with no takers. It is estimated that the friends of the Rovers won $5,000.[26]

In today’s value, the friends of the Rovers thus came away with the equivalent of more than $155,500. “Local sporting men” in Fall River offered odds for the 1888–89 American Cup final between the Newark Caledonians and Rovers at “eight to five in favor of the Rovers” the day of the match: “A few offers were taken last night, but most of the money went begging.”[27]

The formation of the FRFA represented a step toward the creation of a formal administrative body to govern soccer in Fall River and a step away from one-off tournaments sponsored by local businessmen like Baxter, Field and Gastall. Unsurprisingly, friction could result. A report in October 1885 said Gastall, who likely expected to profit from gate receipts and managing bets on games, believed he was being treated unfairly by the FRFA and was now offering a fifty-dollar cash prize to the winner of his tournament.[28] No further reports have been found to confirm whether the Gastall tournament was completed or even staged.

The FRFA originally limited membership to clubs within Fall River. In October the association announced a new name, the Bristol County Football Association (BCFA), opening membership to clubs outside of the city. Among the clubs joining the new association were Fall River Olympics. The Olympics, along with East End and Rovers, formed the trio of teams that established Fall River’s reputation in the first two decades of organized soccer competition in the U.S. In addition to the Olympics, five other Fall River teams were included in the tournament schedule: Conanicuts, East End, North End, Rangers, and Rovers, along with New Bedford North End.[29] The first Bristol County Cup match was played on October 24, 1885, with the Rovers defeating New Bedford 2–1. The Rovers dominated the county championship, winning the title in 1885–86, 1886–87, 1888–89, 1889–90, and 1890–91. The Olympics won the 1887–88 and 1891–92 editions before East End won the 1892–93 series, after which the Bristol County Cup was awarded to the winner of a new junior soccer league.[30]

Despite the formation of the BCFA, local promoters continued to back challenge matches outside of the association’s administration. In April 1886, a “best three out of five” series of games was announced between East End and Rovers for “$25 a side and Marsh’s silver Cup.” Backed by John Marsh, “proprietor of Star Music hall,” the trophy was “for the champion football team of the city.”[31] The series went to five games with over two thousand spectators on hand to see the decisive match at the County Street Grounds on May 22, 1886. But when the East Ends took to the field the Rovers objected to the presence of one player, who was “said to be a professional.” The East Ends refused to play without him, so the Rovers left the field, giving the East Ends the city championship.[32]

“Quite a crowd gathered” when the Marsh Cup was presented to East End two days after the disputed game, and “Stones, apples and other articles were hurled through the air” by rival supporters. No injuries were reported but police “were unable to disperse the crowd” and “the revelry” continued until after midnight.[33] Violence involving supporters was not uncommon. A report in January 1887 described a fight on a streetcar between “a number of men” on their way to see a match at the North End Grounds in which one man was “cut with a jack-knife.”[34]

Soccer in the late nineteenth century was a much rougher game than it is today and reports of flaring tempers leading to an exchange of blows between players are not uncommon. On-field fights between players could also lead to pitch invasions by fans. When a “hot fight” between two players began during an American Cup tie between the Olympics and Rovers in October 1891, the Fall River Daily Globe reported, “The crowd rushed in upon the field and the police with difficulty separated the fighters. Matters were in such a hubbub that Referee Cook declared the game a draw as it was impossible to clear the field.”[35] A week later, repeated violent play and fans rushing onto the field resulted in the referee ending the American Cup match between East End and the Free Wanderers before full time.[36] Violence between rival players off the field also occurred. In June 1886 after the conclusion of the Marsh Cup series, four members of the Rovers were charged with assaulting the East End goalkeeper, but the charges were dismissed.[37]

Developments in Rhode Island

Soccer was played in Rhode Island at least as early as 1884 as evidenced by the Providence team that faced Fall River East End in October of that year.[38] But the sport was almost certainly played in the Ocean State before that game. When the ONT Athletic Association of Newark, New Jersey played a match between single and married members on December 1, 1883, two umpires “came on from Pawtucket, R. I. purposely” to officiate the match. Providence sent a representative to the founding meeting of the American Football Association in New York City on May 24, 1884. A Providence team also participated in a four-a-side tournament six days later in Manhattan that included other founding AFA clubs.[39] As was the case in Fall River, early matches in Rhode Island were likely pickup or one-off challenge games that didn’t catch the attention of local newspapers.

What would become the leading Rhode Island team of the day, the Pawtucket Free Wanderers, organized in 1885. Organized league play began in fall 1886 with the formation of the Rhode Island Football Association (RIFA), which included the Free Wanderers and teams from Ashton, Lorraine, Providence, River Point, and Thornton. Like the Barnaby Mill team in Fall River, some RIFA clubs were backed by area manufacturers, underscoring links in soccer’s development on the East coast during this period to the workplace, particularly the textile industry, and immigrant workers.[40] The Free Wanderers, for example, had connections to the Conant Thread Company, the U.S. subsidiary of Scottish-based J & P Coats, the Thornton team to the British Hosiery Company, whose “workforce came from Nottingham, England.”[41]

The first match in Pawtucket “for the association cup” was played on November 20, 1886, with the Free Wanderers, the eventual inaugural champion, defeating the River Point team, 14–0.[42] As was the case in Bristol County, challenge matches outside of the governance of the Rhode Island Football Association continued—whether by association sides looking to fill open dates on the calendar or by unaffiliated teams testing themselves against more established sides. Nevertheless, membership in the association provided benefits such as a published calendar of matches with an agreed upon process for rescheduling postponed games, the assignment of referees, and an adjudicating body to decide disputes between clubs. All of this helped grow interest in—and encouraged newspaper coverage of—soccer by ensuring an accepted path to a recognized championship with medals and a championship trophy for players and clubs to play for.

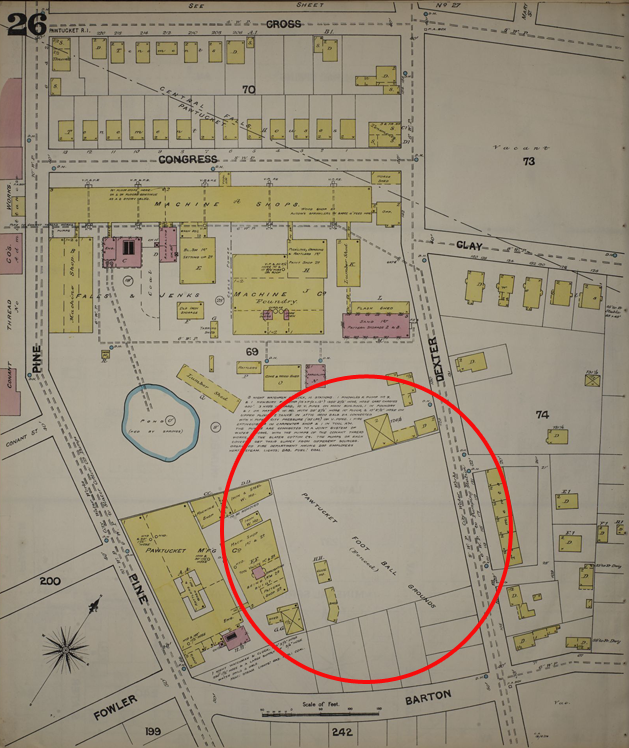

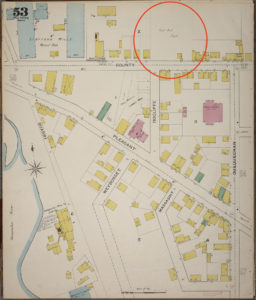

One problem every team faced was having their own grounds for matches. In March 1887, the Free Wanderers secured the location of the Dexter Street Grounds— “the lot of land at the corner of Barton and Dexter Streets, 140×80 yards”—which became one of the legendary grounds of early American soccer history.[43] The team quickly worked to enclose the field, which meant it was able to control access to games in order to charge admission. Improvements to the grounds’ facilities followed, including construction of a new clubhouse, as well as a dressing room and bathroom for players, in 1889. A covered grandstand capable of seating more than one thousand spectators was constructed in 1890.[44] Club revenue wasn’t restricted to soccer games, with the grounds leased in the off-season for baseball and the occasional visiting circus.[45]

In May 1888, the Free Wanderers withdrew from RIFA after a protest by the Thorntons resulted in the association ordering the replay of a match the Pawtucket team had won. One report noted, “The Wanderers are the strongest team in the Rhode Island Association and have won so many victories that their patronage has fallen off, as the games have been too one sided. When a team from out of the State visits here there is always a good attendance.”[46] The Free Wanderers simply outclassed their in-state opponents. Nevertheless, the team rejoined RIFA the following season and defeated the Thorntons to reclaim the state championship, winning it again in 1890.[47] But it was clear that the path to greater success led across the state border.

The proximity of Fall River to the cluster of Rhode Island mill towns just across the state border made for easy communication and travel between the burgeoning soccer centers. The Providence Wanderers were the first side to make the journey to the Spindle City in October 1884 to face East End, visiting again in February 1885 to face the Barnaby Mill team, losing 5–0. A return game in Providence on March 28 saw the Wanderers win 2–1 after the Barnabys left the field following a disputed goal. The Providence team was then defeated by East Ends in Fall River on April 2.[48] The Pawtucket Free Wanderers traveled to Fall River for the first time in May 1886 to face an all-Fall River team, losing 2–3. In October 1886, the Rovers defeated the Thorntons 3–2 in Providence. Cross-border contests featuring the Free Wanderers against Fall River sides continued in spring 1887.[49] In November 1887, matches between picked sides representing the Rhode Island and the Bristol County association commenced.[50]

Onto the national stage

As the Free Wanderers in Pawtucket, and East End, Olympics, and Rovers in Fall River, established themselves as regional powers, their aspirations turned toward success in the American Football Association’s American Cup tournament. First organized by the AFA in 1884, the American Cup tournament was touted as the championship of the United States. But the first three editions of the competition, each won by the ONT team of Newark, New Jersey, only featured sides from New Jersey and New York City.

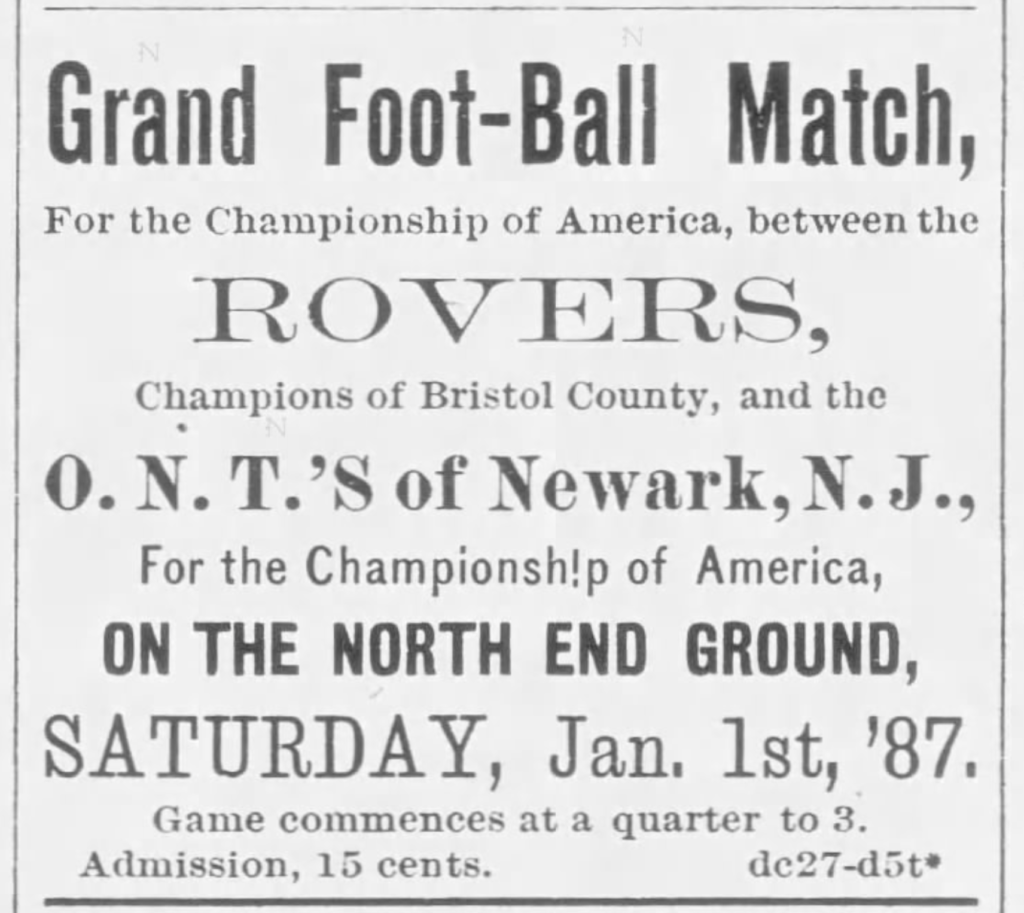

On New Year’s Day 1887, ONT visited Fall River for an exhibition match, defeating the Rovers 2–0 at the North End Grounds in front of fifteen hundred people in a match advertised as “For the Championship of America.” With the visitors were two former Fall River players who had left the city to join ONT in 1885, Joseph Swarbrick, formerly of the East Ends, and Harry Holden, formerly of the North Ends, two early examples of the kind of player movement that would become more common over the coming years.[51] Player movement went both ways. Frank Cornell, center forward for the 1888-89 American Cup champion Rovers team, had played for Newark Almas against the Rovers when the Fall River side won the 1887–88 final.[52] It also occurred among teams in the same league for important competitions. When East End and the Conanicuts met in the American Cup for a semifinal match in March 1892, they were the only teams remaining from Massachusetts or Rhode Island in the tournament so both sides borrowed players from already eliminated clubs. East End’s lineup for the day included two players from the Free Wanderers while the Conanicuts roster included players from the Rovers, Olympics, and Free Wanderers.[53]

The New Year’s Day 1887 match against ONT was the beginning of a series of exhibition games featuring Fall River and Pawtucket sides against teams from New Jersey. On January 29, the Rovers defeated Kearny Rangers 2–1 at the North End Grounds.[54] The Rovers traveled to play ONT in a return match on February 22, 1887, defeating the American Cup holders 3–2, the team’s first-ever loss at its home grounds. When news of the Rovers victory reached Fall River that night, bonfires were lit in celebration and “a high old time was indulged in until a late hour.” Accusations that the Rovers had been ill-treated by ONT after the game were later vigorously denied.[55]

The Rovers and East End entered the American Cup tournament in September 1887, joined by fellow New England sides Pawtucket Free Wanderers, Providence, and the Ansonia team of Connecticut. Ten teams from New Jersey and New York also entered the tournament.[56] In the interest of minimizing travel expenses, fixtures were arranged regionally, the New England sides forming the Eastern District, the New Jersey and New York clubs forming the Western District. Eastern District games commenced on October 29, 1887, the Rovers defeating East End 3–1 and Providence falling 1–4 at home to the Free Wanderers.

Exhibition inter-city matches continued while play in the American Cup tournament progressed. When ONT returned to Fall River for an exhibition match on November 24, Thanksgiving Day, they faced East End, decisively winning 4–0.[57] The Rovers eliminated the Free Wanderers from the American Cup tournament with a 3–0 win on December 3. On Christmas Eve, the Almas traveled to Pawtucket for the first of three exhibition matches and were defeated 2–1 by the Free Wanderers. On December 26 in Fall River, the Almas lost 3-0 to the Rovers in the morning before falling 3–2 to the Olympics in the afternoon.[58]

The Rovers hosted Kearny Rangers in the American Cup semifinal on March 3, 1888, earning a decisive 6–1 victory. The Rovers nearly matched that scoreline in the tournament final at the ONT Grounds in Newark on April 14 when they defeated the Almas 5–1 to claim the championship. The Rovers victory marked the beginning of the Eastern District’s dominance of the tournament. The Rovers repeated as champions in 1888–89. Fall River Olympics won the 1889–90 tournament. East End were back-to-back champions in 1890–91 and 1891–92. Pawtucket Free Wanderers claimed the 1892–93 championship before the Olympics won again in 1893–94.

So strong was the Eastern District’s dominance that local semifinal winners, which were determined by matchups between teams from the same district beginning with the 1889–90 tournament, were soon referred to in local press reports as the de facto winner of the tournament before the final was even played: it was simply assumed the Eastern District semifinal winner would dispatch whichever unfortunate New Jersey or New York club faced them in the final. For example, one report in December 1889 said of the upcoming semifinal between the Olympics and Free Wanders, “That this game will be the deciding game of the holding of the American cup for the coming year is very certain. It has been plainly shown that the eastern teams are much superior to the other teams composing the American association.”[59] And, for a time, such an assertion was undeniably true.

American Cup games could draw significant crowds. Some five thousand spectators were on hand at the Dexter Street Grounds to see the Free Wanderers battle the Rovers in the semifinal in January 1889, with one report describing the attendance as “the largest ever seen at an out-door game in this city.” Six hundred Rovers supporters traveled from Fall River to see the game. Demand at the gate was so great that a “dense crowd” was still outside the grounds when play commenced because tickets couldn’t be sold fast enough. Despite the presence “of a strong force of policemen,” after the first goal was scored “several hundred” fans broke through the gates without tickets. To put the attendance number in perspective, Pawtucket’s population in the 1890 Census was 27,633.[60]

At an American Cup tie in October 1889, “Over 4000 spectators,” including four hundred who traveled from Pawtucket, saw the Rovers defeat the Free Wanderers 4–1. The Daily Globe reported the attendance “was the largest ever recorded at any athletic event in this city.”[61] When East End hosted the Rovers in February 1891, “close on 5000” spectators surrounded the field. Reported attendance for the American Cup semifinal between East End and Conanicuts in March 1892 was “about 6000.”[62] Fall River’s population in the 1890 Census was 74,398.[63] Such large attendance numbers did not go unrecognized by the AFA and in 1890, the Dexter Street Grounds became the first outside of northern New Jersey to host an American Cup final, hosting the championship game again in 1891. Fall River’s County Street Grounds was the site of the 1892–93 final before the 1893–94 final was staged at the Rovers Grounds.[64]

Large attendance numbers meant large gate receipts, of which the AFA took a fifteen percent cut, the association’s principal means of funding. In Fall River, this fueled resentment toward the AFA, which was increasingly viewed as beholden to soccer interests in northern New Jersey and New York City, where attendance lagged far behind the numbers seen in Eastern District games. A report in May 1893 noted,

Monies received from all the American Cup games played in New York and New Jersey have not amounted to over $30, while two of the games played in Fall River reached nearly $260. The entire gate receipts of the Rover and Pawtucket games were $713 and in the Rover and Olympic Games $466. The association got 15 percent of this, or almost $200. After the purchassing [sic] of medals and other incidentals, such as suppers and sundries, it is expected that there will be little or nothing left to add to the $750 already in the association treasury.[65]

The financial breakdown makes clear the widely held view in Fall River that the AFA depended on funds derived from Eastern District matches. A letter to the Daily Globe in October 1889 argued, the “function” of Western District teams in New Jersey and New York “seems to be to dictate to the rest of the Association and receive gate receipts from the eastern clubs.”[66] As displeasure with the AFA grew in Fall River it was also suggested that the Free Wanderers “have ‘a pull’ with the football drones of New Jersey.” Questions were raised about how the association handled its funds and calls were made to shift AFA headquarters from Newark to Fall River for more effective oversight of association finances.[67]

Success in the American Cup tournament helped grow the reputations of the Fall River and Pawtucket soccer scenes. That, along with the presence of enclosed grounds facilitating the charging of admission to the consistently large number of soccer fans willing to pay to see matches, made the cities desirable destinations first for exhibition games against visiting clubs and later for American Cup finals. As well as growing clubs’ reputations, exhibition matches could be a lucrative means to grow clubs’ coffers. Between 1887 and 1891 Fall River and Pawtucket clubs hosted more than fifty exhibition games against visiting club and all-association teams. Aside from facing one another, the leading Fall River and Pawtucket clubs rarely traveled for exhibition games. Why incur travel expenses to play an exhibition match in places where soccer wasn’t as well supported when more money was more certain to be made by hosting matches?

International play

The growing reputation of Fall River and Pawtucket in the American soccer scene soon translated into international play. After the Canadian side representing Ontario’s Western Football Association (WFA) defeated an All-AFA side 5–0 in Newark on Thanksgiving Day 1887, an All-New England side made up of players selected from AFA teams in Fall River, Pawtucket, and Providence played the visitors to a scoreless draw in Fall River on November 26.[68] Five players from the Rovers were selected for the AFA team that played three matches in Canada in May 1888, returning with one win and two draws.[69] In May 1889, the Rovers embarked on their own three-game tour in Canada, winning one game and losing two.[70] A representative WFA side returned in 1890 for another Thanksgiving visit, losing 3–1 on November 27 to the Rovers. Attendance was reported at four thousand spectators, “the largest ever seen at the grounds.” Two days later in Pawtucket the Free Wanderers defeated the Canadian side 2–0.[71]

Reports of possible transatlantic matches began in summer 1890 with talk of a visit by the Clyde team of Scotland to face the Rovers but the visit, met with considerable skepticism in more realistic circles, never materialized.[72] The following spring in April 1891 Fall River newspaper reports detailed plans for a picked team to be organized to tour England. News of the tour plans was reported as far away as Chicago. An offer from ex-city councilman Alfred Hanson to put up $1,000 to back the tour was soon matched by local confectioner David Howarth with Daily Evening News reporter John Crowther to act as a consultant in selecting fifteen players “to make this a representative American team.”[73] Administrators for the “International Football Club of America” were announced – “nothing now remains to be done but complete the details of the arrangement”—and applications to join the team reportedly came from as far away as Philadelphia.[74] But the effort to organize an American team came to nothing. Nevertheless, Fall River and Pawtucket players soon would make the trip across the Atlantic as part of another touring team.

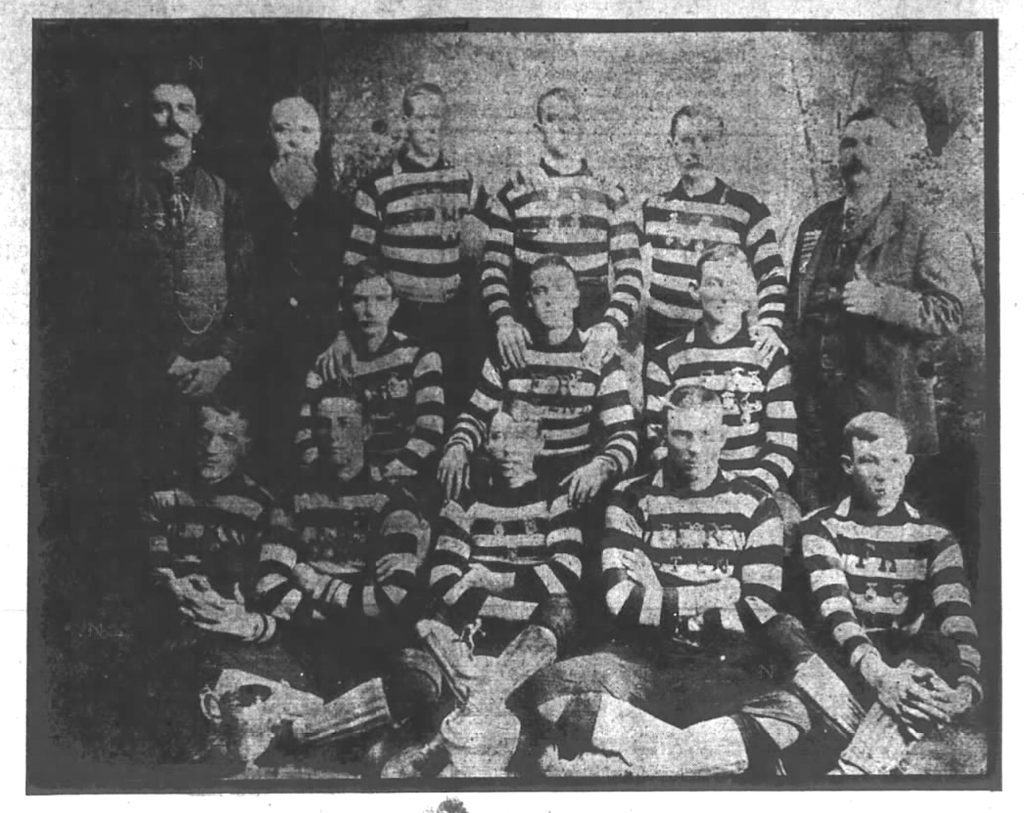

(Front Row) Dennis Shea (Rovers), Alex Jeffery (Free Wanderers), Bowman, Senkler, Neil Munro (Free Wanderers); (Middle Row) Warbrick, Henry Waring (Rovers), Thibodo; (Back Row) James Whittaker (Olympics), Gregory, Joseph Buckley (Rovers). Image courtesy of Michael Kielty.

In June 1891, a team representing the New England League made up of players from Fall River and Pawtucket played four games in Canada, winning three and drawing one.[75] The New England team impressed observers in Canada. When promoters of a team representing Canada scheduled to tour the United Kingdom in 1891 were unable to secure enough Canadian players to fill the roster, nine Eastern District players joined the touring team, five from the Rovers, three from the Free Wanderers, and one from the Olympics. Playing a grueling schedule in Ireland, Scotland, and England of fifty-eight matches over twenty weeks between the end of August 1891 and the second week of January 1892, the Canadian American team returned home with a record of 13 wins, 14 draws and 31 defeats.[76]

The Toronto Varsity team visited Pawtucket on May 30, 1893, the first visit by a Canadian club team, losing 5–2 to the Free Wanderers in front of four thousand spectators at the Dexter Street Grounds before defeating their hosts the next day 3–2 in a night game played under electric lights in front of ten thousand spectators, likely the largest attendance ever reported for a soccer game in the United States at that time. On June 3, the Toronto side drew 3–3 with East End in Fall River.[77]

New England League formed

In February 1889 an inter-city challenge series called the Citizens’ Cup featuring the Free Wanderers against the Rovers began that was ultimately won by the Rovers.[78] The series ended in controversy when in the final match the Rovers, who had already clinched the cup, left the field after conceding two early goals. In response, the Free Wanderers management refused to hand over the visitors’ share of the gate receipts. Acrimony between the two sides continued when the Rovers defeated the Free Wanderers in the first round of the 1889–90 American Cup and then refused to give the Pawtucket side their cut of the gate receipts. The Free Wanderers protested to the AFA, who ordered the match replayed. Instead, the Rovers, reigning American Cup champions, withdrew from the tournament.[79]

Withdrawing from the American Cup appears not to have grievously affected the financial health of the Rovers. At a meeting in July 1890, the treasurer’s report showed a balance of $975.72, the equivalent of about $29,894 in today’s value. $280, or about $8,579, was authorized to pay for the construction of a grandstand on the club’s grounds. A discussion followed about an offer for the club to purchase the land on which its grounds were situated. The asking price was fifteen dollars per rod—the grounds consisted of “426 rods” with a rod equal to five-and-a-half yards—or $6,390, about $195,774 today. This was too much for the club to bear: “If the money were borrowed, the interest would be $350 a year, and the ordinary net earnings of the club, in a season, would hardly be sufficient to meet this account.”[80] In addition to concerns about interest charges, another report underscored the club’s need to meet the costs of paying for players, highlighting again the presence of professionalism at this time: “The players too are crying out for more money so that the buying of the grounds will not take place this year.”[81]

After the Rovers withdrew from the American Cup the club led efforts to form what was to be called the New England Football League. Reports described interest in the proposed league from ten clubs including the Rovers, East End, Olympics, Chase Street Rovers and Athletics in Fall River, fellow Massachusetts sides in Lawrence and Lowell, and the Providence Athletics, Thornton and River Point teams in Rhode Island. Conspicuously absent was the Free Wanderers. In the event, plans for the new league came to naught.[82]

Despite the conflict between the Rovers and Free Wanderers, both were founding members of a newly proposed New England Football League announced in January 1891 with the Free Wanderers’ John W. Clark elected president of the new league. Initial membership in the league, which debuted with a short season running from January through May, was restricted to four teams, with East End and Olympics joining the Rovers and Free Wanderers.[83] Reports acknowledged “money is the main object of the new league,” further underscoring the growing presence of professionalism in Fall River and Pawtucket soccer. Only well-known teams with their own grounds and a reputation for “hard playing” would be admitted. In May 1891, the Free Wanderers defeated the Rovers 1–0 in front of more than three thousand spectators to claim the inaugural New England League championship.[84] Echoing the conceit that the result of the American Cup semifinal in the Eastern District essentially decided the tournament champion, the Free Wanderers distributed handbills promoting the league final that concluded, “This game will settle which is the real champion team of America.”[85]

The next season the league expanded to seven teams with additions from Providence, Fall River, and New Bedford.[86] East End bested the Free Wanderers to win the 1891–92 championship two weeks after defeating New York Thistle for the American Cup title. The Free Wanderers reclaimed New England League supremacy the next season three weeks before they defeated New York Thistle to win the American Cup. The Rovers were awarded the 1893–94 league championship after three Pawtucket teams, the Free Wanderers, North End, and YMCA, withdrew from the league to focus their efforts on the Mayor’s Cup, Pawtucket’s new city championship.[87]

The New England League winner was awarded a pennant for the first two seasons before the Providence Telegram also offered a trophy, first awarded to East End for winning the 1891–92 championship and then the Free Wanderers when they won the 1892–93 season.[88] When the Rovers won the 1893–94 season, the team dispatched a “polite note” requesting the trophy be handed over, but the Free Wanderers refused to do so, arguing the donor first needed to give them permission for the transfer. A month later, the trophy was finally delivered to the Rovers.[89] Harsh winter weather resulting in the repeated postponement of matches led the New England League to call off the 1894–95 season in May 1895, with the Olympics awarded the abandoned season’s championship.[90]

Uninitiated in Boston

If the New England League’s name was justified by the inter-state competition it administered, the absence of Boston or other Massachusetts teams was nevertheless obvious. A Daily Globe report in July 1889 discussed the possibility of organizing a Massachusetts state league but questioned whether “it would pay the local clubs to enter it.” The report observed that if twenty towns in New England existed “where football were [sic] understood and patronized as it is in this city and Pawtucket, the clubs could afford to pay salaries to their players which would enable them to give all their time and energy to the development of the game.”[91] While several mill towns are mentioned in the report, Boston, the largest city in Massachusetts, is not.

In Boston, football generally meant gridiron football, the collegiate game inspired by Rugby as practiced at Harvard University. Reports in Boston newspapers in January 1888 of the founding of the Boston Rovers describing soccer as “something new and unheard of” were read with “Considerable amusement” in Fall River. The Daily Herald observed that since the founding of the East Ends in 1883, soccer in Fall River “rivalled baseball in popularity” and had been followed by the formation of clubs in Rhode Island and New Jersey.[92] If soccer was well known in Fall River it truly was “something new and unheard of” in Boston. Spectators at a Boston Rovers practice game soon after the club’s founding were described by the Boston Herald as “uninitiated in the mysteries of football as played under association rules,” unsurprising given the dominance of gridiron football in the city.[93]

In March 1888, East End traveled to Boston to face the Rovers in the “first game of football played thereabouts under association rules for some years,” shockingly losing 2–1. One Fall River paper brushed off the loss, reporting the Boston team “employed Rugby tactics.” Yet when the Boston team visited Fall River two weeks later, they again defeated the East Ends.[94] Reports soon detailed other teams in mill towns outside of Boston, including the Woburn Rangers, Lowell Rovers, Lawrence Athletic, Newton Mills, and the American Watch Tool Company team in Waltham, with some teams traveling as far as Fall River and Pawtucket for matches, while also hosting the Free Wanderers and the Providence team. By 1889, Springfield United and Holyoke Scotia were playing in central Massachusetts.[95]

Without a league to organize games, Boston-area teams played challenge matches with scarce newspaper coverage. This changed in March 1892 when the Massachusetts Central Association Football League was founded with nine teams: Boston Rovers, East Boston, Chelsea, Malden, Lynn, Quincy, Clinton, and two in Lawrence, the Boston Rovers winning the inaugural championship.[96] But newspaper coverage, and presumably interest in soccer, in Boston remained scant. Elsewhere in Massachusetts, the Worcester County Football League was founded with six clubs in October 1893: Fitchburg Light Blues, North Grafton, Worcester Rovers, Whitinsville, Holyoke Machine Company, and Clinton.[97] In May 1894, the undefeated Fitchburg team hosted Boston Rovers, defeating them, 8–2, to claim the Massachusetts state championship, although no records have been found of Fitchburg playing a Fall River side, and the Worcester County Football League soon withered away.[98] In Boston, soccer remained mysterious to the uninitiated among the sporting public, who by this time could also follow reports on the growing interest in Gaelic football.[99] When the Boston Rovers and Malden team played a shortened exhibition game of “professional football” following a baseball doubleheader between the Boston Beaneaters and Chicago Colts in September 1894, “few spectators” stayed to watch and those who did “laughed long and loudly” at the unfamiliar style of play.[100]

Organized junior and “second class” soccer in Fall River

As described above, one of East End’s earliest opponents was the Flint Juniors team in 1884. In Rhode Island, newspaper reports of matches involving junior teams begin in 1886.[101] Junior clubs and reserve sides were an important way to identify and develop new local talent for senior clubs and, whether explicitly intended or not, the native-born players that would be necessary for the long-term development of soccer in the U.S. sporting landscape. At the start of the 1887–88 season the Bristol County Second Class Football Association was organized for junior sides “so as to bring out young talent.”[102] In January 1888, the Rovers, who were a leading force in organizing the new junior association, donated “an elegant silver water pitcher” to be given as the prize for a competition “between the second class football teams of the city.”[103] The inaugural Second Class Football Association champion was the Clippers. Shortly after the Wamsuttas dethroned the Clippers in June 1889, the Clippers announced the championship cup had been “stolen from their club room.” The Clippers regained the championship in April 1890 before the Wamsuttas reclaimed the title in June 1891.[104] A new cup was awarded to the winner of the 1891–1892 season, with the name of the Rovers Reserves joining the Clippers and Wamsuttas on the list of champions.[105]

In October 1893, the New England League announced a new junior league featuring six teams: the Chace Street Rovers, Eagles, East End Juniors, Rover Juniors, and Swifts from Fall River, plus the Free Wanderers Juniors from Pawtucket. The season champion would be awarded the Bristol County Cup after it was decided to end the senior tournament that had begun in 1885.[106]

While well intentioned, the new junior competition suffered from the New England League prioritizing the scheduling of senior league games on the limited number of grounds available, which was compounded by the need to reschedule postponed senior and junior games as the available matchdays dwindled with the progression of the season. Another problem was a Junior League rule prohibiting a player who had been called up by a senior team from continuing to play in junior competition.[107] By April 1894, the Eagles and East End Juniors had withdrawn from the league leaving the Free Wanderers Juniors, Chace Street Rovers, and the Rovers Juniors level on points and ahead of the Swifts. The Wanderers drew with the Swifts in the beginning of April, but it is unclear if they were awarded the inaugural Junior League Championship. Nevertheless, player development was successfully achieved. The next season, the senior Olympics squad was “made up mostly of last year’s Wanderers, then a junior league club.”[108]

A parish-based league was formed by Fall River’s Holy Names Society for the 1894–95 season. Only members of a given parish could play for that parish team. Consisting of six clubs and called the Catholic Football Association (CFA), it was also announced “that all persons who have played with first class clubs or so-called professional clubs this year be prohibited from playing in the league.”[109] While a report in November 1894 said the CFA was “proving a success,” a report in December noted efforts underway to “assist in the formation of a new league.”[110] It is unclear if the CFA finished the season.

Mayors’ Cups in Fall River and Pawtucket

Five years after the Marsh Cup, Fall River Mayor John W. Coughlin announced in December 1891 a new competition to be called the Mayor’s Cup. Initially featuring East End, Olympics, and Rovers, the new competition would determine the champion of the city, who would receive a silver cup, “valued at $100.” Twenty-five percent of the gate receipts from Mayor’s Cup matches were to be donated to a local charity.[111] After a late start due to poor weather, the cup series continued until July when play was suspended with all three clubs tied on points. Aside from it being too hot to play, the attention of sports fans was now firmly on baseball and cricket. In August 1892 the Mayor’s Cup organizing committee distributed the tournament profits among three local charities—St. Vincent’s Orphan Home, the Notre Dame Orphanage, and the Good Samaritan Hospital—with each receiving $65, the equivalent of about $2,000 today.[112] The 1892–93 edition ended with the organizing committee deciding that East End and the Olympics would share the championship, with each club holding the championship trophy for six months over the next year, and $80 [$2,478] was donated to the St. Vincent’s Orphan Home.[113] Rovers won the 1893–94 Mayor’s Cup but concerns were voiced in the press about how the bad management of funds from matches left little for local charities: “It is said a square meal for hungry delegates used up the charity money.”[114]

In March 1894, Pawtucket Mayor Henry E. Tiepke inaugurated that city’s Mayor’s Cup, with the Free Wanderers, North End, and YMCA teams competing for the city championship. Pawtucket YMCA was awarded the trophy in June after also winning the season’s Rhode Island Football Association title.[115] The YMCA roster later featured Oliver and Fred Watson, two Pawtucket-born brothers who were the first African American players in the US. Between them they were the first African Americans to play in, and score in, a senior league match; the first to play in, and score in, a tournament representing a national championship in the form of the American Cup, the first to win a senior league championship, and the first to play for a professional club.[116]

Professionalism in Fall River and Pawtucket soccer

As we have seen above, professional players were likely present in Fall River as early as 1885. The presence of professional players in team sports was not unfamiliar in Fall River, where cricket teams featured a declared professional player as early as 1884. News of professional baseball games elsewhere around the country was regularly reported and efforts were underway to organize a professional baseball team in Fall River by 1886.[117] Immigrant soccer players and fans from Britain also would have been familiar with the practice of paying players even before England’s Football Association legalized the practice in 1885. Explicit reference to professional soccer players in Fall River and Pawtucket is rare before the 1890s. But as the number of championships to be competed for grew, competition for top players also increased, and there was money to be distributed from gate receipts and the purses offered for challenge matches to acquire players. If prize purses and gate receipts had previously been informally distributed to players, a report in July 1889 suggested the practice would soon become formalized: “It is probable that a new feature will be introduced by one or more of the local clubs this season in the way of giving the players a percentage of the gate receipts.”[118]

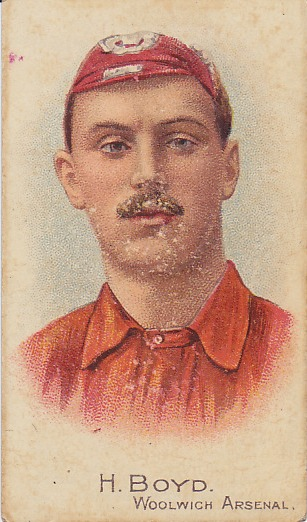

The example of Scottish-born Henry “Harry” Boyd illustrates the use of professional players by leading clubs.[119] Boyd visited Fall River as part of the Chicago Thistles team in September 1891. By December, the Fall River Evening News reported Boyd’s imminent arrival to join the Olympics, noting the Fall River team had “forwarded his fare.”[120] Subsequent reports indicated Boyd had signed with the Olympics to compete in the Bristol County Cup tournament. The Olympics were winners of the 1889–90 American Cup, but the team now was “not strong financially” and probably couldn’t afford to pay Boyd to play for them in all competitions.[121] Soon, it was reported Boyd had turned down an overture from the Rovers, accepting instead “a big offer” from East End to feature for them in the American Cup tournament. Boyd received a tidy sum to sign with the East Ends, “the consideration being variously estimated at from $30 to $50,” or $887 to $1,479 in today’s value.[122] This signing bonus would have been in addition to whatever fee (and travel expenses) he received from the Olympics. For the sake of comparison, Boyd received “a £5 signing on fee” when he joined West Bromwich Albion in October 1892, the equivalent to about £677 in today’s value, or about $914.[123] Thus, the signing bonus East End paid Boyd equaled or exceeded what he later received in England. But a player could also ask for too much. The Free Wanderers wanted to use Boyd for an exhibition match in February 1892 then decided against playing the Scotsman because “his terms were so high.”[124]

Competition between leading clubs in Fall River and Pawtucket for quality talent was strong and a variety of means were employed to compensate players. One New Bedford player explained,

Whenever a player arrives here and shows any sign of ability the Fall River clubs will offer him such inducements as will make him go to the border city…In Fall River when it is learned that a player is to come to this country from England, the club managers get him a good job in some mill and thus secure him permanently. Then again the players there get regular pay for training, and a portion of the gate receipts. The clubs there are well backed with money and can do whatever they please to prosper the game.[125]

Enjoying comparatively strong financial backing, New England League clubs actively searched for new players, both domestically and internationally. Describing the imminent arrival in Boston of two “expert football players” recently arrived from England, one report noted, “their services have been secured by the Free Wanderers.”[126] In addition to paying travel expenses and offering signing bonuses as in the case of Boyd, desirable players might be offered a secure job (one that necessarily offered the flexibility to allow a player time off when needed for soccer-related activities), paid training, and a portion of match receipts. A cut of the gate could be a valuable source of income. For example, attendance at a Christmas Eve 1891 match between the Olympics and East Ends was reportedly between two- and three-thousand spectators.[127] Multiplying the low number with admission costing 15 cents results in a gate of $300, or approximately $9,191 in today’s value. Even after accounting for expenses what remained to be divided among the players was not insignificant. In a city where the average yearly earnings in 1890 was $329.74, or about $6.34 a week, it is reasonable to conclude a player could receive the equivalent of several weeks’ wages for playing ninety minutes of soccer.[128]

At the end of the 1891–92 season, Boyd received “$25 to sign with the Rovers,” the equivalent of about $766 today, before skipping town to return to play in England.[129] Boyd’s signing with the Rovers came amongst a signing frenzy by Fall River’s leading clubs that some viewed with alarm and newspaper reports lamented the creeping effects of professionalism on the game. With signing bonuses “as high as $100 down and $15 per week”—about $3,064 and $460 respectively in today’s dollars, well above the average worker’s wage in Fall River—it was feared quality players would be concentrated in one or two teams who not only could afford to pay players but might also go so far as to sign players and not play them every week to prevent them from playing with competitors.[130] Whatever the ability of leading clubs like East End and Rovers to fulfill the terms of the contracts they offered, competitive balance was viewed as threatened and it was asserted fans would lose interest in following teams that did not have the resources to secure top players and effectively contend for championships. One report observed, “the limits of the game in this country are altogether too narrow to admit of hiring players,” adding, “There are too few good men who are worth a stipend to equip more than two elevens in this city.” Only if “a method of distributing players is adopted as prevails in the baseball leagues” could the dangers of professionalism be avoided.[131]

The intensity of signing activity and the amounts offered for signing bonuses fluctuated from season to season. A report before the start of the 1893-94 season described, “The activity in signing players has not been as marked as in past years, but at the present time there are but few who are holding off for a bonus.”[132] Another report said,

Players who, last season, commanded $50 or $75 for signing with a club have been compelled to come down from their perches a bit, and the few who received a small bonus were very fortunate. As in baseball, the days of high salaries have gone by. The pay of football men the coming season will be regulated according to the patronage.[133]

In other words, players’ pay would remain dependent on gate receipts. But a new method of funding player signings and salaries soon emerged when the Olympics and the Free Wanderers “organized as stock companies on the plan adopted by the local base ball management.”[134] Interested investors could now purchase shares which would be used to aid the funding of club activities.

Not every New England League club embraced professionalism. In January 1891, the Pawtucket Evening Bulletin observed, “There is a Young Men’s Christian Association eleven in Fall River. Why can’t there be one in Pawtucket.”[135] When in September 1893 the Pawtucket YMCA team joined the Rhode Island Football Association, the New England League, and the American Cup tournament, it appears to have been a strictly amateur aggregation, no doubt reflecting the ethics of its sponsor, with no reports detailing offers of signing bonuses or a share of gate receipts.[136]

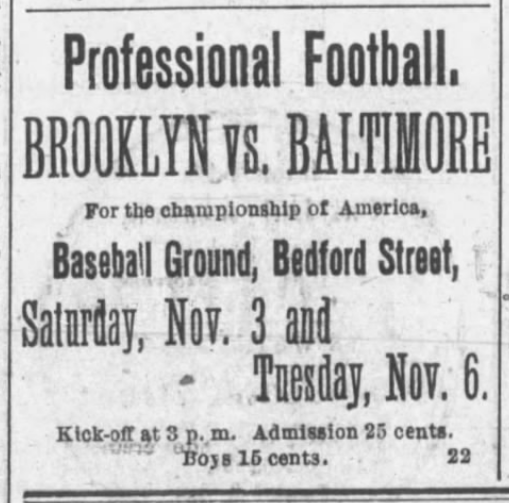

If leading clubs in Fall River and Pawtucket at this time are more precisely described as semiprofessional—players still had jobs to make their living in addition to what they earned on the soccer field—a fully professional inter-city league debuted in the United States in 1894 in the form of the American League of Professional Football Clubs (ALPF), backed by six clubs in baseball’s National League; the American Association of Professional Football (AAPF), which began play before the ALPF, appears to have been semiprofessional.[137] Neither league included clubs in Fall River or Pawtucket, but area players figured prominently in the ALPF’s Brooklyn and Boston teams. Dennis Shea, the heralded Fall River goalkeeper, had been invited to the ALPF’s final organizational meeting, which took place in New York City on August 14, 1894.[138] A little more than a week later, Brooklyn Grooms president Charles Byrne visited Fall River to begin signing players for his soccer team. In addition to signing Shea as the team’s captain, Byrne authorized the goalkeeper to sign fifteen players.[139] He soon had enough of a roster together to field a side against the Rovers on Labor Day—played for a purse of $100—winning 6–3 in front of one thousand spectators.[140] By the end of August, Shea was also signing players for the Boston ALPF team.[141] One player, John Sunderland, reportedly signed with Boston for $80 a month—equivalent to about $2,594 dollars today—plus expenses, although a later report said news of such salary figures was “being accepted with a grain of salt.”[142] Nearly twenty-five players from Fall River and Pawtucket could be found on the Boston and Brooklyn ALPF rosters, a number of which were native-born players.

The loss of so many players understandably raised concerns about the quality of talent remaining available to New England League teams at the start of the 1894–95 season. Even though the ALPF lasted for only sixteen games over two weeks in October 1894, such concerns were deepened when the AFA banned all players who had signed with ALPF and AAPF clubs from competing in the American Cup. It was a curious decision, one motivated by rival organizations encroaching on the AFA’s turf more than an objection to professionalism. Reports make clear that New England League players who were owed “back salaries” by local clubs were paid before the start of the 1894–95 season, with local businessmen chipping in by subscription.[143] Later reports confirm New England League players who had not signed with ALPF clubs also considered themselves professionals and were identified as such.[144] Nevertheless, Fall River and Pawtucket players who had signed with ALPF teams were also banned by the New England League. It is easy to conclude the New England League’s ban was motivated by the desire to stay in the AFA’s good graces so its teams could compete in the American Cup. But one report suggests there was a punitive element to the decision. ALPF players would be “barred in the future, as the absence of the stars has well-nigh destroyed interest in the game for the present.”[145] Players were banned because their absence harmed the prospects of the league, not because they were professionals.

The decline

After a series of matches in Fall River in November 1894 against the Baltimore ALPF team to determine who was champion of the defunct league, the Brooklyns played challenge matches against Fall River and Pawtucket sides and against what remained of the Boston ALPF team.[146] Despite the New England League blacklist, both former ALPF clubs were allowed to enter the Mayor’s Cup. But, once again, harsh winter weather postponed the start of play until April 1895. Attendance was poor when play got underway, and teams failed to show up for scheduled matches. East End eventually dropped out of the tournament. The Daily Globe reported, “The outlook for football in this city is now more discouraging than ever and it is doubtful if the scheduled games will be finished.” Fans were tired of showing up for games only for players not to appear. Players were tired of leaving work to play for nothing. The opening of the baseball season all but insured flagging interest in soccer would be directed elsewhere. Observed the Daily Globe, “[I]t is plainly evident that prospects of raising the sport to its old standard of popularity are anything but bright.”[147]

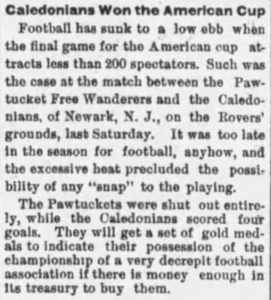

Teams were losing money and in May 1895 play in the Mayor’s Cup and the New England League was abandoned until the next season, with Olympics named the New England League champion.[148] Fewer than two hundred spectators showed up at the Rovers Grounds to see the Free Wanderers lose to Newark Caledonians in the American Cup final, “many of whom were from Pawtucket,” the Daily Globe observed, “a fact which shows conclusively that for a time at least, football is practically dead in this city.”[149] The Daily Evening News concluded, “Football has sunk to a low ebb when the final game for the American cup attracts less than 200 spectators.”[150] For the first time since 1888 the American Cup would be in the possession of a team outside of Fall River or Pawtucket.[151]

The Brooklyn and Boston teams quietly disbanded after the suspension of the Mayor’s Cup. Encouragingly, the New England League’s blacklist preventing former ALPF players from joining local sides was also quietly dropped. Perhaps, given the precarious state of the game in Fall River, it was thought best to do whatever was possible to revive declining interest in the sport.[152] In September 1895 ahead of the start of the new season, the league decided to allocate the former Brooklyn and Boston professionals among its roster of clubs, with the Olympics receiving six players and the Rovers receiving seven.[153] New Bedford was also to receive an allocation but when East End joined the league in their stead it received the players.[154] Soon after the allocation of players was announced, former Brooklyn captain Dennis Shea was elected vice president of the league.[155]

All the New England League clubs entered the 1895–96 American Cup.[156] But attendance for matches in both league and cup play continued to disappoint. While fifteen hundred spectators were on hand at the Dexter Street Grounds on Thanksgiving Day to see Pawtucket’s Free Wanderers and YMCA teams in an American Cup first round replay, only eight hundred were present at the same grounds on Christmas day when the Olympics crushed the Free Wanderers in the next round. When “nearly 500” were on hand to see the Olympics face the Rovers in Fall River in the American Cup semifinal in February 1896, the number was described as “the largest paid attendance of the season,” a dramatic decline from the numbers that would have been expected to attend such an important match in recent seasons.[157] The constant lament in newspaper reports for the better days of only a few years past when thousands would regularly be on hand for matches in Fall River and Pawtucket reflected the precarious state of soccer in the area. A report in January commented on “the almost total collapse of interest in the game of association football” in the New England League’s jurisdiction.[158] The Rovers and East Ends became notorious for not showing up for scheduled games or showing up understrength. The loss of so many top players to the ALPF had grievously affected the level of play the previous season, and that, combined with prolonged bad winter weather, were blows from which the league continued to struggle to recover.

At the end of March 1896, the New England League followed in the footsteps of the Fall River’s Mayor’s Cup and announced it was ending the season early due to the poor financial state of the league and its clubs. The Rovers had stopped appearing for matches and seemed “to be a thing of the past,” East End had disbanded. A report on activity across the border in Rhode Island declared “interest in foot-ball at Pawtucket has ceased.” In order to “prevent running in debt,” the Free Wanderers and YMCA teams canceled all remaining matches, including those for the Mayor’s Cup.[159]

What little money was left in the New England League’s treasury was used to purchase medals for the Olympic players, who were undefeated in all competitions and named the league and Mayor’s Cup champions.[160] So poor were the Olympics’ finances that a subscription had to be taken up to pay for their expenses to the 1895–96 American Cup final in East Newark. Held on April 18, 1896, at Cosmopolitan Park, the Olympics were emphatically defeated 7–2 by Paterson True Blues, the team’s first loss of the season.[161]

A Daily Herald report after the Olympics’ American Cup final loss summarized the poor state of soccer in Fall River and Pawtucket.

The general opinion among the few who have patronized association football this season is that next year no team will be organized, and that the game will be a thing of the past in this city, where three years ago it was the reigning sport. The public began to lose interest in the sport when the first class players were taken for a National league, which proved a failure, their places filled with second raters. The latter failed to show up in acceptable form … The Rovers and the East Ends failed a number of times to put in an appearance at a scheduled game, and the crowd who attended would naturally stay away after being duped several times … If a local team had won the American cup, it would have been necessary to organize next year in order to defend it, but as they lost, it is probable that no team will be formed.[162]

The analysis proved prophetic. In October 1896 the New England League announced it would not organize games for the 1896–97 season. The Rovers’ grounds had been sold and neglected maintenance over the summer meant the East End grounds were not in playable condition. With fans losing interest, and clubs losing money, it was “useless” for the league to continue.[163] The Olympics tried to continue, winning an exhibition game on October 10 against local side Floats, the same day it was reported the New England League would not organize.[164]

Absent a local league, promoters in Fall River wanted the Olympics and the Rovers to play a series of games aimed at determining a select “Fall Rivers” side to enter the 1896–97 American Cup “for the purpose of getting and keeping the cup until the interest in the game was once more aroused.”[165] But the AFA had already organized the 1896–97 American Cup tournament and completed the draw for the first round without the participation of Eastern District clubs. Fall River and Pawtucket, for years the economic engine of the AFA, “had been frozen out.”[166]

With that news the Olympics disbanded, and its players moved on to other clubs such as the Volunteers.[167] Exhibition games played for a prize purse such as the series between Acorns and Floats drew large crowds, including some two thousand people on Thanksgiving Day.[168] But organized league soccer in Fall River and Pawtucket was for now done.

Why the collapse?

Beginning with the founding of East End in 1883, soccer in Fall River quickly developed from one-off challenge games to organized league and tournament play. These developments were mirrored in nearby Rhode Island, particularly in Pawtucket. Multiple competitions were organized to encourage continued development and interest in the game. In joining the AFA’s American Cup tournament, Fall River and Pawtucket made their mark on the national soccer scene, dominating the competition for six seasons. Success in the American Cup soon found Fall River and Pawtucket players competing internationally for all-association and club sides against Canadian teams both at home and abroad. This was soon followed by the inclusion of local players in the Canadian American team that played extensively in Ireland, Scotland, and England, making them the first U.S.-based players to play on another continent. Along the way, professional players began to appear for Fall River and Pawtucket sides. More than two dozen players later signed contracts with teams in one of the first professional inter-city leagues in U.S. soccer history. Meanwhile, efforts were made to organize junior team competitions to develop new talent for senior teams. The development of young players marked Fall River and Pawtucket as an early leader in the development of native-born players, including the first African American players in the United States. For much of this period of development, match attendance numbers were among the largest then recorded for soccer in the U.S.

During this period of development, the reputation of Fall River and Pawtucket as a leading center of soccer in the U.S. soared; it would not be wrong to conclude that the Fall River soccer community particularly saw itself as the preeminent center of the game in the country. And then, within the span of three seasons, organized soccer in Fall River and Pawtucket collapsed.

Contemporary reports place some of the blame for the collapse on the pernicious effects of professionalism.[169] But, as we have seen, professionalism was present in Fall River and Pawtucket from nearly the beginnings of soccer in those cities. The loss of so many “first-class” players to the ALPF, and the resulting ban of those players by the AFA and New England League, undoubtedly affected fan interest. It can be difficult to support your team when your favorite players are playing somewhere else. But, while not as great in number as those who signed with ALPF clubs, the New England League had survived the loss of many of its top players to the Canadian American tour of the U.K. for half of the 1891–92 season. Fierce competition between clubs for top players could drive up the fees players wanted for their services but players could receive only what the market would bear. The question of compensation and its effects on the viability of a league thus becomes as much of a question of soccer administration as of economics.

One recurring problem was both mundane and profound: the weather. Nor’easters are common in Fall River and Pawtucket during the winter months, combining heavy rain, snow and ice storms with already frigid temperatures. As a result, matches were repeatedly postponed, especially so beginning with the 1894–95 season. When they were played, conditions were terrible and made the already poor state of local playing fields worse with little opportunity to improve grounds as the soccer season gave way to baseball and cricket. Attendance at matches necessarily suffered as cold and wet weather and postponed games challenged the interest of even the most committed fans. As the opening of the baseball and cricket season approached, the number of available match days dwindled, which was compounded by the proscription then in place against Sunday games. With clubs having as many four championships to compete for in some seasons—the Bristol Cup, New England League, Mayor’s Cup, and American Cup were all in play for Fall River sides in the 1891–92 and 1892–93 seasons—completing league or tournament schedules in a timely manner, or even at all, was a recurring challenge. Such uncertainty could affect both a club’s commitment to a competition and fan interest in attending matches. Numerous references in newspaper accounts of the day to the summertime being too hot to play soccer as matches stretched into June and July may seem strange to present-day readers but make sense when one remembers uniforms at the time consisted of long wool breeches and wool socks topped with long-sleeve wool shirts.

When considering why soccer collapsed in Fall River and Pawtucket in the middle of the 1890s, perhaps the most important and long-lasting cause was the ongoing effects of the economic depression that followed the Panic of 1893. The economic depression resonated at all levels of the game, from investors in clubs or competitions, to players, semi-professional or amateur, who now had jobs to worry about, to the disposable income available to pay the admission fee for those who wished to see games.

These effects were apparent more generally in the local economy. In August 1894—before players left to join ALPF sides and in reaction to decreased demand as the effects of the economic depression rippled throughout the country—Fall River’s manufacturer’s association ordered “all mills controlled by the association to close their doors” for a month, throwing 23,000 operatives out of work.[170] By the middle of September, some 38,000 workers were on strike and did not return to work until the end of October.[171] How many of these workers were soccer players is unknown. The spinoff from enforced work stoppages and strikes spread beyond owners, managers, and workers to affect local business owners who provided the goods and services of daily life.

Decreased demand was not the only factor in area mill owners leaning on workers to reduce costs. After years of growth, textile manufacturers in northern cities like Fall River now began to face competition from mills in southern states where workers worked longer hours and earned smaller wages, making “the cost of labor in the South about 40 per cent. less than in the North.”[172] By December 1897, the Fall River manufacturers association unanimously voted to further reduce the wages of workers by ten percent.[173] Weekly wages before the reduction for the 28,000 workers in the 75 local mills affected were between $1.50 and $12, about $50 to $403 in today’s value.[174]

With reduced demand and competition from the availability of cheaper products, mills continued to be shut down by owners to reduce production and drive up prices, leaving workers with the equally painful decision between accepting enforced work stoppages and reduced wages or going on strike. In such an economic environment, risking possible injury to play in a match or allocating 15 cents to stand on muddy ground in wind and rain to see a soccer game for which teams may or may not show up with their full side, if at all, then becomes a luxury many could ill afford, just as investing in a soccer club became a luxury. The economic uncertainty that hung over much of the country following the Panic of 1893, particularly in the industrial towns and cities of the Mid-Atlantic states and New England, took a terrible toll on the stability and growth of soccer through the rest of the 1890s and the sport would not begin to truly recover until the beginning of the new century.

Historical currency conversions in this essay were made using the US and UK CPI Inflation Calculators at https://www.officialdata.org/.

Endnotes

[1] “Local,” Fall River Daily Herald, Oct. 14, 1879, 4.

[2] “Foot Ball,” Fall River Daily Evening News, Mar. 27, 1883, 2; “The Game of Football,” Fall River Daily Herald, Jan. 31, 1888, 4; “Sporting Varieties,” Fall River Daily Globe, Apr. 7, 1884, 1. The March 27, 1883 report in the Fall River Daily Evening News says the East Ends were founded “about six weeks ago” and played its first match—an inter-club match between married and single members—”a few weeks ago.” The American Football Association’s annual report for 1887-88 states the East Ends were formed in 1882: “List of Clubs,” Constitution, By-Laws and the Laws of the Game of the American Football Association (New York: Peck & Snyder, no date), 29.

[3] “Cricket Clubs,” Fall River Daily Herald, Apr. 23, 1885, 2.

[4] “Sporting Varieties,” 1; “Personal,” Fall River Daily Evening News, Sep. 6, 1887, 2; “The Vote for Mayor Last Year,” Fall River Daily Evening News, Dec. 9, 1885, 2.

[5] “East End Foot Ball Games,” Fall River Daily Herald, Oct. 22, 1894, 4; “City Briefs,” Fall River Daily Herald, Oct. 27, 1884, 4; “The East Ends,” Fall River Daily Herald, Jun. 11, 1885, 4; “Rovers Lead the World,” Fall River Daily Globe, Jan. 14, 1889, 4.

[6] Football Notes,” Fall River Daily Herald, Nov. 13, 1884, 4; “The Champions of America,” Fall River Daily Herald, Apr. 16, 1888, 4.

[7] “Foot Ball,” Fall River Daily Evening News, Nov. 13, 1884, 2.

[8] “Foot Ball,” Fall River Daily Herald, Mar. 2, 1885, 4.

[9] “Saturday’s Football Games,” Fall River Daily Herald, Jan. 19, 1885, 4.

[10] “Foot Ball,” Fall River Daily Evening News, Mar. 9, 1885, 2.

[11] “Sports in Fall River,” Fall River Daily Herald, April 28, 1885, 4.

[12] “End of the Tournament,” Fall River Daily Globe, May 25, 1885, 4.

[13] “The Field Tournament,” Fall River Daily Herald, Jan. 17, 1885, 4; “A New Tournament,” Fall River Daily Herald, Jan. 8, 1885, 4.

[14] “Fall River’s Leading Sport,” Fall River Daily Herald, Mar. 30, 1885, 4.

[15] Medals in the Field Tournament,” Fall River Daily Globe, Jun. 8, 1885, 1.

[16] “Football Notes,” Fall River Daily Herald, Apr. 3, 1885, 4.

[17] “Foot Ball,” Fall River Daily Evening News, Apr. 13, 1885, 2.

[18] “Football Games,” Fall River Daily Herald, Apr. 13, 1885, 4.

[19] “Football Notice,” Fall River Daily Herald, May 14, 1885, 4; “Football Notes,” Fall River Daily Herald, Apr. 3, 1885, 4; “Big Football Game,” Fall River Daily Herald, Apr. 9, 1894, 7.

[20] “Sporting Notes,” Fall River Daily Globe, Aug. 10, 1885, 4.

[21] “Meeting of Football Delegates,” Fall River Daily Globe, Aug. 13, 1885, 4; “Sporting Notes,” Fall River Daily Globe, Aug. 27, 1885, 4.

[22] “A Disputed Game,” Fall River Daily Herald, Jun. 21, 1886, 4.

[23] “A Disputed Game,” Fall River Daily Herald, Jun. 21, 1886, 4.

[24] “Foot Ball,” Fall River Daily Evening News, May 7, 1888, 2.

[25] “A Football Challenge,” Fall River Daily Herald, Dec. 29, 1886, 4.

[26] “The Rovers Win,” Fall River Daily Evening News, Jan. 14, 1889, 2.

[27] “Local Lines,” Fall River Daily Globe, Apr. 13, 1889, 4.

[28] “Sporting Notes,” Fall River Daily Globe, Oct. 19, 1885, 1.

[29] “Meeting of the Football Association,” Fall River Daily Globe, Oct. 1, 1885, 4; “Meeting of the Football Association,” Fall River Daily Globe, Oct. 14, 1885, 4; “Schedule of Football Games,” Fall River Daily Globe, Oct. 26, 1885, 4.